“One Brief Shining Moment”: Packard’s 1929-30 Speedster

My piece on the Packard Speedster appeared in Collectible Automobile, February 2022. Order a copy for their superb color photography. However, car magazines rarely want endnotes, and since this is a slightly more academic venue, my endnotes (along with many hyperlinks) are included for reference and further reading. RML

*****

“For those who love speed coupled with utility features of general motoring, Packard builds its Speedsters. Perhaps it is the inherent flow of speed joined to the swift grace of smooth design that suggests these interesting body treatments. But Speedsters they all are, from test car to Runabout. For those who thrill to the maximum speed of an open car on an open road.”1

Speedster origins

The term “Speedster” may have originated “when someone knocked the tonneau body off a car and installed something racier,” wrote Packard connoisseur Bob Turnquist. “Most often, Speedsters were sporty, relatively light cars with a large gas tank. To many, such styles were just high fashion. To others, they were like an Indy racer primed for street use. Indianapolis was a direct inspiration.”2

Many consider Packard’s 1929-30 Speedster an anomaly from a company known for luxurious transportation and understated elegance. Packard “catered to the ballroom and country club set,” wrote Ronald Sieber. “Although enterprising racers would use its engines in specials that won events on both road and river, and would perform daring aerial maneuvers in Packard-powered aircraft both in war and in peacetime, Packard itself shunned racing and performance-oriented events.”3

Enter the Colonel

But Packard was not totally uninterested in high performance. In 1916, for example, the company built two impressive racing cars for the racing driver Ralph DePalma: the “299 Special,” featuring its new, 424 cubic inch Twin-Six car engine; and the “905 Special,” powered by a Packard Liberty aircraft engine.4 Packard Liberties also powered racing boats, including Gar Wood’s “Miss America 2,” winner of the 1921 Harmsworth Trophy. Earlier, the Liberty had distinguished itself in wartime aircraft. By 1930, when Packard created a Diesel radial aircraft engine, it proclaimed itself “Supreme on Air, Land and Water.”

The visionary behind much of this innovation was Colonel Jesse Gurney Vincent, head of engineering from 1912 to 1946, father of the Packard Speedster. By 1927 Vincent had completed Packard’s million-dollar Proving Grounds at Utica, Michigan, a 2 1/2-mile banked oval similar in size to Indianapolis.

“The Colonel relished speed,” wrote Morgan Yost, but “the roads of Michigan [were] crowded, twisted—and patrolled. With Utica…Jesse Vincent could move as fast as he wanted.” At a 1928 dealer convention, he circled the Proving Grounds in a Rollston-bodied sedan at 85 mph. “That was incentive enough for a faster Packard, to satisfy the Colonel, to use the track for publicity purposes and to take advantage of the advertising value of speed.”5

“Les camions les plus rapides”

In late 1925, Vincent admired a custom speedster phaeton designed by Raymond H. Dietrich of LeBaron, the Manhattan coachbuilders. Six inches lower, four inches narrower than standard, riding 21-inch wheels, with a stretched hood and raked-back windshield, it looked like an antelope next to the standard production horses.6 LeBaron built two and sold them for $10,500 each—$180,000 in modern dollars. These striking phaetons astonished the public and the company. On Mahogany Row in Detroit, Packard’s conservative managers liked it. Perceiving that they had an itch, the Colonel yearned to scratch it.

Vincent was further impressed by a fast ride in a sporty Bugatti during the 1926 Paris Auto Show.7 His driver was Ettore Bugatti himself. The eccentric Frenchman was said to have remarked that W.O. Bentley built “les camions les plus rapides” [the fastest trucks]. It is not on record what Le Patron thought of Packard Speedsters, which were not as athletic as Bugattis.

My dear friend the late Bob Valpey readily admitted this. When I asked him if he intended to run his 734 Speedster roadster on the Lime Rock, Connecticut road course, this veteran vintage racing driver quipped: “I’d be quicker in a dump truck.” At the Proving Grounds banked oval, of course, Col. Vincent could go as fast as the machinery allowed.

During 1927, Vincent went to work. He built four Speedster prototypes, three of which were “test mules.” One was supercharged, but Packard’s conservative management balked at radical modifications, and three were disposed of by December. One was bought by young Briggs Cunningham, after driving it around the Proving Grounds at over 100 mph, Cunningham used it as a daily driver and project car while studying engineering at Yale. It may be seen today at the Revs Institute in Naples, Florida.8

The Vincent Speedster, 1928

Faced with the need to use stock Packard components, Vincent selected his second prototype for further development. He built it the way every hot-rodder would decades later, stuffing the biggest engine into the smallest chassis. The latter was from a Packard 443, riding a 126.5-inch wheelbase. (Some say it was a 626, but its crankhole position and eight-lug wheels suggest 443.) The engine was the nine-main-bearing 385 cid Super Eight with 106 bhp in stock form.

Designed for speed, Vincent’s special had an aluminum body and lacked road equipment—no lights, windshield, fenders or bumpers. Its twin bucket seats were staggered, the passenger’s mounted slightly farther back to give the driver more elbow room when wheeling this brute around the Proving Grounds. And wheel it did, according to Charles A. Lindbergh.

In 1928 the famous aviator visited the Proving Grounds to see the new Packard Diesel aircraft engine, and Vincent offered him a few laps with his toy. “I drove the car several times around the track, at a little over 100 miles an hour, if my memory is correct,” Lindbergh wrote. “I believe the average was 109 mph, and that the car had averaged about 128 mph with its regular driver; but I am vague on these figures.”9

Reborn and Recreated

Jesse Vincent’s Speedster remained at the Proving Grounds for many years and then disappeared. Its body shell was found in the 1970s by Packard collectors Dale and Don Lyons. Along with A.J. “Jim” Balfour, they rebuilt the car with “donor” Packard parts. By the 1990s, it was seen at Packard Club events. It is now displayed at America’s Packard Museum in Dayton, Ohio. Jim Balfour wrote about it in The Packard Cormorant #52 (Autumn 1988).

Then in 2016, Jerry Miscevich of Burbank, California, built a perfect reproduction. “I saw its pictures in the 1978 Automobile Quarterly Packard book,” Jerry told Jay Leno, “and I just said ‘wow—I can’t believe they made something like that’….It just wouldn’t leave me alone.”10

Working only from photos, Miscevich formed the body (steel not aluminum in this case) over a wood frame, the engine bored out and tuned to deliver 120-125 bhp. Every component matched the original, including the Bijur lubrication system, Detroit Lubricator updraft carburetor, three-speed gearbox, 16-inch mechanical brakes and staggered seating. This exacting recreation can be enjoyed in a video with Jay and Jerry on “Jay Leno’s Garage” via YouTube.11

Sixth Series 626: first production Speedster, 1929

With Packard riding high on seemingly-limitless 1920s prosperity, a production variant of the Vincent Speedster was conceivable. Packard chief body designer Vincent D. Kaptur was entrusted with the first production model. He was assisted by a bright new designer named Werner Gubitz, of whom more anon.

The cars were introduced on the 1929 626 chassis in August 1928, most with roadster or phaeton bodies. A few sedans were also built. Racing driver Tommy Milton drove a sedan from Miami to Los Angeles averaging 50 mph, which was pretty impressive given the roads of those days.

The specification followed Vincent’s practice of a big engine in a small chassis. Power was from the 385 cid Eight, with high-lift camshaft and high compression head, which raised horsepower to 130. Unique to the Speedster was a vacuum booster pump. The rear axle ratios were 4.00 or 3.31 instead of the standard 4.38 and 4.07. High gearing was uncommon when few roads allowed rapid motoring. When they did, though, the Speedster owner could “open her up,” press a floor pedal, and enjoy what Ned Jordan called “the roar of the cut-out.”

At a glance, the 626 Speedster looked like an ordinary Packard, with a longer hood and shorter deck, crafted in the company’s new custom body shop. The roadster lost 14 inches behind the front seat to fit the 126.5-inch chassis; the phaeton was more conventional. The price for either was $5000 ($86,000 in today’s money), a hefty sum in 1929.

The little-known 626

That this Speedster even existed was uncommon knowledge, because Packard did no specific advertising. As a result, production was trifling. Estimates run from fewer than 50 to a high of 70 for all body styles; one source says only 24. Alas only three 626 Speedsters are known to exist, and for many years the Henry Ford Museum’s roadster was thought to be the only survivor.

The Museum’s car, the gift of Montgomery Young, represents one of the most enduringly attractive, finely finished and luxurious Packards of the 1920s. The original owner, Emil Fikar, Jr. of Berwin, Illinois, insisted it be capable of 100 mph. After personally satisfying himself that it was, he paid Chicago’s Bruesce Motor Sales $5260 in October 1928. The invoice listed only two options: chrome plated wire wheels ($250), and goddess of speed mascot ($10). Packard declined to supply fripperies like sidemounts or windwings: “As minimum head resistance is essential for maximum speed, no specifications are accepted for Deluxe equipment for these special cars.”12

Designing the ultimate Speedster

Despite thin sales of the 626, Packard decided to expand the line for 1930, producing the grandest Speedsters yet. A significant departure, the 734 was longer and more powerful, with long-legged gearing mated to a four-speed gearbox. The engine was the 385, specially cast for Speedsters with angled ports allowing hemispherical combustion chambers. Significantly modified for freer breathing, the 385 carried separate intake and exhaust manifolds, the latter finned. There was a special two-throat carburetor, vacuum pump and pedal-controlled exhaust cut-out. It developed 125 bhp, but an optional 6:1 compression head produced 145 and a whopping 290 lbs-ft of torque at only 1600 rpm.

Though Packard recommended the lower-compression head and 4.00:1 gear ratio, most open models were ordered with high-compression and 3.33:1 gearing. This ensured that your Speedster would top 100 mph—and people spending Speedster money were inclined to want that. There was also a 4.67:1 ratio for jack-rabbit starts or hilly conditions, but few of these were specified.

Designwise, the 626s were considered too short for so exalted a model. To many they seemed stubby, hard to distinguish from other roadsters. “They lacked the fleet lines that made cars look fast, the Cord, Auburn, Kisssel and [Stutz] Blackhawk, for instance,” wrote Morgan Yost. “Furthermore, the 1930 Packards had new bodies with the refined Dietrich influence and did not lend themselves to alterations. And, the short body space—only 79 7/8 inches—was just not enough to be comfortable, especially for a sedan.”13

A LeBaron heritage

Accordingly the 734 Speedster used the 733 Eight’s 134.5-inch wheelbase chassis, its frame rails modified to accommodate the larger engine. Finned, 16-inch brake drums, unique to this model, slowed the car as effectively as the big eight propelled it. But what really made the 734 impressive was its styling, the work of a talented triumvirate.

Raymond B. Birge, former general manager of LeBaron, had joined Packard in 1927 to set up its new custom body department. Birge himself was not a designer, so for the 734 project he brought in his former boss, Ray Dietrich, as a consultant. Most of the lines were established by Werner Gubitz, who had drawn for Dietrich before joining Packard. “It must have been like LeBaron Old Home Week when Dietrich arrived,” Turnquist wrote, “and it certainly indicated that the original LeBaron Speedster would be a strong influence….14

Gubitz’s high style

Werner Hans August Gubitz was born in Hamburg in 1899 and emigrated with his parents to New Jersey in 1905. His father, who worked at the American Lead Pencil Company, encouraged his aptitude for drawing with an endless supply of Venus colored pencils. By his early 20s Werner was a designer, making the rounds of car builders and coachbuilders, including Dietrich Inc. in Detroit.

“The Speedster was largely Werner’s,” Ray Dietrich told this writer. “He knew precisely how to execute a line on a surface. The famous ‘continuity of line’ which Packard maintained from the mid-1920s to the 1940s was also largely owed to him.”15

In 1927, cannily sizing up his prospects, Gubitz signed with Packard, where he remained for twenty years. “Whether it’s a coat-of-arms on a Deluxe heater or a cloissoiné emblem on the side of a hood,” wrote John Macarthur, you can bet Werner Gubitz had a lot to do with it.”16 W. Everett Miller, who worked alongside him in 1929-33, echoed that praise: “Werner was an unpretentious man with a soft-spoken Bronx accent, his German heritage being strongly evident. He was always rather shy, though eminently self-possessed…. There is no mention of him in The Inner Circle, Packard’s in-house publication, and he never received public recognition for his efforts during his lifetime. But his work, as Packard would say, was ‘of a distinguished family.’”17

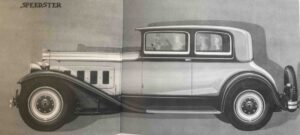

The production 734 Speedster

The result of this collaboration was a line of Speedsters three inches narrower and considerably lower than standard Packards, in five body styles. Most were phaetons and boat-tail runabouts (the latter with and without staggered seats). There were perhaps six each of the close-coupled victoria coupe and sedan. A fifth style, the four-seat rumble-seat roadster, was added in early 1930, according to Terry Shea: “…when a few customers inquired about such a version to accommodate more than just a driver and passenger, Packard responded with a very limited production model; just seven were sold. The roadster did away with the runabout’s sexy boat-tail, but suffers nothing in the looks department.”18 Overall production was thought to be 85 in 1981, but more 734s turned up, and today the production estimate is 117. All too few.

Packard charged $5200 for the open Speedsters, $6000 for the closed, with the customer’s choice of color and upholstery, since each car was individually crafted. Some bare chassis were also sold, and two customs were well publicized. The Packard Magazine featured them in 1930. One J. Brooks Nichols owned a Kirchoff-bodied runabout “that insures even less wind resistance [than the catalogued body]. Special treatment of [vee’d] radiator, front fenders and windshields front and rear, gives full sweep to the impression of swift grace which characterizes the car.” Also noted was Lt. J.R. Glasscock’s runabout by E.J, Thompson Coachworks, “which symbolizes in every line the graceful speed of its Packard foundation.”19 Fitted with Woodlites and cycle fenders, Glasscock’s car was spectacular—and may still exist. Back in 1981, a contemporary photo surfaced in Cars & Parts magazine. It would be nice to know if this exotic custom survives.

End of the beginning

Despite its belated attempt to build a customer base with the 734, Packard discontinued the Speedster in 1930, before the Seventh Series had wound up. The Depression was a factor, of course; but beyond that was the reluctance of higher management to use waning resources on what was admittedly a niche product. In those days, most people with $5000 to spend on an automobile sought smoothness, refinement, and above all, low-end torque. This made for a minimum of gear shifting and more comfortable rides on the rough roads of the time. Some enthusiasts express surprise that so wonderful a car could be discontinued. But to Packard at the time, there was nothing remarkable about it.

The Speedster idea was not altogether dead, however. In the hope that the Depression had bottomed, a new Speedster runabout was produced in August 1933. Mounted on the 135-inch wheelbase 1106 chassis, it was custom-bodied by LeBaron (by then run by Briggs). It sold for a then-staggering $7796, accompanied by a LeBaron sport phaeton. Edward Macaulay, son of Packard President Alvan, evolved a series of custom Speedsters beginning with his personal 745 runabout. None of these made it to production, and today fewer than a dozen 11th Series Speedsters are known.

Greatest of them all

The Speedster thus remained a fabled Packard, available only to a privileged few. It did not take long to be recognized as such. People were collecting them by the 1940s, long before there was an old car hobby, when most cars their age were regarded as obsolete derelicts. Those who knew what they had were rewarded by pride of possession, the joys of high performance and value for investment. Few blue chip stocks have produced better returns over the years.

They rank among the immortals. Driving behind Bob Valpey’s 734 roadster (in a 1936 One Twenty convertible that seemed to tower over it), I was struck by its spidery, ground-hugging stance, combined with the sheer presence of the car. Bob laughed off racing it, but it certainly looked like its name. With due deference to many fine models before and after, many will always think of the Speedster as the greatest Packard of them all.

Acknowledgements

Grateful thanks to the Packard enthusiasts and organizations who have added so much over the years to my knowledge of the Speedster: Stuart Blond of The Packard Cormorant, Conceptcarz.com, Raymond H. Dietrich, Jay Leno, John F. MacArthur, W. Everett Miller, Jerry Miscevich, the Packard Club, the Revs Institute, Terry Shea, Ronald Sieber, Dick Teague, Bob Turnquist, Bob Valpey and L. Morgan Yost.

Endnotes

- “Speedsters All,” in The Packard Magazine, Detroit, Spring 1930, 9.

- Robert E. Turnquist, “Utter Glory: Packard’s Immortal Speedster,” in The Packard Cormorant #23, Summer 1981, 9.

- Ronald Sieber, “Classic Speedsters,” accessed 30 July 2022.

- For details on these cars see “1916 Packard Twin Six Racer,” Conceptcarz.com, accessed 5 August 2021.

- L. Morgan Yost, Chapter XIV, Packard: A History of the Motorcar and the Company (Princeton, N.J.: Princeton Publishing, 1978), 303.

- “1925 Packard Model 236 Speedster Phaeton,” Conceptcarz.com, accessed 8 August 2022.

- “About the 1927 Packard Prototype Speedster,” Revs Institute, Naples, Fla., accessed 5 August 2022.

- Ibid.

- Charles A. Lindbergh to Robert H. Rand, 1 March 1958, in Turnquist, “Utter Glory,” 10.

- Jerry Miscevich to Jay Leno, 22 August 2016, accessed 5 August 2022.

- “Jay Leno’s Garage.”

- Richard M. Langworth, “The Packard Collection at the Henry Ford Museum,” in The Packard Cormorant #17, Winter 1979-80, 17-19. Yost, Packard, 304.

- Yost, Packard, 304-05.

- Turnquist, “Utter Glory,” 10.

- Raymond H. Dietrich to the author, Albuquerque, N.M., August 1974.

- John F. MacArthur, “Gubitz,” in The Packard Cormorant #90, Spring 1988, 17.

- W. Everett Miller, “The Brilliant Art of Werner Gubitz,” in Car Classics, April 1976. 38-41.

- Terry Shea, “Factory Force–1930 Packard Speedster Roadster,” in Hemmings Classic Car, July 2013.

- “Speedsters All,” 9.

More Packard

“Queen Mary: We Love Our 1950 Packard Eight Club Sedan,” 2022.

“Why Packard Failed, Part 1: Patrician and Its Relatives, 1951-53,” 2022.

“Why Packard Failed, Part 2: The End of the Road, 1954-1956,” 2022.

“The Packard: Ne Plus Ultra of Automotive House Organs,” Part 1 and Part 2, 2021.

Searcj also on this website for Dutch Darrin, Brooks Stevens and Don Peterson.