“The Packard”: Ne Plus Ultra of Automotive House Organs (1)

The Packard, the most elegant periodical ever published by an automaker, spanned the Packard motorcar’s golden age. Dwight Heinmuller of The Packard Club spent many years tracking and scanning the rare copies. Saving The Packard for posterity, he is posting high-definition scans on the club website. Since his accompanying article includes only excerpts of my 1981 history of The Packard, I publish the full text in two parts herein. RML

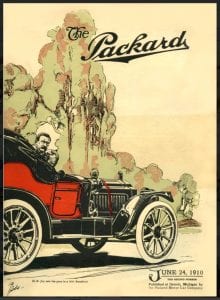

1. The Packard: setting the standard, 1910-11

“I am much pleased with the idea of publishing a periodical intended to circulate among all who are interested in Packard welfare,” wrote General Manager Alvan Macauley in June 1910.

“Its most important office will be as a medium for the exchange of ideas and information…. Its columns should be open to all, and contributions should be welcome. It might contain preachments intended to make clear to all who read what a wonderful piece of mechanism a Packard car is.”

Alvan Macauley could have been thinking about the Packard Club magazine today, capably edited by Stuart Blond. In 1975 it was The Packard which inspired the design of the new Packard Cormorant. To this day that magazine duplicates The Packard’s cover styIe, margins, logos and typefaces. Occasionally we approximate The Packard’s engaging style, common only to a few business journals.

The Packard was not the company’s first periodical. That was Small Talk, first issued in December, 1902. Edited by Sidney Waldon, then advertising manager, Small Talk was a modest newsletter containing letters from happy owners.

Waldon replaced it with the more elaborate Packard Pointers. This lasted through the company’s remaining years in Warren, Ohio, but ceased publication after the move to Detroit in 1903.

In Michigan Packard consolidated its new Grand Boulevard factory, updated and improved its cars, and ultimately evolved the standard-setting Model Thirty.

In 1907 Waldon became sales manager, and his place was taken by Edwin Ralph Estep. Three years later Estep produced The Packard Number One.

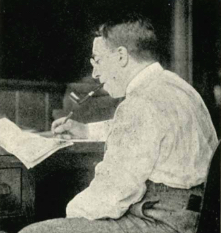

Ralph Estep: present at the creation

Estep was a short, bespectacled, roundish gent with a prodigious liberal arts education, a warm style, and a sure sense for quality and elegance. “Before Estep took over,” wrote historian James J. Bradley, “Packard ads verged on the amateurish—loudly assertive of feats, runs, reliability trials and speed records. Estep imparted to Packard advertising the same aura of class and sophistication of its sales agencies and the cars themselves.”

A testimonial called Ralph “the pioneer developer of scientific automotive publicity.” More than a publicist, he was a poet, humorist and man of letters. He produced the first truly memorable automotive literature.

Estep’s first effort at Packard was a spectacular catalogue for the 1908 Model Thirty. A deluxe version for special friends of the company featured a double-page “credo” in hand-lettered Old English, trimmed with gold leaf.

The frontispiece color engraving was tipped-in by hand; the cover was heavy, grooved white vellum with gold embossments of the Packard radiator. Each copy cost $35 ($900 today).

The advertising budget was only $40,000 a year, but in 1910 Estep convinced management that a periodical was needed. Thus emerged The Packard. Ralph left in 1912, but remained close to the company and its magazine for the six years remaining to him.

In 1917 he joined the American Expeditionary Force. He was killed in action at Sedan on 7 November 1918, four days short of the Armistice. Six other former employees had given their lives in the “war to end wars.” All were honored in The Packard under the title, “Their Name Liveth Forevermore.”

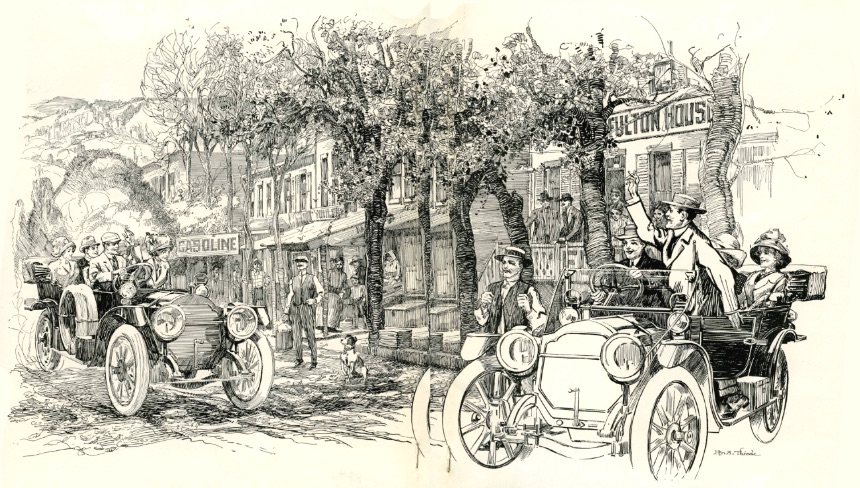

Puckish humor, visual delights

Though Estep produced only twenty-nine issues of The Packard, they set the tone for the eighty-one which followed. We cannot overestimate their beauty, Bradley wrote, nor “the priceless record they contain of the young company’s aspirations and philosophy….

“Detailed reports covered technical developments and construction of everything from bodies to steering wheels. The Packard recorded daring cross country trips, dealer news, essays on the efficacy of square dealing, advice to owners.”

Estep’s whimsical sense of humor was early evident in his pages. The Packard was laden with cartoon spoofs of prominent dealers. It was capable of atrocious puns.

A dealer moved from Texas to Alabama. Estep said he was “now down Old Mobile selling Packards.”

When Packard announced plans to class body parts as animal, vegetable or mineral, Ralph said buckram and duck would go into the animal section: “If buck, ram and duck are not animal, what the deuce are they?”

Ralph was close to sales manager Sidney Waldon, whose long-distance endurance runs were legendary. He was constantly poking fun at his friend.

In 1911 he ran a mock ad promoting Waldon’s farm, under the heading, “Pigs is Pigs. We hate to break up a happy family, but are now prepared to book orders for pigs from spring farrowings.” Eggs, too, were for sale, but “if they don’t hatch, don’t blame us; try another incubator.’’

“Seth Saith”

Another amusing feature of The Packard was its columns, such as “Seth Saith,” full of homely philosophy: “Harmony doesn’t mean serenity. Serenity ignores the troubles of others. It is often selfish.”

Another amusing feature of The Packard was its columns, such as “Seth Saith,” full of homely philosophy: “Harmony doesn’t mean serenity. Serenity ignores the troubles of others. It is often selfish.”

Sprinkled in were quotations from poets like Tennyson and Browning. Tennyson’s poem “Rabbi Ben Ezra” was prominent.

Always The Packard poked good-natured fun at corporate executives. In a 1910 issue Estep likened the top brass, including the straitlaced Macauley, to a brood of chickens “just hatched out at the factory”:

We understand that S.D. Waldon will have large steel gray wings, while Mr. Macauley’s pin feathers give indications of his flappers being somewhat similar in color to those of a meadow lark. Ramsey is not feathering out at all well but gives evidence of being a rare old bird.

Each of the fledglings had to dig up one dollar. The mother hen was Russell A. Alger [Secretary of the Corporation and former Member of Congress] who thought the U.S. needed the money and who, we understand, is very proud of the brood.

“Replies to the Curious”

A question-answer column posed dummy questions, for which Estep constructed his own bizarre answers:

“The Packard aims to answer all questions promptly. Working our Query Editor overtime and keeping an ice pack on his head, we obtained answers to the following questions….”

Q: What is the name of the part that can whiz and whirr so that the sensation is as if one were amongst mill machinery and that causes the whole car to vibrate, hum and make the occupants miserable?

A: The name of this part is the motor. The whizzing and whirring are readily stopped by taking a wire cutter and cutting all the wires you can see.

Q: What are the names of the parts of the machinery under the car floor?

A. It depends largely on the car, the extent of the floor and whether you look the names up in the parts price list or ask Technical Manager Stowell, who is a noted namer. Anyway, among Packard owners very little is known about what is underneath the car floor.

The Q&A column ended with a confessional: “After this severe mental strain the Query Editor is working on the higher mathematics and differential calculus as a mild form of relaxation.”

Packard, always Packard

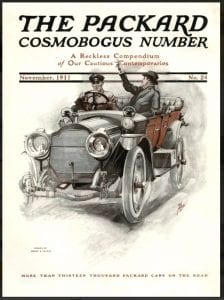

Estep went out in a blaze of fun. The Packard for November 1911 issue, one of his last, was the “Cosmobogus Number.” Brimming with dummy pages from distinguished periodicals, it contained, of course, only Packard articles.

Cosmopolitan, The New York Times, Colliers, McCall’s and The Saturday Evening Post were all imitated. Estep called this satire “A Reckless Compendium of our Cautious Contemporaries.” Each page paid some kind of tribute to the product, which was fast becoming the preeminent American luxury car.

And that was the whole idea, wasn’t it? The Packard was a celebration—of all that was best in a young, dynamic company. The grand marque couldn’t have had a better champion.