Facing Disaster with a Smile: The Dick Teague I Knew

First published as “The Teague I Knew” in The Packard Cormorant, 2023. A longer version was published in The Automobile (UK), January 2024. The quote below is from “Horatius at the Bridge” in Lays of Ancient Rome, by Thomas Babington Macaulay.

“And how can man die better than facing fearful odds…”

Franklin, Michigan, April 1971— “Don’t touch it!”

On the garage floor next to a huge Pope-Toledo, a tiny electric compressor was going chuffa-chuffa-chuffa, inflating a tire on this enormous touring car. Richard Arthur Teague, Vice President for Design of American Motors, was on his knees watching it.

“Isn’t it neat?” Dick enthused. “Found it at a hardware store. Look at it go!”

“Yeah, Dick,” I said, “and it’ll be about finished in a week or so.”

I finally tore him away, but I’d no sooner begun asking how he planned to style AMC out of its latest predicament than he lunged into a cardboard box and began hauling out Packard literature.

He held up a bound volume of the ultra-rare Packard Magazine: “Did you ever see one of these before?” He’d rescued the trove from destruction at the East Grand Boulevard factory during Packard’s last days in Detroit.

When tumbrels rolled

“Good Lord, it was awful,” Dick remembered. “There were only a few of us left, they were emptying the factory.

Every hour the tumbrels would roll—you know, like the French Revolution—hauling that aristocratic heritage to the dump. I finally hired a truck, loaded as much of it as I could, and drove it out of there.”

Dick was a Packard stylist from 1951 to the consolidation at South Bend in 1956. His last production effort was the 1957 “Packardbaker,” where he cleverly gave a Studebaker body a family resemblance to the “real” 1956 Packards. Ironically it was Studebaker, which had dragged Packard down, that survived longer.

Most car designers in those days—I don’t know what they do now, click computer keys?—passionately loved the automobile. Most of them could recite automotive history and recall the great names of the industry, from hardboiled executives to racing drivers.

But Dick Teague was unique. He was widely read, brought up to appreciate everything on wheels, devoted to history and restoration. The fabulous 1904 Packard Model L at the Henry Ford Museum, originator of the radiator shape he applied to the last prototypes, was Dick’s car.

His collection ran from his Pope-Toledo to a 1961 Ferrari Berlinetta and the AMX III showcar. He placed his library at the disposal of Automobile Quarterly for our book, Packard; A History of the Motorcar and the Company.

“More rivals than a big city tomcat”

His background wasn’t always cars. A prodigy at five, Dick had played Dixie Duval, the young girl in a low-grade spin-off of Hal Roach’s “Little Rascals.”

A year later he’d lost his right eye in a car accident, and with it his depth perception. (He used to appall us by removing and juggling his glass eye or taping it with a pencil.)

His disability never affected his talent. He grew up sketching cars and airplanes. During the Second World War, ineligible for the draft, he served as a tech artist for Northrop Aviation.

Afterwards Dick joined the industrial design firm E.H. Daniels, who had a contract with a fledgling car company, Kaiser-Frazer.

It seemed a plum of a job, since K-F had barrels of cash and a clean-slate design program, unburdened by prewar “baggage” like the other manufacturers.

The problem was that they hired lots of competing stylists, such as Dutch Darrin and Brooks Stevens, even a company that made car seats. “We had more rivals than a big city tomcat,” Dick remembered.

Then in 1948, General Motors came to L.A. looking for artists, interviewed fifteen of them, and chose Dick Teague. He headed for Detroit, where he contributed to the aircraft-inspired 1949 Oldsmobile.

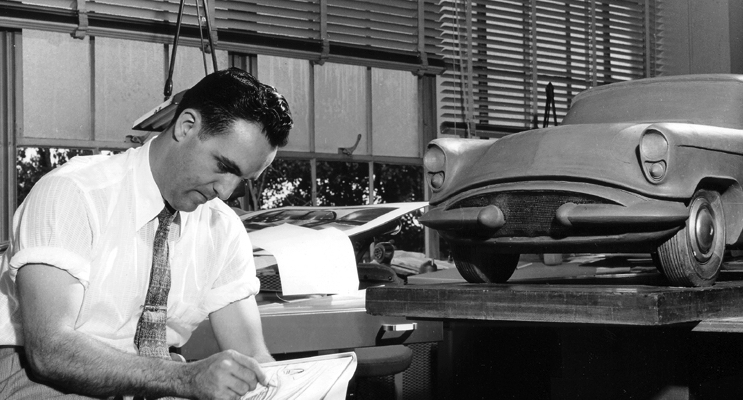

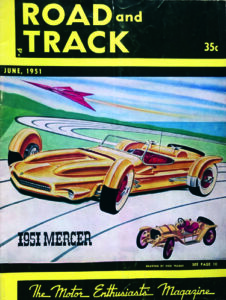

There he met and married Marian, the love of his life, and reeled off the odd freelance project. Many first heard of Dick for the “modern Mercer” he conceived for Road & Track in 1951. It was the best cover R&T had yet published—Dick’s revival of greatest sports car of its era, the T-head Raceabout.

Packard highs and lows

The Packard Cormorant records all he did for Packard, so it isn’t necessary to repeat that here. But no car lover can fail to appreciate the originality of Dick’s mind.

It was he who first reasoned: why does a backlight have to slant back? Why not let it slant forward, eliminating glare, affording rain protection, even sliding down for ventilation? That idea (less the sliding feature) appeared on Dick’s 1953 Balboa showcar, and was later swiped (with the sliding feature) by Lincoln and Mercury.

Many of us know his most famous story, from what he called his “last days in the bunker,” when the “tumbrels rolled” for “Black Bess.”

That was the 1957 Packard prototype (complete with the slant-back rear window). Dick said it was “made with a cold soldering iron and a ball peen hammer…a very spartan mule.”

One day, Engineering Vice President Herb Misch said, “Find it,” and Dick brought it up to a little showroom.

“I can’t do it myself,” Misch said, “so I’m going to make you the executioner. Cut the thing up…it’s all over.” Let Dick himself finish the tale:

“My God, Red, what have you done?”

So I called Rex Lux, an old welder in the studio, who had been around since the cornerstone. There were two or three other cars in the studio, including another black one, a Clipper. I said, “Okay, it’s official, cut the black one up.”

Red had been there since he was a kid and was hanging on by his thumbnails. I came back around 4 p.m. and he was just finishing. The pieces were lying all around like a bomb had gone off.

It was probably the dirtiest trick I ever played but I said: “My God, Red, what have you done? Not this one, man—the one over in the corner!”

The poor guy had to have had a strong heart, because if he didn’t, he would have died right there. His face drained, and when I told him I was just kidding he chased me around the room. You’ve got to have a sense of humor in this business.

With Packard gone, Dick went to Chrysler: “the worst year of my life.” He refused to talk about it—“too painful to remember.” He worked awhile for his old Packard boss Bill Schmidt, then an independent consultant.

In 1960 American Motors design chief Edmund Anderson asked him to come aboard as a stylist, and Dick joyfully signed on with another company headed for the bunker. But this time he put up an extended fight.

“Ruddy ordnance vehicle”

Dick’s first task was to restyle the 1961-63 Rambler American: “You remember, that dumpy thing with the concave body side molding? An English designer had been hired around the same time. ‘My God, Dick,’ he said to me, ‘it looks like a ruddy ordnance vehicle.’ It did, too!”

Dick’s 1964 replacementl was a quantum leap forward—the first Rambler American that could honestly be called good looking.

When Ed Anderson retired, Dick was named to replace him. He started with projects already on the books, like the 1965-67 Marlin, a hasty attempt to ape the Big Three “glassbacks.” But once he could produce ground-up designs, Dick created sleek, flowing shapes, the diametric opposite of conventional Detroit cars.

From a styling standpoint, the 1968 Javelin, his answer to the Mustang and Camaro, bested both of them. Then, cutting a foot off the Javelin wheelbase, he created the AMX, more of a sports car than anything in Detroit other than the Corvette.

When I joined Automobile Quarterly in 1970, Dick was at his apogee. Every time AMC was counted out, he would reach into his bag of talent and produce Salvation.

In 1970 it was the Hornet, a clean-limbed compact, and the Gremlin subcompact, which Dick made by cutting off the Hornet’s back end. It was a desperate tactic, but it worked. The Gremlin sold like nickel hot dogs because with V8 power it wasn’t your typical buzz-box.

“Elephant foreskins”

The 1975 Matador coupe was his purest work. Elegant and smoothly integrated, it looked like 100 mph standing still. I visited him that year driving a new Granada from Ford’s press fleet.

“Good grief,” Dick said, gesturing toward its severe body creases. “Look at all that tortured sheet metal.” Then, pointing to the Matador in his driveway: “Why don’t you get a real car?”

I promised him I’d borrow a Matador as soon as I was back in the graces of our friend John Conde, AMC’s public relations manager.

A few days before, I’d met John at AMC headquarters, where Dick’s newest creation, the Pacer, was on a turntable, observed by a host of component salesmen and other supplicants. I said it was cute.

“What? Just look at that ugly toad,” John fumed, as heads turned. “One door wider than the other…all that glass…doors full of air. I told Teague a hundred times, that little troll won’t do!”

I repeated this to Dick, knowing he’d laugh—he took neither himself nor anyone else too seriously. Actually, he’d been betrayed by the production engineers. Had GM with its resources handled Pacer engineering, “the first wide small car” would have been a greater success.

Nearing retirement in 1985, Teague was getting bored. The government was in the design business big-time now, and controlled everything.

“What are you doing today?” I asked him once. “Government crash tests,” he quipped. “That’s what we’re reduced to. Every day we swing the pendulum at our bumpers, extended out from the body with elephant foreskins.” I cracked up, and he said: “Well, what would you call them?”

“J. Pierpont Teague”

In retirement Dick was celebrated and in demand everywhere. We expected him to be around a long time, to regale us with his memories.

But then from his family, word began to filter that Dick was ill, and that cancer was one bunker from which he wouldn’t emerge, though as usual he’d fight like hell before he gave up.

It made no difference to his enthusiasms. Two weeks before he died, he phoned me to say his last design—a “1992 Packard”—would be on its way for use in The Packard Cormorant. By then his family said Dick was “functional” only twenty minutes a day.

Yet a week after he died his friend Ken Eberts, the great automotive artist, sent it along: “Dick wanted you to have this. He asked me to help finish it, but it is entirely his concept. I think it is his last design.”

Unlike many in his profession, Dick was never proprietorial about his work, quick to credit his colleagues, always ready to lighten up. When worshipful Packard folk would praise his famous 1955-56 “cathedral” taillights, Dick would say:

“Yeah, I was a big hero—J. Pierpont Teague. They raised my salary five dollars, which in those days was a great thing.” (Actually, it was rather more than that, but such was the Teague humor.)

And that’s what I remember most about my dear friend, who died far too young, for he still had so much to give. Everybody who knew Dick loved him. That’s a very large crowd. I’m proud to be a member of it.

More on Packard and its cars

“One Brief Shining Moment: Packard and Its 1929-30 Speedster,” 2023.

“Queen Mary: We Love Our 1950 Packard Eight Club Sedan,” 2022.

“Why Packard Failed,” Part 1 and Part 2, 2022.

“Brooks Stevens: The Seer Who Made Milwaukee Famous,” 2022.

“The Packard Magazine: Ne Plus Ultra of Automotive House Organs,” Part 1 and Part 2, 2021.

“The Packard Adventures of Howard A. ‘Dutch’ Darrin,” 2017.

2 thoughts on “Facing Disaster with a Smile: The Dick Teague I Knew”

I wish I had met Dick Teague; he was a regular at SoCal “old car” functions, but I never had that chance. It’s odd, my first car(s) at 15 were a ’56 Clipper and ’56 Patrician…total cost $75. My high school car was a ’65 Marlin (which I still have) and I own a ’74 Matador coupe (which I have always liked since they were new). I’ve had many confrontations about that “ugly Matador” from others. I don’t get it. In a sense, it was the last vestige of futuristic design before the three box Mercedes look took over. I’ve contemplated channeling the bumpers into thin blades, the only touch I can think of that would improve the design. I still sit and admire its design. Like Vince Geraci, a stylist at AMCM, Teague was very friendly and open, and would readily talk cars. Thanks for the delightful story.

Richard, Great stuff. My parents had a 1954 Conestoga wagon, the first car I remember. I learned to drive on a 1965 Wagoneer with the roll top roof. Then came Volvos. Then came Subarus. I still think of the Studebakers with affection.

–

Doug, Studes to Volvos to Suburus! A steady downhill spiral! RL 😂

Comments are closed.