Virgil Exner, Part 2, Chrysler: Birth of the Tailfin

The Exner story was originally published as “Father of the Tailfin” in The Automobile (UK) for August 2024. This second of a two-part article records how Ex triumphed at Chrysler, where he created the tailfin, symbolic of America in the Fifties. Concluded from Part 1….

Virgil Exner

(From Part 1….) Motorcar designers rarely become household names. Yet every kid in late-Fifties America knew of Virgil Exner. Through them, their parents knew of him, and bought his cars. To become as famous as Ex was by, say, 1958, a designer has to create something singular—something that heralds a new epoch. Almost alone among his contemporaries, Ex did just that. He was the “father of the tailfin.” And the tailfin (copyright Chrysler Corporation, 1956) was as recognized a symbol of late Fifties America as Elvis Presley.

Ex at Chrysler

Virgil, his son recalled, “wasn’t exactly the most welcome person who ever showed up at Chrysler Corporation:

Predecessor stylists viewed him as a usurper. Dad set up a small studio and began working on his own, without a definite production goal but relatively free to come up with some good workouts. With these he hoped to point Chrysler in what he felt was the right direction.

Certainly past directions had been doubtful:

Dad called the Chrysler Town & Country a “lumber wagon.” He looked upon it as a car that “hadn’t been uncrated.” He liked woodies, but was very much a believer in the all-steel station wagon [pioneered by Plymouth in 1949]. Of course he thought the boxy 1949 Chrysler body styles were just awful. [Chief body engineer] Henry King was a good designer, but really his talents were kind of wasted through that era.

Changing the image

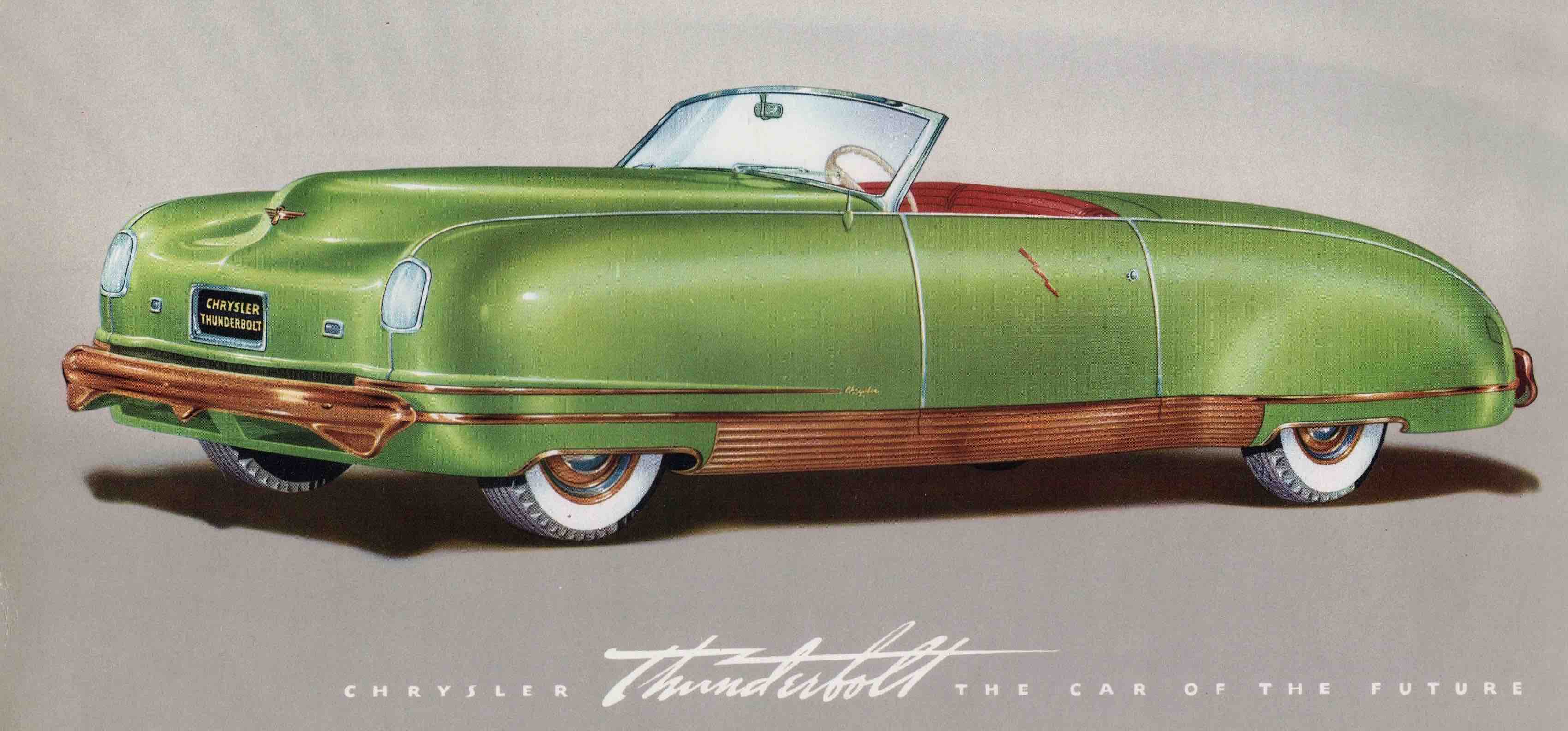

Exner’s first projects were a remarkable line of show cars, designed to prefigure production car styling. President Keller and Tex Colbert, who replaced Keller when K.T. became Chairman in late 1950, had always liked Chrysler’s clean-lined prewar idea cars, the Thunderbolt and Newport. They wanted more of them. “Old K.T.” is often blamed for Chrysler’s boxy look in the early 1950s. In fact, he was acutely aware of, and meant to change, this styling disadvantage.

In 1949, Keller had asked Pininfarina to explore future styling directions with a trim four-door sedan on a New Yorker wheelbase. Later, in 1951, Ghia in Turin produced the Plymouth XX500 special. Virgil, Jr. told this writer that the XX500 “was brought over by Ghia to show Chrysler their ability and craftsmanship. It was pretty dumpy, but it started the whole idea in Dad’s mind that they could build real experimental cars, as opposed to mock-ups.”

Chrysler engineer Fred Zeder, a fan of Exner’s, remarked: “We like to see just how these ideas work out in an actual, operating automobile.” Rival companies “build dream cars which quite obviously couldn’t be produced on an assembly line.” Exner chose Ghia over Pininfarina because Ghia could produce one-offs at modest cost. His first Ghia special, the K310, cost only $10,000, an astonishingly low figure, even then.

The Ghia-Chryslers

A classic car enthusiast and a student of world industrial design, Exner brought a sophisticated approach to Chrysler styling. He admired what he called the “Italian Simplistic School.” Italian designs “were thoroughly modern, with subtly rounded shapes and sharp accents indicative of genuine character.”

While Exner’s show cars were influenced and built by Ghia, most of them began life on his own drawing board. The K310 (K for Keller, 310 for its supposed horsepower) seriously influenced production design, notably the 1955 Imperial–as did its convertible counterpart, the C200.

Successor models were the Ghia Special, GS1 and d’Elegance. Here Exner introduced bold, squared-off grilles and combination bumper-grilles that were later seen in production cars. (Incidentally, the GS1 was evolved by Ghia into the VW Karmann Ghia—independent of Exner, of course, downsized, and minus GS1’s huge egg-crate grille).

Shown at Chrysler dealerships nationwide, the K310 and its successors sparked new interest in Chrysler design. Exner then began to contribute to production car styling. His influence on the restyled 1953-54s was slight, though he did spark more shapely, rounded forms than those of 1949-52.

The show cars that directly led to Exner’s glory years were the Parade Phaetons. Three 1952 Crown Imperials with production front clips were mounted on extended, 147 1/2-inch wheelbase chassis. Later they were updated with 1955-56 styling. Based on clay models from Exner’s studio, they featured a strong character moulding along the beltline, a rear fender “kick-up,” and big, open wheel wells. Even Exner didn’t anticipate the influence these cars would have–owing in part to events beyond his control.

Salvaging Chrysler

Chrysler Corporate sales in 1953-54 were grim. Four years of dull styling, coupled with a production blitz and heavy dealer discounting by GM and Ford, left Chrysler in a slump. By 1952, Ford had regained second place in American car production for the first time since the 1930s. In early 1953, Keller asked Exner’s opinion about the 1955 models then aborning. Exner had a look and replied in one word: “Lousy.”

“K.T. Keller kind of liked that,” Virgil, Jr. remembered, “since he was quite a strong character. So he said to my Dad: ‘Okay, you put it together—you have eighteen months.’ Dad swiped stuff off the parade phaetons and did manage to put the ‘55 line together in time. He did it with a tiny group of only seventeen people, including the modelers and four or five designers.”

(Virgil, Jr. refers here to the Imperial, Chrysler and DeSoto. The 1955 Dodge and Plymouth, although new, were not based on the Parade Phaetons, but designed separately by Henry King and Exner associate Maury Baldwin. Exner signed off on them too, of course. He had now become chief of Chrysler design.)

The “Forward Look”

The outcome of all this was the dramatically restyled 1955 model line. Almost overnight, they altered Chrysler history.

The most obvious descendant of the Parade Phaetons was the 1955 Imperial, one of the classic designs of the Fifties: uncluttered and understated, except for the gaudy ornaments on hood and deck, and the “gunsight” taillights, a throwback to the K310.

Chryslers had their own look, with huge “Twin Tower” taillights and smaller grilles surmounting a horizontal bar up front. DeSoto kept its established toothy grille, topped by an ornate bonnet badge. Its most radical feature was a “gullwing” dashboard, housing instruments and controls under the steering wheel and a glovebox/radio speaker at right.

Taking the lead

The 1955 Dodge and Plymouth also saw remarkable improvement, with longer, cleaner lines and curved body sides. Vastly altered, they didn’t seem related to their predecessors. Both enjoyed enormous buyer approval. All five makes were successful: Chrysler Corporation recorded the highest dollar volume and unit sales in its history, with a seventeen percent slice of ‘55 output compared to only thirteen in 1954.

In retrospect, there’s no doubt that the 1955 “Forward Look” Chrysler products were among the best American designs of their decade. Without the garish two- and three-tone paint jobs so many fashionably wore, they still look clean and well balanced today.

These were the cars which began to wrest the design leadership that had belonged to General Motors since the late 1920s. By 1957, Chrysler held one-fifth of the market and GM was hastening to keep pace. So was everybody else. It must have galled Raymond Loewy to see his famous coupes, now called Studebaker Hawks, sprout tailfins in a hasty attempt to ape Exner.

Birth of the tailfin

Virgil Exner had become a vice president, with a design staff of over 300 and a name known nationwide. His interest in the tailfin, the feature for which he was best known, became evident on the 1956 models. His son thought he was inspired by the Ghia Gilda, a dramatic fastback which was mainly one long fin. Also influential were the Alfa Romeo BAT and Chrysler’s own Dart show car.

“He was a staunch believer in fins,” Virgil Jr. continued:

The idea was to get some poise at the rear of the car–to get off of soft, rounded back ends, to get some lightness to the car. Fins were a way to do it aesthetically, and were genuinely functional. They ran tests at Chrysler and without trying to rationalize, they did work. They moved the centre of air pressure back, a little closer to the centre of gravity, provided more inherent directional stability. True, the effects weren’t much evident below 80 mph! It wasn’t a pure style, but it was functional. Dad always tried to make his tailfins as simple as possible, as opposed, say, to the 1959 “batwing” Chevrolet.”

Flite-Sweep styling

The best of Exner’s finned creations were the first “Flite-Sweep” models of 1957-58, particularly the simple, dramatic Chryslers. The most important thing about them was their revolutionary lowness, which was no accident. Exner had demanded that they stand five inches lower than the ‘56s. This was a huge reduction.

Chrysler engineers said it couldn’t be done. They did it anyway, with the help of such space saving innovations as 14-inch wheels, thin-section air cleaners, pre-formed headliners and (importantly) torsion bar front suspension.

With acres of glass, low beltlines and slim roof pillars, Flite-Sweeps were unchallenged by any rival and prefigured the shape of American cars for the next half decade. Coupled with such innovations as “Torsion-Aire” ride, TorqueFlite automatic and potent V-8 engines, they represented a pinnacle, a company reborn. They were Virgil Exner’s finest hour.

But time is always running. In mid-1956, as the Flite-Sweeps were about to be introduced, forty-seven-year-old Virgil Exner suffered a massive heart attack. Colbert brought in Bill Schmidt, late of Studebaker-Packard, as his temporary replacement. Ex recovered and returned to work a year later. But his post-1958 designs lacked the chiselled smoothness and drama of their predecessors, and sometimes just looked odd.

Tailfins grew higher, clumsier and less functional; Ex’s penchant for classic era features led to “toilet seat” spare tires on rear decks and “freestanding” headlamps, which on cars like the Imperial only looked bizarre. He did win a design award for his 1960 Plymouth Valiant and its clone, the ‘61 Dodge Lancer—Chrysler’s first compacts. But after all, he had always preferred light cars.

“Plucked chickens”

The last line of full-size Chrysler products designed completely under Exner came in 1962. It was a very mixed bag. The Chryslers were basically ‘61 models shorn of fins—Ex called them “plucked chickens.” Dodges and Plymouths emphasized his long bonnet/short deck concepts, but they were prematurely downsized, stubby in appearance. Sales dropped, overcome by full-size competition from GM and Ford.

Meanwhile Chrysler Corporation was suffering political upheavals and financial scandals. Shortly after the ascension of President Lynn Townsend in mid-1961, Elwood Engel replaced Exner as vice president of styling. By the early Sixties, GM styling was again pacing the industry.

Exner, who closely influenced the, chunky, chiselled 1963-64 models, remained a styling consultant through 1964. But it was clear that his Chrysler career was winding down.

Trail’s end

In 1961 Virgil joined his son in a private design firm, Virgil M. Exner Inc., in Birmingham, Michigan. Here he produced artwork for an Esquire project: three classic revivals, the Duesenberg II, Stutz Blackhawk and Mercer Cobra. Exner Inc. also engaged in automotive projects for U.S. Steel and Dow Chemical. Ghia’s Selene II, the Renault Caravelle and Bugatti Type 101 bore traces of his hand.

Virgil Max Exner died in 1973, leaving a legacy of imagination and innovation. Not only was he one of the few car stylists known broadly in America. He was the first to topple General Motors as Detroit’s styling leader. In a very real sense, too, Ex had saved Chrysler in the mid-Fifties. His cars were among the last that could trace their shape to a single gifted individual.

Bibliography

Richard M. Langworth: Chrysler and Imperial: The Postwar Years, 1976; Studebaker: The Postwar Years, 1979; Encyclopedia of American Cars 1930-1980, 1984. With Jan P. Norbye The Complete History of Chrysler Corporation: 1924-1985, 1985. Michael Lamm and David Holls: A Century of Automotive Style: 100 Years of American Car Design, 1996. Author’s interviews: Maury Baldwin, Robert E. Bourke, Gordon M. Buehrig, Virgil M. Exner, Virgil Exner Jr., Eugene Hardig, Raymond Loewy, John Reinhart.

The great designers

“Virgil Exner, Part 1, Studebaker: How Ex Marked His Spot,” 2024.

“Brooks Stevens: The Seer Who Made Milwaukee Famous,” 2022.

“The Greatness of Alex Tremulis,” Part 1 of a three-part article, 2020.

“‘All the Luck’—Howard A. ‘Dutch’ Darrin,” 2017.

“Indie Auto: Did Detroit Give Us the Dinosaurs?” 2023.

“Kaiser-Frazer and the Making of Automotive History,” 2019.