Brooks Stevens: The Seer Who Made Milwaukee Famous

Purple prose (or maybe just mauve?)

Awhile back Hemmings Motor News reposted my article on Brooks Stevens, with a gratuitous opinion: “Perhaps Langworth’s tendency toward purple prose in this profile of Brooks Stevens in Special Interest Autos #71, October 1982, is appropriate, given the picture he paints of the legendary designer.” Nice to be remembered, but, er, Hemmings paid only for first rights and is therefore in copyright violation.

An old editor at SIA wrote: “Nothing purple—it reads like an essay in The New Yorker.” (Ah, if only Hemmings paid New Yorker rates!) Another colleague wrote: “Not purple, maybe faint mauve.” A third: “Ugh, I can’t read it. The prose is too purple for me. They really think the Excalibur J can run with a Jaguar XK120?” But Tony Stevens wrote: “As the current owner of the first Excalibur J, I can attest that it can run competitively with an XK120. Right, Tony! The XK120 was a great car—but the youngsters have swallowed too much purple prose about it.

Herewith I republish my purple-mauve piece on my late friend Brooks Stevens. Readers may judge for themselves.

“The judgment of the historian”

“You’ll have to resolve the conflict between Dutch Darrin and Kip Stevens,” I was told after being assigned my first automotive article assignment, on Kaiser-Frazer, in 1970. The origins of the landmark 1951 Kaiser were at the time still unclear. Both Darrin and Stevens claimed it. (See “Kaiser Capers.”) Neither was complimentary in describing the efforts of the other. “It might be best not to press the matter,” a friend warned. The publisher disagreed: “Hear both sides and make the judgment of the historian.”

I didn’t know I was a historian! But I wrote to Stevens at his studio near Milwaukee and said in effect, “Tell me everything you remember about the 1951 Kaiser.”

By return mail came a large white folder with gilt lettering, containing a thick pile of photographs and a long, detailed letter documenting Brooks “Kip” Stevens’ role as a design consultant to Kaiser-Frazer. Within a year we’d met, and our friendship withstood the “judgment of the historian,” which appeared in Last Onslaught on Detroit in 1975. (For used copies search on bookfinder.com.)

The judgment did not satisfy Kip, and in turn produced another white and gilt folder with further documentation. On this subject it would be accurate to say that we had differences but not misunderstandings. Cordiality never suffered, for Stevens was a master of cordiality.

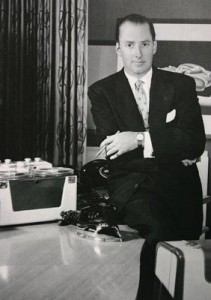

Stevens as I knew him

He was a tall, good looking man who belied his age, whose appearance and demeanor reflected what Cole Porter called High Society. For Stevens there was only one way to fly to Paris: Concorde. And one way to get to England: first class on the QE2. His personal tastes reflected similar standards, producing an aura of refined elegance. He took pains about everything. Meeting him, people were impressed but never overawed, because he was so natural, so full of courtesy and fun.

It was not hard to gain Kip’s acquaintance, whether you were a mechanic in overalls or the President of General Motors. Along with an inborn civility and an interest in others went an all-encompassing love for cars, an encyclopedic knowledge, and a streak of nihilism.

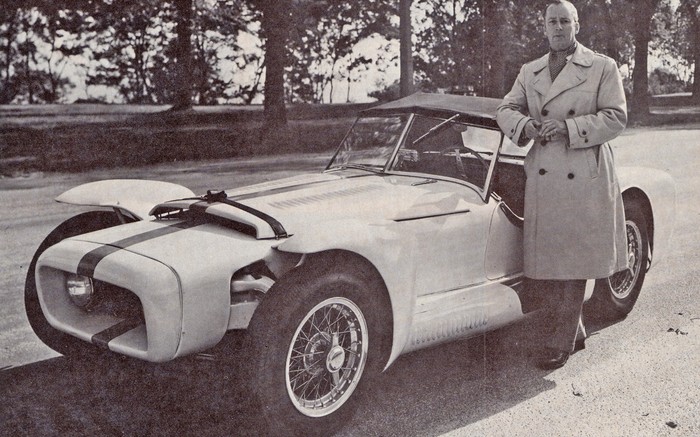

Stevens once invited my friend Bill Tilden to Wisconsin to drive his Henry J-based sports car, the Excalibur J, at Elkhart Lake. Brooks himself drove there in his personal Excalibur. This produced a helicopter-assisted roadblock of the rambunctious designer. It seemed he had violated most Wisconsin road ordinances plus several they hadn’t thought of yet.

Picture Brooks, trailing a silk scarf, driving a very loud open sports car with what the British call “assurance.” Picture next an army of gendarmerie, including aircraft. Failing to catch him in their cruisers, they block the road ahead. Now picture the nearest constable (seven feet tall as they all are). Jerking his thumb at the Excalibur’s sartorially splendid driver, he shouts: YOU—OUT! Kip paid his fine. It was substantial.

A truly lovely man

He had vast generosity, which did not always function in his favor. One press night at the New York Automobile Show, Kip arrived at René and Maurice Dreyfus’ famous automotive watering hole, “Le Chanteclair,” with a large retinue of admirers. The brothers Dreyfus were hardpressed to seat such a large assembly. They eventually did, at a long table with Brooks as centerpiece. Here he held forth for three hours to his impromptu court.

Le Chanteclair was never the place for a cheap meal. The bill came, for what I recall was uncomfortably close to a thousand 1974 dollars. Brooks quietly laid down his American Express card. Those who had no intention of socking him with that tab surreptitiously handed him cash, but a good half the company didn’t bother. There was no sign that our host was in the least disappointed: the measure of a man who spared no expense for the pleasure of an evening among friends, provided your description of “friends” is fairly elastic.

Stevens triumphs

I once stole a line from Schlitz and called Brooks, to his great delight, “The Seer Who Made Milwaukee Famous.” He was one of the ten charter Fellows of the Industrial Design Society of America. To the automotive trade he brought impeccable credentials. Ultimately he would contribute designs to over 40 makes of car. One of his earliest associations was with Willys-Overland, during and after World War II. He conceived of Willys’ most interesting products: the the first all-steel station wagon (1946); and the 1948-51 Jeepster, the world’s last production touring car.

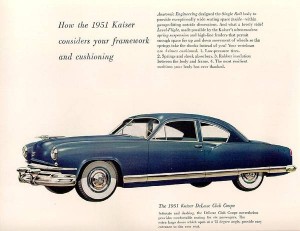

A contributor to Kaiser-Frazer from almost the outset of that venture, Brooks proposed the first practical facelifts for the plug-ugly 1947-48 models, including wagons and hardtops, which they desperately needed but rejected.

Management didn’t take his advice, but assigned him a design competition for the new-generation 1951 Kaiser. It is the consensus today that the basic shape selected was Darrin’s, but the contest was not winner-take-all (see Kaiser photo above). Kip was simultaneously busy on a score of accounts in a half dozen countries, with corporations like Allis-Chalmers, Miller Beer, Briggs & Stratton, Evinrude, Lawn-Boy, 3M, Outboard Marine Aviation, Sears Roebuck, and Club Xanadu in Costa Rica. At the time of the Kaiser styling contest he was involved with Alfa Romeo on the 6C 2500. Darrin had only the Kaiser project on his plate. Had it been a one-on-one contest, things might have been different.

Kaiser and beyond

And many of his contributions were used on Kaiser products. After the Kaisers bought Willys in 1953, Stevens designed the Jeep Wagoneer, a shape that lasted 30 years. He always referred to this and his other styling projects in the plural: “we” did this or that. He simply wanted to make it clear that Brooks Stevens Associates was not a one-man company.

Kip also did his own thing on a Kaiser chassis. While Darrin was placing a pretty fiberglass body over a stock Henry J chassis to create the Kaiser-Darrin, Stevens moved in the opposite direction with the Excalibur J. This was a highly modified, dual purpose, road-and-track sports car. It could pace the vaunted Jaguar XK120, and often did in competition.

In the late Fifties, Stevens created the Excalibur-Valkyrie-Scimitar design exercise, which showed what could be done with aluminum. In the 1960s he reskinned the Aero-Willys for Willys-Overland do Brasil. This facelift persuaded Studebaker President Sherwood Egbert to let him modernize the aging “Loewy coupes.” The result was the sinfully beautiful Gran Tursimo Hawk of 1962-64.

Next Kip applied crisp, modern styling to the dowdy Studebaker Lark, giving it an extra lease on life. He produced the first sliding-roof station wagon in the Wagonaire, and his Studebaker prototypes for a new generation of cars were things of breathtaking beauty. (See “Why Studebaker Failed.”)

Faithful but unfortunate

Unhappily, most of his automotive efforts were for dead or dying companies. Had Kip worked for say, Chrysler, they would be more famous. Still, he managed to cap his career with an unequivocal success. This was the Excalibur line of “modern classics” based on a successive series of Mercedes-Benz commencing with the immortal SSK. Among “replicars” the Excalibur was the best selling, best engineered, and most carefully built.

Automobiles were but one facet of a half-century career, but they were his first love. He established the Brooks Stevens Automotive Museum, small and select, including some of the finest: the Packard Twin Six, Duesenberg Indy racer, Brescia Bugatti, Mercedes-Benz 500K and 540K, Cord L29 and 812, Marmon V-12. Its frontispiece was a staggeringly beautiful 1939 Alfa Romeo 8C 2900B, the world’s fastest prewar sports car. He added many of his own personal designs, like the Jeepster and Brazilian Willys, and the Alfa 6C 2500.

Clifford Brooks Stevens (1911-1995)

Kip did not come in for the universal plaudits he deserved. Too often, casual observers saw only him as hopeless exponent of chrome and tailfins. This is very shortsighted, for it fails to take the full measure of the man.

He was one of the supporting pillars of the automotive community: manufacturers and collectors. His whimsical, brilliant, imaginative, formal and radical designs were truly unique. His non-automotive work served America’s great corporations. Many of his designs, still around today, gained international renown.

He was as well a great companion, not at all self-centered (rare among designers). Always he drew out the best in his friends—car nuts, fellow stylists, lowly automotive writers. No one escaped his attraction. Everyone became proud and delighted to have their work encouraged by a man of such distinction.

There are many ways to measure wealth, but Kip Stevens banked his greatest treasure in the hearts of his friends. We cherish his memory.

Further reading

“The Greatness of Alex Tremulis,” Part 2: Tucker to Kaiser-Frazer,” 2020

“Kaiser-Frazer and the Making of Automotive History,” first of two parts, 2019

“All the Luck: Howard A. ‘Dutch’ Darrin,” first of three parts, 2017

“Joe Frazer, Father of the Jeep,” first of three parts, 2011

2 thoughts on “Brooks Stevens: The Seer Who Made Milwaukee Famous”

I have been searching for the history of Brooks Stevens, and ended up here because it overlaps with a weird artifact I own. I have a large beautiful buffalo hood ornament. I think it might be Kaiser, but I can’t find much. I see you have written extensively on Kaiser-Frazer. Are you familiar with it? Maybe it was an aftermarket item? I have wondered for years, can you point me anywhere to further research. My dream ending is that Brooks designed it, lol. Thanks for any help.

–

Al, yes, there were several “buffalo” style aftermarket hood ornaments for Kaiser cars. The first models had none, and there was great clamor for them. The company itself eventually made its own: a kind of “sail” for the Kaiser and helmed knight for the Frazer. Though Henry Kaiser chose the buffalo for his hood badge, all the buffalo mascots were by outside suppliers. I am fairly sure none were designed by Brooks Stevens. His own proposals for new models did not include any.—RML

Like I have said before, I really enjoy your car stories and marvel at your in depth knowledge of that industry.

Comments are closed.