Virgil Exner, Part 1, Studebaker: How Ex Marked His Spot

The story of Virgil Exner was originally published as “Father of the Tailfin” in The Automobile (UK) for August 2024. This first of a two-part article records how “Ex” began his career with Studebaker, a piece of good timing that stood him well.

A name we all knew

Motorcar designers rarely become household names. Harley Earl, who invented the styling profession at General Motors in the 1920s, was better known after he retired. His successor, Bill Mitchell, more widely recognized, loved the limelight. He was always ready to be photographed riding his Harley-Davidson motorcycle in his chrome leather jacket.

Pininfarina’s name got round in America because it appeared on everything from Nashes to Ferraris, but relatively few knew of Nuccio Bertone, or even, later, Giorgio Giugiaro. The name Raymond Loewy was known to some through his gifted self-promotion. But Howard Darrin—similarly talented—was more famous as a 1930s custom body builder than a 1950s car designer.

Yet every kid in late-Fifties America knew of Virgil Exner. Through them, their parents knew of him, and bought his cars. To become as famous as Ex was by, say, 1958, a designer has to create something singular—something that heralds a new epoch. Almost alone among his contemporaries, Ex did just that. He was the “father of the tailfin.” And the tailfin (copyright Chrysler Corporation, 1956) was as recognized a symbol of late Fifties America as Elvis Presley.

Young Virgil

Like many automotive designers, Exner grew up with cars in his blood, transfused from the places he frequented. He was born and immediately adopted by German-American parents in Ann Arbor, Michigan in 1909. Barely 17, he enrolled at Notre Dame in South Bend, Indiana, near the busy factories of Studebaker. He dropped out of university for lack of money after 2 1/2 years and applied for work at a local firm, Advertising Artists, which produced Studebaker catalogues.

Michael Lamm and David Holls, in their seminal book, A Century of Automotive Style, tell us that Exner began by painting picture backgrounds: “But when his boss noticed how good he was, he gave Ex the task of illustrating Studebaker cars and trucks…. He also developed a knack for sculpting in clay, all of which later helped him as a car designer.”

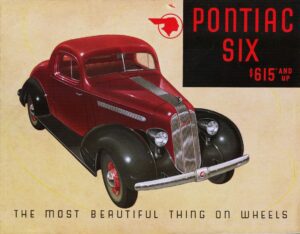

In 1934, hearing about Harley Earl’s Art & Colour Studio at GM, Ex hied to Detroit and his first design position, at Frank Hershey’s Pontiac department. An early assignment was contributing to the visual unity of 1935 Pontiacs with the iconic “Silver Streak.” This was a broad band of grooved bright metal that ran from the grille down the hood and repeated on the deck. The Silver Streak was a Pontiac hallmark through 1956. When Frank Hershey was transferred to Opel in 1937, Exner became Pontiac’s chief stylist. But by that time he was already being courted by the famous Franco-American industrial designer, Raymond Loewy.

Ex meets Ray

Loewy, who had secured the Studebaker account in 1936, was in serious need for design talent. His eye soon lit on Virgil Exner. Harley Earl liked and admired Ex and wanted him to stay at GM. But Loewy offered a big salary increase and a New York location. Virgil moved his family to Long Island, only to find himself back in familiar South Bend in 1941, after Studebaker insisted that Loewy locate his design team at its factory.

In Indiana, Exner and clay modeler Frank Ahlroth were soon joined by Robert Bourke, who would later create Studebaker’s famous 1953 “Loewy coupe.” Following Pearl Harbor, Studebaker designers and engineers were harnessed to the war effort. Exner, Bourke and Ahlroth found themselves designing air-cooled turbocharged aircraft engines. In their spare time, the trio worked on ideas for the eventual postwar Studebakers. Meanwhile, as Bourke remembered, “Raymond Loewy was busy convincing management to accept these radical designs for the postwar era.”

“Weight is the Enemy”

Given the size of the design department and the minimal time for cars, Exner’s group had revolutionary ideas. Integral fenders were unheard of in those days. So were vast areas of curved glass, or doors cut into the roof. Loewy detested the use of chrome as embellishment. He preferred slim, tapered shapes, and practical devices like glass or clear plastic headlamp covers to improve streamlining.

Loewy also preached lightness, warning of the cost of excess weight in fuel consumption and performance. Throughout the studio, on walls, floors and ceilings, he posted signs reading: WEIGHT IS THE ENEMY.

Loewy told this writer: “I tried to convince management that there existed among Americans a segment, profitable to Studebaker, that could not find the kind of car they wanted among GM, Ford and Chrysler offerings. What these consumers wanted was a sleeker, compact automobile with European-type roadability and good acceleration.” A leading newspaper, he added, “credited me with being first to use the word ‘compact.’”

Raymond Loewy in those years was no longer a hands-on designer. Having brought his company to prominence, he preferred now to hire good talent, supervise their work, approve what they produced, and sell it to clients. Thus Loewy was rarely at South Bend. Virgil Exner became his point-man with Studebaker management. Inevitably, an antipathy developed between Loewy and Exner—and, more seriously, between Loewy and Studebaker chief engineer Roy Cole, a stolid Midwesterner who had never cared for the flamboyant Frenchman.

A certain discontent

Ex, who was doing a lot of the work, easily bought Cole’s argument that Loewy was more figurehead than contributor. “The problem was basically a disagreement in philosophy,” the evenhanded Bob Bourke remembered:

Ex felt that a man was either a designer or a promoter, but not both. To make matters worse, he felt Loewy received all the credit from management and the public.

Although I understood Ex’s viewpoint, I still held R.L. in high regard. I recognized the necessity of being a good salesman in this profession. Mr. Loewy also had a great “eye.” While he may not have created a certain line or contour, he knew instinctively when a designer had better than average talent and drive, and he would always bring out the best that designer had to offer the client.

While Ex and Cole nursed discontent, the Loewy team began evolving postwar Studebakers. They began slowly, but with more urgency as the war neared its end. More personnel came on board. Exner found himself heading a distinguished circle: Bourke, Gordon Buehrig, Holden Koto, Ted Brennan, John Cuccio, John Reinhart, Vince Gardner and Jack Aldrich.

Reinhart would later design the image-shattering 1951 Packards and direct styling for the 1956 Continental Mark II. Gardner would contribute to the Mark II and other Ford designs. Buehrig was noted for his rakish prewar Auburns and Cords. Koto would aid Bourke on Studebakers through the ‘53, and he and Bourke freelanced the front clip of the ‘49 Ford. Loewy considered this team the best in the industry.

Studebaker’s radical postwar plans

The 1947 Studebakers were the first all-new designs from a prewar car company. They were conceived by the Loewy Studios under Virgil Exner. As early as 1942, they had settled on a full-width body rather than freestanding fenders. Later they integrated the fenders with the body sides, but left enough of a bulge to avoid a slab-sided appearance. They developed a curved one-piece windshield; a wrap-around backlight (for what became the 1947-52 Starlight coupe) and a long, tapered rear deck. Although many rival companies developed similar ideas, Studebaker put them into production at years before anyone else.

The break between Raymond Loewy and his ambitious young designer came in the spring of 1944. As Exner recalled, one morning Roy Cole walked into his office, accompanied by Studebaker President Harold Vance. Cole had a proposal. Would Ex undertake secretly to design a production car, independent of the Loewy Studios?

He didn’t trust Loewy to come up with anything practical, Cole explained, but couldn’t prove he was right without competition. Vance nodded agreement, but cautioned that Ex would have to work on his own time at home. Neither he nor Cole were willing at that point to risk confrontation with Loewy, who was still under contract.

Exner told this writer that he didn’t take much persuading:

I agreed to start immediately. I cleared out one of my bedrooms at home and they sent me an eight-foot drafting board. Then we went into my basement, and they built me a quarter-scale clay modeling table. Eugene Hardig, who was then chief of chassis drafting, came out every day…. We worked on seating and chassis layouts…. This lasted about three to four months. On completion the rival design was still a pretty good secret, even at Studebaker.

Ex knew that his actions would seal his fate with Loewy, but he was young and ambitious, determined to show what he could do. Many can imagine how he felt, working against tight deadlines at home, visions of a revolutionary new car dancing in his head.

Dimensional shuffle

A curious error now came to Exner’s assistance. The initial dimensions Cole gave him for the new Studebaker Champion, like those handed to the Loewy team, were impractical. They called for a wheelbase of only 110 inches and a width of just 67 inches–much too small for a “family car.”

Ex remembered: “Roy Cole had a thing: His philosophy was that a car cost so much a pound. He stuck to that rigidly, and these were the dimensions he laid down. They were a little tough to work with.” That was an understatement. Cole’s proposed chassis was too narrow, the car too short, the entire geometry unworkable.

Exner pleaded for more generous dimensions. Surely they could allow 70 inches of width and open the Champion wheelbase to 113? (It expanded to 120 inches on the senior Commander, 124 on the stretched-out Land Cruiser.) Anxious to please his favorite stylist, Cole relented. Exner continues:

We then built an all-new wooden mock-up. The body drawings were simply opened up and a three-inch strip put down the center without changing the profile, and the wheels were moved back. Then the front end looked too short [so] I convinced Mr. Cole that we should add three inches to the fenders and two inches to the hood.

An inch here, an inch there, and pretty soon you’re talking about real changes. There was one other factor: Roy Cole didn’t bother to advise the competition. The “official” Loewy Studios team, still ostensibly under Exner, laboured on with a foreordained loser—“sort of an underhanded deal on the part of Cole,” Bob Bourke recalled…

because he was trying to get Loewy out of there. We did two full-sized plaster automobiles, and when management viewed them, they said they were just too narrow. In a matter of a week, we cut them right down the middle and expanded them out to where the Exner jobs were, but by then the Exner model was being tooled for production.

The break with Loewy

When Studebaker selected Exner’s rival model, Loewy exploded, jumped aboard the Twentieth Century Limited (which made him no happier because the train was designed by his arch rival Henry Dreyfus), and headed in high dudgeon for South Bend. There he fired Exner for disloyalty and insubordination. This had been foreseen: Ex was immediately rehired by Roy Cole as chief body engineer.

From a study of his design ideas and subsequent career, as well as the prototypes, it is virtually certain that the high hood and complicated stainless steel grille were Exner contributions to the original Loewy shapes. These were in some contrast to Loewy’s preferred sloping hood and minimal chrome. But Exner’s idea was probably more in keeping with contemporary tastes. “Ex favoured this type of hood more than I did,” Bourke said. “I was equally to blame, however, as I had done many studies for Ex along these lines.”

With Exner out, Bob Bourke became the head of the Loewy Studios at Studebaker. Through Roy Cole, Exner enjoyed job security, competing (unsuccessfully) with the Loewy team for the 1950-51 facelift with its famous “bullet-nose.” But Ex’s disloyalty to Loewy, and moreover to the likeable Bourke, did not endear him to many.

Nearing retirement, Cole realized he couldn’t protect Exner forever, and canvassed industry friends in need of a stylist. He found a berth at Ford, and the Exner family was about to move to Dearborn when Ford signed a design contract with George Walker. Cole then called his friend K.T. Keller, President of Chrysler. The rest, as they say, is history.

Related reading

“Why Studebaker Failed,” 2020.

“Why Packard Failed,” 2022.

“‘All the Luck’—Howard A. ‘Dutch’ Darrin,” 2017.

“Indie Auto: Did Detroit Give Us the Dinosaurs?” 2023.

“Kaiser-Frazer and the Making of Automotive History,” 2019.