Why Studebaker Failed: In the End, It is Always Management

Why did Studebaker go out of business? I have your book Studebaker 1946-1966, originally published as Studebaker: The Postwar Years. I worked for the old company at the end in Hamilton, Ontario. Your book brought back memories of many old Studebaker hands. Stylists Bob Doehler and Bob Andrews were good friends about my age.

Why did Studebaker go out of business? I have your book Studebaker 1946-1966, originally published as Studebaker: The Postwar Years. I worked for the old company at the end in Hamilton, Ontario. Your book brought back memories of many old Studebaker hands. Stylists Bob Doehler and Bob Andrews were good friends about my age.

I am looking forward to the last chapter discussing how Studebaker went wrong, especially since I also have theories. It would fun to compare notes. I often quote from your book: “For many years, Raymond Loewy Associates would be the only thing standing between Studebaker and dull mediocrity.”

Like you I owned a 1962 Gran Turismo Hawk, a surprisingly impressive car. Drove it back and forth to Hamilton when we were working on the last 1966 production Studebakers. I put a ’53 Starliner decklid on it and ’54 Starliner wheel covers; I thought each addition was an improvement. —B.M.

Studebaker remembered

Thanks for the kind words. My GT Hawk was one of the best cars I ever owned: fast yet easy on gas, stylish, fun to drive. It leaked oil and the famous “flexible frame” was a little creaky, but it was a satisfying car, if overly susceptible to the dreaded tinworm.

At the end of my book is a list of what Studebaker did wrong, beginning with chairman Paul Hoffman accepting every union demand after World War II. James Nance, the last president of Packard, which purchased Studebaker in 1954, had it right. “The trouble with Studebaker was that they wouldn’t take a strike. Everybody else took strikes after the war and reasonable compromises were reached on wages and benefits. Studebaker didn’t, and they never caught up.”

What Packard didn’t know when they bought Studebaker they learned to their horror when accountants finally got into the books. Studebaker’s break-even point by the mid-Fifties was 50,000 or more cars higher than their best-ever annual volume. A Studebaker designer told me he once priced the 1953 Starliner using General Motors costings. He found that GM could have sold the identical car for $300 less (which was a lot more then than it is now).

Packard indeed had its own problems. But Studebaker dragged Packard down with it, making it impossible for Nance to find the finances to bankroll an all-new 1957 line that might have allowed Studebaker-Packard to go on longer than it did.

The greatness of Raymond Loewy

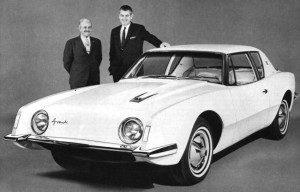

And yes, Raymond Loewy led the teams that created the 1953 Starliner and 1963 Avanti. They were the key to the cars being as distinctive as they were. Loewy had a keen eye for talent. He hired and directed fine designers, such as Bob Bourke (Starliner) and Bob Andrews, John Epstein and Tom Kellogg (Avanti). The Avanti was impressive, but perhaps not the right product for Studebaker. Otto Klausmeyer, a longtime and outstanding engineer, told me he regarded it as “our first a duck-back, droop-snoot sport car.”

Studebaker’s sales and marketing people blunted those good designs by inept planning and promotion. In 1953, for example, they built a surfeit of sedan models, finding to their shock that people mainly wanted the beautiful Starliner hardtops and Starlight coupes. Their production mix was the exact opposite of what the public desired.

Brooks Stevens’ life support

But Studebaker’s styling was consistently good. Trying to save the rump company in the Sixties, President Sherwood Egbert hired Brooks Stevens, who deftly facelifted the Lark and Hawk, and came up with novel ideas like the sliding-roof Wagonaire station wagon—but these were all reskins of the 1950s models. Stevens and Loewy then offered exciting ideas for all-new designs for 1966 and beyond.

But by then it was too late. Studebaker shut down its main factory in South Bend, Indiana, in December 1963, and the Hamilton Ontario plant closed after building the last 1965-66 models. But no—Studebaker didn’t have to fail. George Mason of Nash saw the future before anyone else. He tried to build a conglomerate of independents—Studebaker, Packard, Nash, Hudson—in the 1940s. Nobody else was listening. It was probably the only way to stave off death for those companies. After World War II, economies of scale worked greatly in favor of the big automakers. But hindsight is always cheap. And far too easily indulged.

9 thoughts on “Why Studebaker Failed: In the End, It is Always Management”

Pop owned a ’53 Studebaker with “3-on-a-tree” and the “hill-holder” feature, where you could take your left foot off the clutch after setting it, as he described it to me. Genius!

I was Studebaker “nut.” I owned almost every model since the ’49 “bullet nose” except the Avanti. Most saw major modifications while in my care. But my two favorites were my ’56 Golden Hawk to which I installed a blower, and the ’64 GT Hawk with a 302 and blower. The ’56 Golden Hawk amassed over 200K miles before I finally sold it. Even the Wagons and convertibles were great autos but prone to rattles! Some frame modifications helped. And I never had problems with the Borg-Warner tranny pulling a 16-foot boat and trailer. And you are correct, neither the sales team nor management had any idea of how to market these stupendous cars.

–

Thanks. My experience also. Studebaker designer Bob Bourke (’53 Starliner) referred to the 120-inch wheelbase as “the rubber frame.”—RML

Soon after I obtained my driver’s license I asked my father to buy a Hawk. The standard paint job was white below black above. The dealer reversed this for us. Great car: electric overdrive, Hill-Holder, but the front end did not recover well after tight turns. It had a tachometer—that made all the difference for a kid.

Amazingly when Studebaker was developing its V8 in the early Fifties Cadillac actually let its engineers tour Cadillac’s production facilities. The Studebaker engine was technically not bad and had a reputation for reliability, but was small bulky and heavy with limited room for development—which was also greatly, perhaps preeminently, restricted by lack of investment capital. In the end, if it wasn’t for the war Studebaker would have failed much earlier. On the other hand, Studies were unusually attractive. Gotta love the Avanti.

–

True observations. The V8 was a big plus, and did evolve from 232 to 302 cubic inches, but they had to resort to supercharging to get more out of it. In the end, though, it was their enormous overhead that made it impossible to break even. —RML

I never owned a Studebaker. I was barely out if high school when they were gone. But I thought they were the class of the road in the early Fifties and had my heart set on a Hawk about the time they closed. While they were built awhile longer in Hamilton Ontario, they really never had a dealer network in Canada. They had beautiful half-tons that should have sold as well as GM or Ford, but there were few dealers that handled the Studebaker line. I’m told that was true in the States as well. That should have been addressed between 1933 and 1950. It’s easy to look back and say they should have done this or that, and in this case I’m sure there were a multitude of bad decisions, but this company could have been prominent to this day with its styling and engineering. If I had the money to bankroll it, I’d buy everything that’s left and revive it. It’s the doing that counts, not the money. Great name, great waste.

Indeed so. I only sold mine because it was not fun to drive and I needed room for a Packard! Don Vorderman told me: “You are not old enough to have experienced the impact it had on everybody who was into cars. How gorgeous! How un-American!” See: https://richardlangworth.com/don-vorderman.

IMO Bourke’s Starliner is a timeless design that is as beautiful now as it was in 1953, I was six years old when this car was introduced and I was already a “Gear Head”. When I first saw it I thought it was the most beautiful car I had ever seen. Nothing in the 67 years that have passed since then has changed my mind about that car. The one you owned is my favorite color combination for the Starliner. Bourke’s fine design gave Stevens “good bones” with which to work in creating the Gran Turismo Hawk for 1962-1964.

You should have been a poet, Randy.

The sun was slowly setting as long shadows lengthened that hot summer afternoon in rural Bradford, Illinois. Fortune found us standing in front of that old red barn, miles from nowhere. “Have you ever seen a Studebaker Avanti?” she asked as the barn door swung open. In the shadows were no fewer than eight of them—each Avanti a different color—gleamng in sun’s golden shimmer. The owner, Leslie T. Welsh, owner of the Studebaker Worthington Company, had died several years before. He was the Arthur Anderson executive charged with breaking up Studebaker. He bought the heart and soul of the company, its engine division, and built an empire. She asked me if i wanted to drive one of the cars. I chose the red one. She smiled. I smiled too.

Comments are closed.