“The Packard”: Ne Plus Ultra of Automotive House Organs (2)

Continued from Part 1…. The Packard, the most elegant periodical ever published by an automaker, spanned the Packard motorcar’s golden age. Dwight Heinmuller of The Packard Club spent many years tracking and scanning the rare copies. Saving The Packard for posterity, he is posting high-definition scans on the club website. Since that post includes only excerpts of my 1981 history of The Packard, I publish the full text in two parts herein. RML

“Ask The Man Who Owes For One”

Packard’s longtime slogan was “Ask the man who owns one.” Frank G. Eastman, who succeeded Ralph Estep as editor, had the same piquant sense of humor. In a mock ad during 1917 Eastman drawled, “We build a good car and charge a good price for it—Ask The Man Who Owes For One.”

Chief truck engineer H.D. Church never signed his first name. Eastman pondered: “Hamm, Hamilcar, Harlo, Hermann, Hubert, Hernando, or is it just plain Henry? We don’t know. He signs his requisitions ‘H.D. Church’ and firmly refused to divulge for publication the label sprung upon him at the christening font.” (Factory hands called Church “Heavy Duty,” which, if true, was the ideal nickname.)

Making whoopee

Eastman also came up with the now-famous comment on an escaped murderer. In 1913 Harry K. Thaw, millionaire slayer of Stanford White, escaped from the Matteawan Asylum for the Criminally Insane in a Packard Six:

“When dependability is vital; when high speed is necessary; when a fast getaway is absolutely imperative, Ask The Man Who Owns One.” Safe across the border in Canada, Thaw duly wrote the company endorsing the product.

Eastman was chastened for making light of a somber event, but he came back swinging. Packards. he declared, were the favored transportation of the New York underworld:

“Innocent accomplices of ‘Lefty’ Louie, ‘Dago’ Frank and the rest. Jesse James, Dick Turpin and other outlaws of yesterday and the day before used the best horses obtainable. The selection of the Packard by the gun men of New York is, we insist, a matter of evolution and no reflection on the integrity of the car.”

Visual delights of the Packard marque

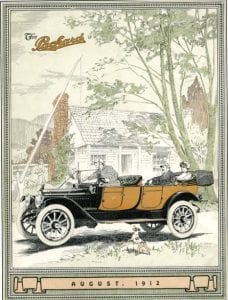

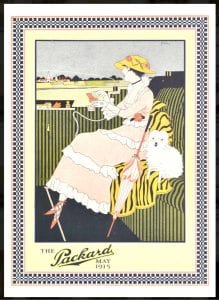

Integrity was exactly what Frank Eastman gave The Packard. He evolved its highly diverse cover style—no two successive issues alike. He frequently varied the paper stock and the typography.

Eastman recruited the best illustrators in the world: artists like Henry “Hy” Thiede, Earl Horter, R.S. Heinrich. The results were invariably a surprise, and always effective.

Eastman explained the rationale and means for those splendid covers in The Printing Art in 1915:

In our opinion the cover design is perhaps the most important factor in getting attention for the publication. There is so much diversity of method in handling different issues of The Packard that it seems almost impossible to arrive at average figures that mean anything….

The total costs for plates, including cover designs and illustrations, was $362. Printing, binding and mailing $1428. Paper, including cover stock $787. Envelopes $96; postage $835. The drawings cost $200; writing and editorial work and art supervision estimated at about $500.

My department has no means of measuring the concrete results of the investment in this form of publicity. We know that The Packard is an influence in keeping Packard owners in the family. We know it helps to promote the morals of the organization.

There are three points to keep in mind in conducting a house organ. First: To make it sufficiently interesting so that people will read it. Second: To have it reflect the character of the house. Third: To remember that the ultimate aim is to sell the goods.

Eclipse and rebirth

In the late Teens The Packard suddenly disappeared, replaced by an organ entitled Passenger Transportation. This was probably done to separate cars from trucks—the latter now had their own magazine: Freight Transportation Digest. But truck production ended in 1921 and Passenger Transportation was not on the same plane as The Packard. Frank Eastman was replaced as advertising manager by Frank H. McKinney in 1920, though whether McKinney edited Passenger Transportation is not known: the magazines carried no editorial credits from 1919 on.

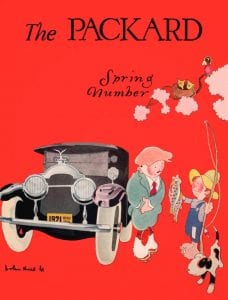

Evidently the austere, colorless appearance of Passenger Transportation caused McKinney to reconsider it. Thus a second generation of The Packard began, labeled Volume I, Number 1 in the winter 1920-21 “Show Number.” (Salesmen gave out thousands at the round of winter auto salons.) In 1927. the title was modified to The Packard Magazine, and thus it continued through its last issue in 1931.

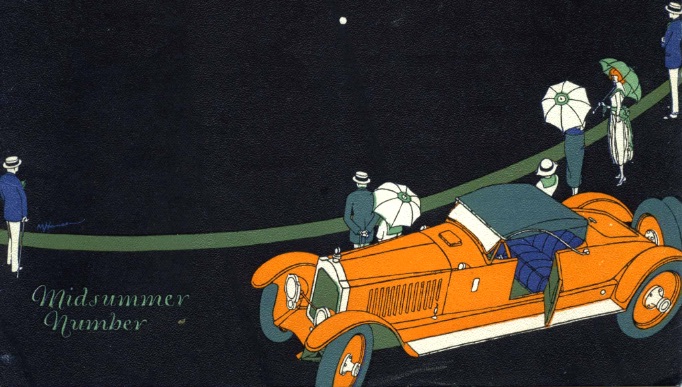

The Packard Magazine

If Estep had created The Packard’s concept, if Eastman had expanded the idea to include fine artwork, the new editors added a final touch: design excellence. The beautiful issues of 1927-31, printed on heavy coated paper, ran no more than twenty pages each. But each was a design masterpiece. Now. as the Art Deco age dawned. The Packard Magazine adopted thin. elegant typefaces, vignetted photography. John Held’s inimitable “Joe College and Flapper” cartoons decorated some issues.

Always there were striking four-color prints and paintings. In every way the magazine was the essence of the Packard motorcar in its golden age. In 1927, the summer cover was Gainsborough’s classic “Master Heathcote”—a painting sure to strike a chord with Packard’s clientele. Indeed the magazine was as worthy of a place on wicker settees or glass topped conservatory tables as The Literary Digest.

“Luxurious Transportation”

Autumn 1927 brought the first of Manning de Villeneuve Lee’s magnificent paintings depicting transportation contrasts, with a Western scene entitled “Blue and Gold.” From this point through its last issue, every number of TPM featured a striking Lee painting.

First came the “luxurious transportation” series (always including a Packard). Then a number of current events in which no Packard appeared—a bold departure for a car magazine. Commander Byrd’s voyage to the South Pole. President Hoover’s goodwill trip to South America, Gar Wood’s Packard-powered Miss America VIII, winner of the 1929 Harmsworth Trophy were all featured.

Each year there was a different border. The simple golden “picture frame” of 1928 was adopted for the cover of The Packard Cormorant on its first issue in Winter 1975.

The end of the road

The visual impact of The Packard Magazine forcibly overshadowed its excellent editorial content, punctuated by a return of some of the old humor. “Sedans may come, limousines may go, coupes roll on forever,” the editors said in the Twenties. But in “the zest of the Open Road, the Open Car beats all comers.” In 1928. when twenty-three 800-horsepower U.S. Navy planes were completing a quarter million miles of maneuvers at Guantanamo Bay, Cuba, the editors quipped: “The well-known Packard script is flying overhead to the tune of 200,000 total horsepower.”

Alas with the Great Depression, hard times came to America’s greatest luxury car. Time and money were now fast running out for Packard’s superlative magazine. It almost seemed as if Volume X, Number 1—the last issue, summer 1931—was the appropriate curtain call. It contained the final chapter of H.F. Olmsted’s history of Packard.

Olmsted himself provided the valediction: “With its new Twin Six recently announced, Packard bids fair to continue its stride to even greater heights. Already the enthusiastic reception which has greeted it world-wide indicates that the new Packard may fittingly take its place in the annals of Company achievement.” That was the famous Packard Twelve. And it did.

Ave Atque Vale

Through depression, recovery, recession, a second great war, temporary resurrection and demise, Packard publications fitfully came and went. But never did they duplicate that elegant sense of pace, editorial sensitivity, humorous style and high design found in The Packard Magazine.

In retrospect it was better that way. We wouldn’t have thought as much of it if, like so many other automotive house organs, it descended into the vulgar hucksterism of the Thirties and early Forties. It would have been heartbreaking to watch The Packard die alongside the company in the Fifties.

But among those for whom it had been an intrinsic part of the Packard family, the loss of the magazine was felt. For those who admire it today, the old yellowed pages are an infinitesimal microcosm of what was a great company at the height of success. They are much more valuable than the sterile if luxurious sales brochures. So thank-you Ralph, thank-you Frank, and thanks to your successors, for what you gave us.

That final issue ended with one of Packard’s arresting four-color illustrations of 1931: a majestic Deluxe Eight. Pictured front-on, it was a testimonial, as ever, to sheer integrity. Beneath it was a two-line statement that summarized the work of those who had created the finest automotive house organ in history, a slogan adopted on Packard Club publications today:

“This magazine reaches you as another evidence of our interest in your Packard ownership.’’