Kaiser-Frazer and the Making of Automotive History, Part 1

Two kids hooked by the ’54 Kaiser

Joe Ligo of AutoMoments, who produces highly professional YouTube videos on vintage cars, has published an excellent video on the 1954 Kaiser Special he’s admired since high school. No sooner did I start watching than I heard Joe say his liking for the ’54 Kaiser was bolstered by my book: “My ninth grade self thought it was beautiful…. In person, I still think the design is drop-dead gorgeous.”

Well, I too was in the ninth grade when a ’54 Kaiser (on the street, in 1957!) swept me off my feet. It lit a fire that I only put out twenty years later with my first, and perhaps my best, car book.

Well, I too was in the ninth grade when a ’54 Kaiser (on the street, in 1957!) swept me off my feet. It lit a fire that I only put out twenty years later with my first, and perhaps my best, car book.

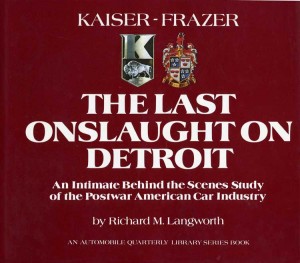

Kaiser-Frazer: Last Onslaught on Detroit (1975, reprinted 1980) was based on dozens of interviews with company engineers, stylists and executives, and packed with rare photos from prototypes to personalities. In 1975 it won both the Antique Automobile Club of America McKean Trophy and the Society of Automotive Historians Cugnot Award. It won, I think, because of the plethora of primary sources. They all were still alive! They had vivid memories, strong opinions, and scores of inside stories.

It was my pleasure to speak on the writing of that book at the Kaiser-Frazer Owners Club 2015 National Meet in Gettysburg. Here is the transcript, inspired by Joe and AutoMoments. By the way, Joe also offers a thoughtful video commentary on the 1954 Kaiser brochure.

Kaiser-Frazer, Part 1: “The Venture”

Gettysburg, 30 July 2015— I am grateful for your invitation, but to tell you the truth I have stumbled over what I might say to you. It’s forty years since Last Onslaught on Detroit was published. The body of historical knowledge about what Edgar F. Kaiser always called “The Venture” has increased considerably. Here in 2015, I am inclined to think that I may well have the least claim of anyone to address the subject with any authority at all. Were it not for the feeling of being among friends, I might turn tail and run. The obvious thing to talk about is the book, how it came to be written, and what we learned that didn’t get into print.

Last Onslaught [Up Until Then] on Detroit was never planned, never outlined in advance. Indeed were it not for two people who are here tonight, and a third who cannot be, it never would have dawned on me that there was a story beyond just another Michigan car company. And the scores of people who wrote that story would not have been heard from.

Artie and the Dragon

Artie Sedmont owned the 1953 Kaiser Dragon that caught my eye in a scruffy filling station near Freehold, New Jersey. I was commuting between Philadelphia, where I was stationed with the Coast Guard, and Staten Island, where my future wife lived. I knew that K-F had built interesting cars. Actually I’d already written an essay about them for my high school English class. Imagine the shock of my teacher, Mr. Quinn, when he received an inscribed copy of Last Onslaught nearly two decades later!

Artie sold me the Dragon. It was odd car, as I learned after joining the Kaiser-Frazer club in 1966. It ran rough and had rust, but the interior was fabulous—Kaiser’s green “bambu vinyl” with green bouclé vinyl inserts. There was a green and white option, but nobody I asked had ever seen all-green before. (Another example has since surfaced.)

Even more oddly, its serial number was for a low-line Kaiser Deluxe: K531-007372. It also bore a small firewall plaque that meant nothing to me at the time, labeled “SPEC-FO” with a four-digit number preceded by a “K.”

We thought we could fix it up, but it threw a rod on the New Jersey Turnpike. Couldn’t afford a rebuilt engine, but for only $250, a friend offered a nice ‘54 Kaiser Manhattan. I repainted it and installed the Dragon’s special interior. I offered the Dragon’s remains free to anyone who would take it away, and a fellow did. Five years later I learned I had committed sacrilege.

Junking a one-off

In Detroit I was interviewing Carleton Spencer, the great fabric and color specialist who created most of the fine Kaiser-Frazer interiors and paints, from the first Frazer Manhattan to the last ’55s. I described the oddball Dragon to Carl. “I know that car!” he said:

We had finished the Dragon run when a late order came in. A customer wanted one like the car in the brochure—ivory with a green top. But he wanted all-green vinyl seats—a combination we didn’t offer. Well, of course we fixed him up. In 1953 we’d build anything you wanted. We pulled a Deluxe out of the body bank and built it to order. The SPEC-FO plaque stood for ‘Special Factory Order.’ You junked a one-of-a-kind automobile!

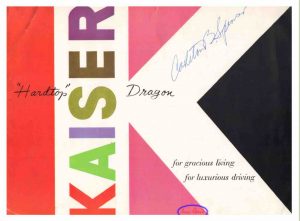

A Dragon flyer was the first thing I received when as a boy I wrote to K-F in Willow Run, Michigan, asking for sales brochures. Years later Carl Spencer signed it, as you see, but there’s always more to a story. Look down at the bottom and you’ll see the printed signature “Paul Rand.” It’s on a number of Kaiser-Frazer brochures.

Paul Rand, born Peretz Rosenbaum (1914-1996), was a prominent graphic designer. He created logos we see every day: UPS, IBM, ABC, Westinghouse. His work is world famous. He taught design at Yale, and in 1974 was inducted into the New York Art Directors Club Hall of Fame. As usual, when shopping for talent, Henry Kaiser’s and Joe Frazer’s tastes were very simple: they were quite easily satisfied with the best of everything.

Bill Tilden

The second key person in the book’s story was Bill Tilden, whom we sadly lost in 2013. One spring evening I was the duty officer at the Coast Guard base when the phone rang: “Sir, there’s a civilian here asking for you. He’s driving the weirdest car I’ve ever seen.”

It was Bill, of course. We clicked from the start. Within a week he hied me off to north Philadelphia, to help strip the attractive, mock lizard skin upholstery out of a rusty old Kaiser. Another bad mistake! We’d junked an ultra-rare 1951 Emerald Dragon. If they built a dozen of those, it was a lot. That made three Kaisers I’d either foolishly scrapped or modified out of recognition. Those three were the last!

After the Coast Guard I drove my ’54 Manhattan with its Dragon seats to Pennsylvania and went to work for the State Health Department in Harrisburg. I eventually sold it to a man from Illinois named Al Mobeck. I don’t know if it survived. Maybe someone knows? It was painted solid Palm Beach Ivory. Its green interior was spectacular.

Bill Miller

I thought then that I was done with Kaiser-Frazer, but suddenly, blocks away from my apartment, I saw this beautiful maroon ‘53 Henry J parked in somebody’s driveway. Meet the third player in the drama: Bill Miller, who became co-founder of Carlisle Events and the famous Carlisle swap meets and auctions.

Bill was a salesman at a local Chevy dealer, so he had a coat and tie. He would show up at my office at the Health Department, introduced as Dr. Miller. I would say we had an urgent appointment. Together we’d toddle off, change clothes, and spend the day junkyarding. We found all sorts of stuff, including a rare ’49 Kaiser Virginian with a canvas roof on top of a hill near Reading. It didn’t run and had no brakes. The junky, Mr. Kettner, in between four-letter words, coasted it down using reverse gear as a braking device. We towed it home, and Bill “tried” to restore it. I do hope he flipped it!

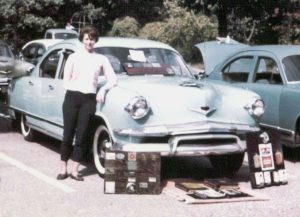

Bill helped get me into my next Kaiser, a 1953 Deluxe painted Cerulean blue. This is a color like the bottom of a swimming pool. It had a sweet manual shift and drove like a song.

When I needed parts he floored me by saying, “You can get anything you need at a Kaiser dealer I know.” What? This was 1968, remember—14 years after the last Kaisers left Toledo.

A Surviving dealer with a brand new Kaiser

Bill introduced me to Frank R. Bobb of Mt. Holly Springs, Pennsylvania. Bobb’s Garage was a ramshackle brick manse which hadn’t been cleaned in a decade, guarded by a hound anchored near Frank’s cuspidor with a chain that could have held the Queen Mary. We walked in and Bill said: “Mr. Bobb, I brought a friend to see your brand new Kaiser.”

With a well-aimed pitooy past the ear of the dozing mutt, Frank led us “out back.” There we beheld a pearl grey ‘53 Manhattan with 3500 miles on the odometer. It was so new the upholstery still squeaked when you sat in it.

That car is still around and maybe some of you have seen it. The paint job was custom. It was presented to Frank for selling the most Kaiser-Frazer cars in his sales area—which in rural Pennsylvania couldn’t have been easy.

More astonishing was Frank’s parts department. He had stuff you wouldn’t believe. How about a 1951 Frazer grille medallion, brand new in the box? Or a chrome and black plastic ’52 Virginian hood ornament? Or block “K” emblems for the ’53 hood or deck? When it came to price, there was no haggling. Frank would look it up in his official price list and charge you full 1953 dealer retail. I think those Frazer medallions cost us all of $3.73 each.

Historical discovery

Mr. Bobb had something else: a complete set of dealer correspondence, sales, service and confidential bulletins, from the time he bought the franchise shortly after the war to the end—which he gave or sold me. Suddenly I was thumbing through hundreds of documents that, sequentially, gave a complete picture, from a dealer’s standpoint, of the rise and fall of Kaiser-Frazer and its successor, Kaiser-Willys.

This stirred my historical instincts. By then I was editor of the Kaiser-Frazer club quarterly, which had arrived on my doorstep unsolicited, from dear Tom Wilson in Michigan, the previous editor, who just got tired of it. The club told me to go ahead and produce something, so I did. It was embarrassingly amateurish, but everybody was very kind.

Fired up, I wrote to our chief honorary member, Joseph W. Frazer, and asked for an interview. What the heck, right? He floored me when he said sure—come out and see him at “High Tide,” his French-style chateau on the coast in Newport, Rhode Island. Unique among Detroit auto executives, he had commuted weekly to and from Newport. Years later, I named our house in the Bahamas “High Tide” in Joe’s memory.

Off we went, Bill Tilden and me, to record for the club magazine the first words Frazer had said publicly about Kaiser-Frazer since he left the board of directors in 1953. We published the transcript in the summer 1969 issue, as I remember. I don’t have it. All my print archives were destroyed in a fire that burned my antique barns in 2003.

Joe Frazer and Hickman Price

Mr. Frazer’s nephew, Hickman Price, was present for the interview. Joe was widowed now, living in a small wing of this beautiful house. Hickman was redecorating the rest. Bill and I gathered that he was the old man’s watchful protector. We drank Tennessee bourbon and branch water, and they both loosened up.

Mr. Frazer was very careful not to criticize anybody, but it was clear that he’d been heartbroken over the failure of the company. The two things he was most proud of said a lot about him. The first was that at peak, they had 20,000 people working. The second was that 100,000 cars bore his name. He also said something about the auto industry I will never forget: “There’s so much money going out the window every day in this business, that if you’re not careful you’ll lose your shirt.” That, of course, is exactly what happened to Kaiser-Frazer.

As we left, Hickman Price made me an offer: “If you ever decide to write a book, come back and see me. I will tell you a thing or two about that benighted company nobody else will.” He proved to be as good as his word.

“You’re going to pay me to write about cars?!”

Possessed now of just enough knowledge to be cocky, I wrote an article about Kaiser-Frazer and sent it unsolicited to Automobile Quarterly in New York City. Not only did they buy it; they asked if I’d like to come to work as associate editor. I said I’d grown up in New York and had vowed never to return, I was a country boy. “But wait—did you say you’re going to pay me to write about cars?” The decision was inevitable.

What luck! Automobile Quarterly then, 1970-75, was in its golden age. Its editors were twin geniuses, Don Vorderman and Beverly Rae Kimes. They taught me things I would always remember and use to my benefit. Don reminded me about brevity: “A bore is somebody who tells everything.” Beverly’s advice was more personal, and important: “Never fail at anything.”

Automobile Quarterly had great art directors and a range of writers, artists and photographers. From Ken Purdy to Karl Ludvigsen, Peter Helck to Walter Gotschke they were the best in the game. They actually paid me to hang around and learn from these people.

I was hired to edit a series of books, the first of which was The American Car Since 1775. The last was the multi-author Packard: A History of the Motorcar and the Company. Along the way I asked shyly if I might write a book about Kaiser–Frazer.

“It won’t sell,” the boss said. “But go ahead. Take as long as you like.” We were all astonished when it sold 20,000 copies in two printings.

2 thoughts on “Kaiser-Frazer and the Making of Automotive History, Part 1”

A most enjoyable read on this overlooked marque! I’ll watch for Part II!

Thank you for linking to my blog post about Carleton Spencer. (Any quotes from your book in the blog post without attribution were unintentional!)

Love this history of a great car company.

Comments are closed.