Anti-Bolshevik Collaborators? Reilly, Ford, Savinkov, Churchill

Excerpted from an article for the Hillsdale College Churchill Project. For the unabridged text with endnotes, please click here. To subscribe to posts from the Churchill Project, click here, scroll to bottom, and fill in your email in the box entitled “Stay in touch with us.” Your email address is never given out and will remain a riddle wrapped in a mystery inside an enigma.

Q: Churchill, Ford and Reilly

“I believe Churchill crossed paths with Sidney Reilly, the famous ‘Ace of Spies,’ vividly portrayed by Sam Neill. I’ve read that Henry Ford, like Reilly and WSC, was a strong anti-Bolshevik. Did they ever meet to coordinate their activities?”

A: Not a threesome

It’s a logical question, but there is no evidence of counsel between Reilly, Ford and Churchill. All three were stridently anti-Bolshevik, but there their characters diverge. For one thing, Ford was a virulent anti-Semite. This would not have appealed to Churchill, let alone Reilly (the former Sigmund Rosenblum).

Churchill did praise Ford in 1918, when WSC ran the Ministry of Munitions. Churchill placed an order for 10,000 “cross-country caterpillar vehicles from several American manufacturers. Ford’s “vast organization,” he wrote, executed “this contract without detriment to their other obligations.” Whether they met personally at the time is doubtful.

A decade later, planning his North American holiday, Churchill had “promised Mr. Ford to see his Works at Detroit.” But I found no correspondence between them. Later, Ford became a passionate isolationist, which would render him no ally of Churchill’s.

Sidney Reilly was a different story. Churchill’s connections with him ran from the Great War to the early 1920s. But Churchill later downplayed their relationship. In 1931, Reilly’s wife was preparing to publish his autobiography, and Churchill expressed concern to his intelligence advisor Desmond Morton: “I have for some time heard talk of Reilly’s memoirs and papers being published. It is quite possible they contain some indiscreet stuff.” The publisher reassured him: “Captain Reilly included several lofty appreciations of yourself, but I have deleted them on the supposition that you would not care to have your name too frequently mentioned in a book of this nature.”

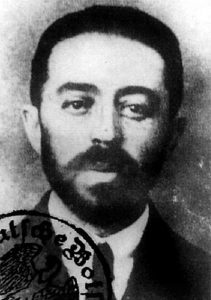

Reilly, née Rosenblum…

…was born the same year as Churchill, in either Grodno (Hrodna, now Belarus) or Odessa, Ukraine (sources differ). Like his ally Boris Savinkov, he rebelled against both the Czar and the Bolsheviks. Both fitted Churchill’s colorful description of Savinkov: “a terrorist for moderate aims.…freedom, toleration and good will—to be achieved wherever necessary by dynamite at the risk of death.”

Reilly landed in Britain in 1895 and was soon involved in clandestine affairs. Before the Russo-Japanese War, he spied for the British and Japanese in Port Arthur. There he stole Russian plans for the harbor defenses, conveying them to the Japanese for a naval attack. Reilly’s actual accomplishments are murky and controversial. One of these was in Germany, where he posed as a welder in the Krupp Gun Works, supposedly stealing German armament plans. Some historians have him playing a double role, such as selling munitions to both the Germans and the Russians.

Reilly had a long relationship with Mansfield Smith-Cumming (“C,” the first head of Britain’s Secret Intelligence Service (MI6). After the Bolshevik Revolution Reilly slipped into Russia, attempting to aid anti-Bolsheviks and topple Lenin. Here he met and plotted with Savinkov. Wikipedia has a lengthy entry on Reilly’s career.

Churchill and Reilly

Churchill’s romantic nature “drew him to mavericks and buccaneers, unorthodox figures who defied convention,” wrote David Stafford. “The extravagant plots of Reilly and Savinkov interested Churchill, who gave them all the support he could, and although their plots failed he remained mesmerised by the potential of covert action behind enemy lines to cause mischief and mayhem.”

In August 1921, Stafford noted, Reilly wrote “a lengthy assessment of the Russian situation that he passed to Churchill. The two met and Churchill spoke of taking him to meet Lloyd George.” The report predicted “a general uprising against the Bolsheviks that could produce a new and more moderate Russian government.” It was, sadly, a daydream.

As the Soviets consolidated their power, Churchill took a more resigned view of toppling their regime. David Stafford suggests that Churchill began distancing himself from Reilly to keep clear of controversy surrounding the notorious Zinoviev Letter. Published in 1924 by the Daily Mail, undoubtedly with Reilly’s connivance, it called for a Marxist uprising in Britain led by communists and the Labour Party. Though it might have influenced the 1924 election, it has since been proven a forgery.

“Irrepressible Marlborough”

Reilly considered Churchill the only useful British politician in the anti-Bolshevik cause. Shortly before his death he told a friend: “Only one man is really important, and that is the irrepressible Marlborough [WSC]. I have always remained on good terms with him…. His ear would always be open to something sound.”

In June 1927 the Soviets finally announced Reilly’s fate. “One Sidney George Riley [sic], they claimed, had been caught illegally crossing the Finnish frontier. He had subsequently confessed to coming to Russia “for the special purpose of organising terrorist acts, arson and revolts….”

Backing away

By 1927 “Churchill was denying everything.” In December that year, Pepita Bobadilla Reilly appealed to Churchill for information. The reply came from his private Secretary, Eddie Marsh:

[Your letter] of the 13th December…appears to have been written under a complete misapprehension. Your husband did not go into Russia at the request of any British official, but he went there on his own private affairs. Mr. Churchill much regrets that he is unable to help you in regard to this matter, because according to the latest reports which have been made public Mr. Reilly met his death in Moscow after his arrest there.

It was “a classic letter of deniability,” writes David Stafford, “as though Churchill hardly knew who Reilly was, never mind had been a willing and active party to his anti-Bolshevik plans. Clearly he wished to keep this episode in his shadow life hidden.” Nevertheless it was a heartless letter, untypical of Churchill’s usual magnanimity. But no one, Stafford concludes, “ever had Churchill in his pocket.”

Hearts and minds

Rather than Henry Ford, Boris Savinkov would have made a more likely triumvirate with Reilly and Churchill. The evidence is that they consulted, though probably not together, and were united in their wish for a free Russia. Of the two, Churchill was clearly more taken with Savinkov. When he was arrested, tried and “confessed,” many Britons including Reilly denounced him. Not Churchill, as he wrote to Reilly himself:

I do not think you should judge Savinkov too harshly…and only those who have sustained successfully such an ordeal have a full right to pronounce censure. At any rate I shall wait to hear the end of the story before changing my view about Savinkov.[16]

He never did. In Great Contemporaries he pondered Savinkov’s fate should such a character have come from more civilized lands:

All would have been spared to him had he been born in Britain, in France, in the United States, in Scandinavia, in Switzerland. A hundred happy careers lay open. But born in Russia with such a mind and such a will, his life was a torment rising in crescendo to a death in torture. Amid these miseries, perils and crimes he displayed the wisdom of a statesman, the qualities of a commander, the courage of a hero and the endurance of a martyr.

Reilly too was born in Russia, with all that meant for own life. Yet Reilly is mentioned neither in Great Contemporaries nor The World Crisis, Churchill’s memoir of the Great War. “Like Clare Sheridan’s adventures in Moscow,” concludes David Stafford, “here was an episode of secret war that he wished to keep quiet.”