The Greatness of Alex Tremulis, Part 2: Tucker to Kaiser-Frazer

Continued from Part 1. My Alex Tremulis piece was published in full in The Automobile, March 2020.

Alex and Tucker

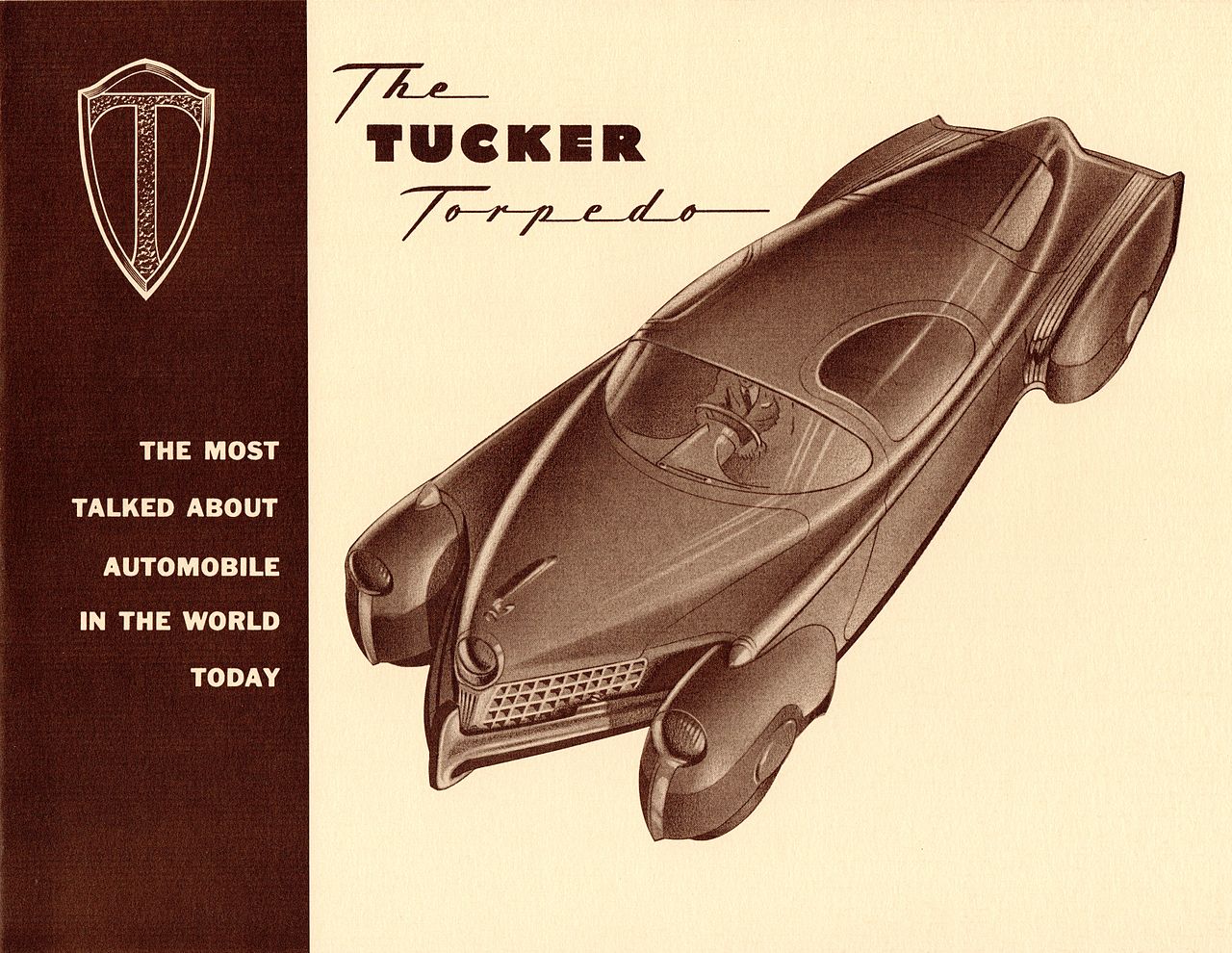

Like Bob Bourke’s famous 1953 Studebaker “Loewy coupe,” the 1948 Tucker was almost entirely the work of one designer. Of course many helped, and both Bourke and Tremulis gave them credit. But as near as one comes to designing a car by oneself, they did.

Alex set to work in a studio at Tucker’s large, ex-Dodge plant in Chicago. As chief designer he had to inject practicality into Preston Tucker’s enthusiasm. First concepts included a car with cycle fenders that turned with the wheels, a periscope rearview scanner, and vast expanses of compound-curved glass. Tremulis argued that the first two ideas were impractical. As for glass, such curvature exceeded the technology of the contemporary glass industry.

“It was hard enough,” Alex said, “to add Preston’s third central headlamp, which he wanted to turn with the wheels. Or those big doors inset into the roof—along with a rear-mounted air-cooled engine.” (Clever ideas were not always thought out: Tucker soon had to issue covers for the swivel headlamp, which tended to blind oncoming drivers on curves. And contemporary technology was not good enough to keep rain from pouring on your head when you opened one of those inset doors.)

With a stock issue pending and dealer previews set for mid-1947, it was a battle against the clock. Tremulis developed a full-size clay model, adopting bumper ideas from fellow designers. Dealers greeted a steel prototype with loud huzzahs on June 19th. Tucker dubbed it the “Tin Goose.” It looked bloomin’ marvelous! Or at least drastically different from any contemporary car.

Performance and aerodynamics

I once asked Alex for his Tucker driving impressions. “The handling, acceleration and top speed were impressive,” he said. “We always considered ten-second 0-60 times slow by about a second and a half because of the [shift] delay. Third was utterly amazing for passing, and on several occasions I reached 105 mph with it.” (Most Tuckers used Cord four-speed transmissions with the Bendix electro-vacuum shifting.)

For comparison, Tucker bought a Cadillac coupe, reputedly America’s fastest car at the time. The Cadillac, Tremulis recalled,

could reach 80 mph in 22 seconds; the Tucker was doing 80 in 15. At 22 seconds the Tucker was at 90. By the time the Cadillac reached 85 mph in our many drag races, the Tucker could hit 100. At sea level our top speed was 122 mph, though the Marquess de Portago was timed at 132 at Sebring. At Bonneville, where the altitude is 4200 feet and the air less dense, Tucker #10 was clocked on three occasions at 130 mph, in spite of loss of horsepower due to altitude.

* * *

Such numbers seem unbelievable in 130-inch wheelbase car with only 166 horsepower. The answer was quite simple, Alex explained:

I deliberately designed it to be as streamlined as possible, without being too controversial. Eighty percent of the bottom was under-panned. The rear-mounted engine also helped. A typical front engine requires an air intake area of some 250 square inches. Once trapped, the air has no place to go, except to spill out through the hood opening or underneath. The Tucker rear fender air intakes required only forty square inches of area—air entered the radiator core and exited through the rear grille. There were also little details—for example, no external rain gutters.

Good streamlining, Alex insisted, depends on details. “It all adds up.” Breathtaking, you might say in 1948. In Chicago tests, the Tucker’s coefficient of drag (CD) ranged around .30, similar to a modern car’s. This was unheard of at a time when a Lincoln CD was .55. Even the VW Beetle was .48.

Tucker: the reality

Although Tucker’s venture ended in lawsuits and bankruptcy, Alex Tremulis was blameless. (Nor will we learn much from the hagiographic film which set up Tucker as the victim of Detroit moguls. If GM really wanted to put him out of business, why did they sell him Delco electrics?) For all his engineering know-how, Preston Tucker was a smalltime promoter who didn’t know his way around business. He had no concept of the resources needed to launch a new car company.

Alex Tremulis pointed to the comparison with another new postwar car company, Kaiser-Frazer. K-F’s initial capitalization was $52 million, and it wasn’t enough. Chevrolet set aside $100 million just to redesign its 1949 models. Henry J. Kaiser later admitted, “we should have raised $200 million.” Tucker raised $15 million. (For today’s value, multiply by 11.)

Kaiser floated two stock issues, admitting in its prospectus that it was a gamble, stating what it hoped to accomplish. Tucker floated one stock issue, promising the world, and found himself in trouble with the Securities and Exchange Commission. They charged him with false statements, making indirect payments to promoters, assigning engine work to his mother’s machine shop, and other irregularities.

Significant nothwithstanding

Like Tucker, Kaiser promised things he couldn’t deliver: unit body-frame construction, torsion bar suspension, front-wheel-drive. Unlike Tucker, Kaiser quickly regrouped. He substituted a car he could deliver, which people could actually buy. Kaiser built a production line covering millions of square feet and was building 200 cars a day almost from the start. Tucker sent fifty pilot cars down a conveyor and called it a production line. Nevertheless—isn’t there always a nevertheless?—Tucker conceived and Tremulis developed one impressive motorcar. And Alex stuck it to the end, working every day, long after his paychecks stopped. Finally the plant closed and the doors locked.

Preston Tucker died in 1956, but Alex continued to toy with his ideas. In 1963 he sketched drawings for a revival Tucker called the Talisman, one of Preston’s original model names. Its coefficient of drag was .25. With radial tires and Alex’s proposed mid-mounted Oldsmobile V8, he expected it would do 150 mph. Forty years later his ideas triumphed. In 1987 the Society of Automotive Engineers honored him for “one of the significant automobiles of the past half-century.”

“A penchant for losers”

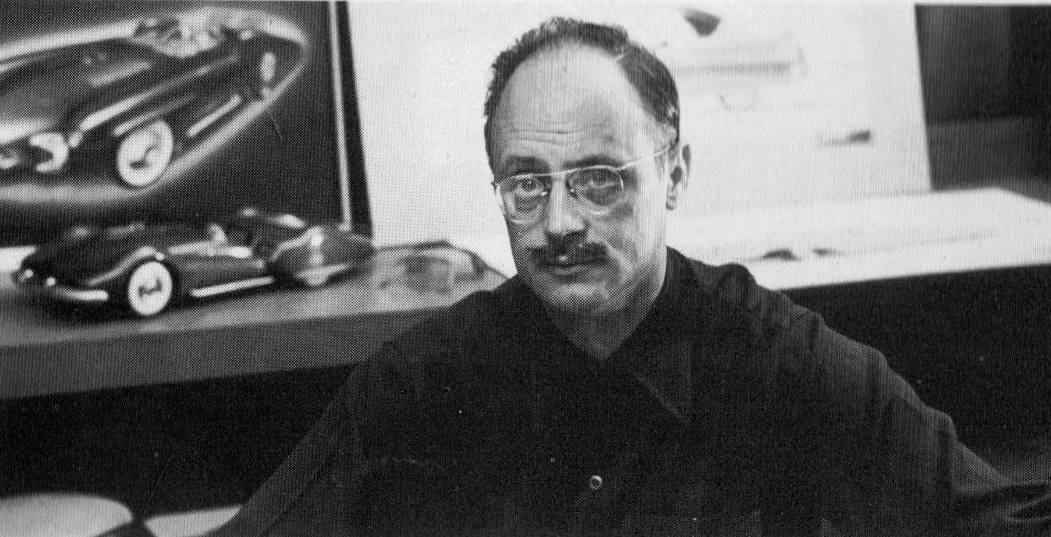

Alex engaged in MG distribution for awhile after Tucker folded, but still had a yen for design. “I guess I had a penchant for losers,” he mused. “By 1951 I was chief of Advanced Styling at Kaiser-Frazer.” They might have hired him because he showed up in a snowstorm driving a Lincoln Continental with the top down and trailing a white scarf. “I always liked to make an entrance.”

The job didn’t last long. Kaiser abandoned its Willow Run, Michigan plant in 1953 and ran a rump operation in Toledo, Ohio before expiring in 1955. But Alex enjoyed his experience, particularly the designers he worked with. In a business where egos are rampant, his generous acknowledgement of them is worth recording.

Kaiser-Frazer’s stylists

Alex called Herb Weissinger, who turned Dutch Darrin’s 1948 clay model into the ground-breaking 1951 Kaiser, “a maestro in the execution of a line on a surface. His chrome appliqués were done with the perfection of a Cellini.” Arnott “Buzz” Grisinger, Alex said, was “the greatest sculptural design modeler. A quick sketch of a beautiful car floating in space sans wheels was all he needed to attack a full-size clay model. The body engineers told me they never surface-developed any irregularities. They took templates off his clays and used the lines verbatim.” Bob Robillard “was indispensable in refining and working out the endless details for production. I best remember Bob sitting in the front seat of a prototype for weeks on end, personally modeling the instrument panel…he said that in order to design it, you have to live behind it.”

“Advanced Design” at Kaiser-Frazer sounds like an oxymoron. But in 1951 sales were up and they still thought they had a chance. The Tremulis talent for naming cars surfaced when he suggested “Sun Goddess” for a prototype hardtop Kaiser the company considered but never built. “I named it for an Egyptian gal I knew,” Alex quipped.

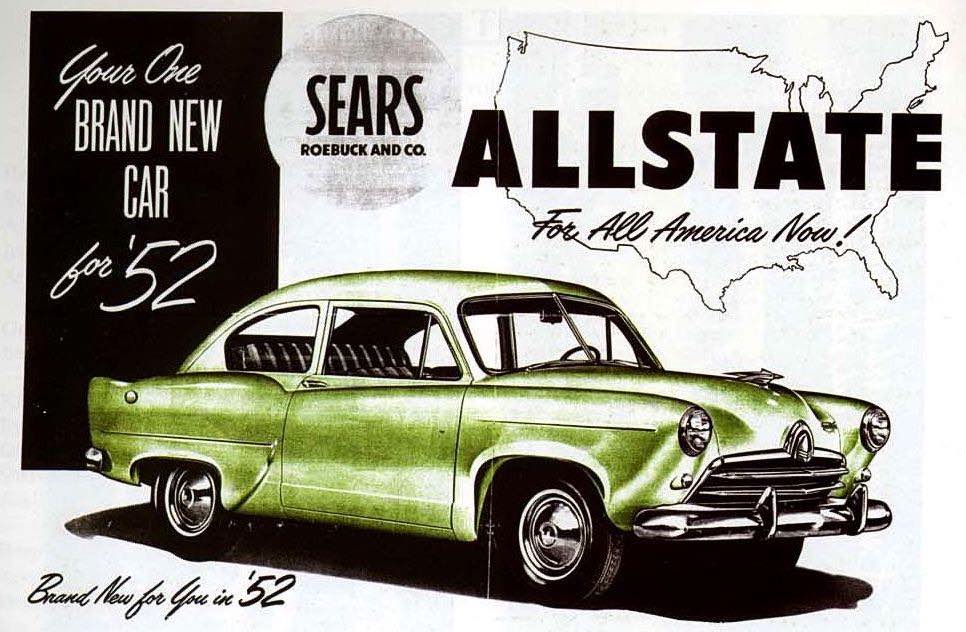

His first K-F assignment was the Allstate, a facelifted Henry J sold through Sears, Roebuck catalogues in 1952-53: “I did a hurry-up remake of the grille, putting in two horizontals and a little triangular piece, made up a jet plane type bonnet mascot and put on the Allstate logo with a map of the United States. Voila, there it was!” But he was just getting started.

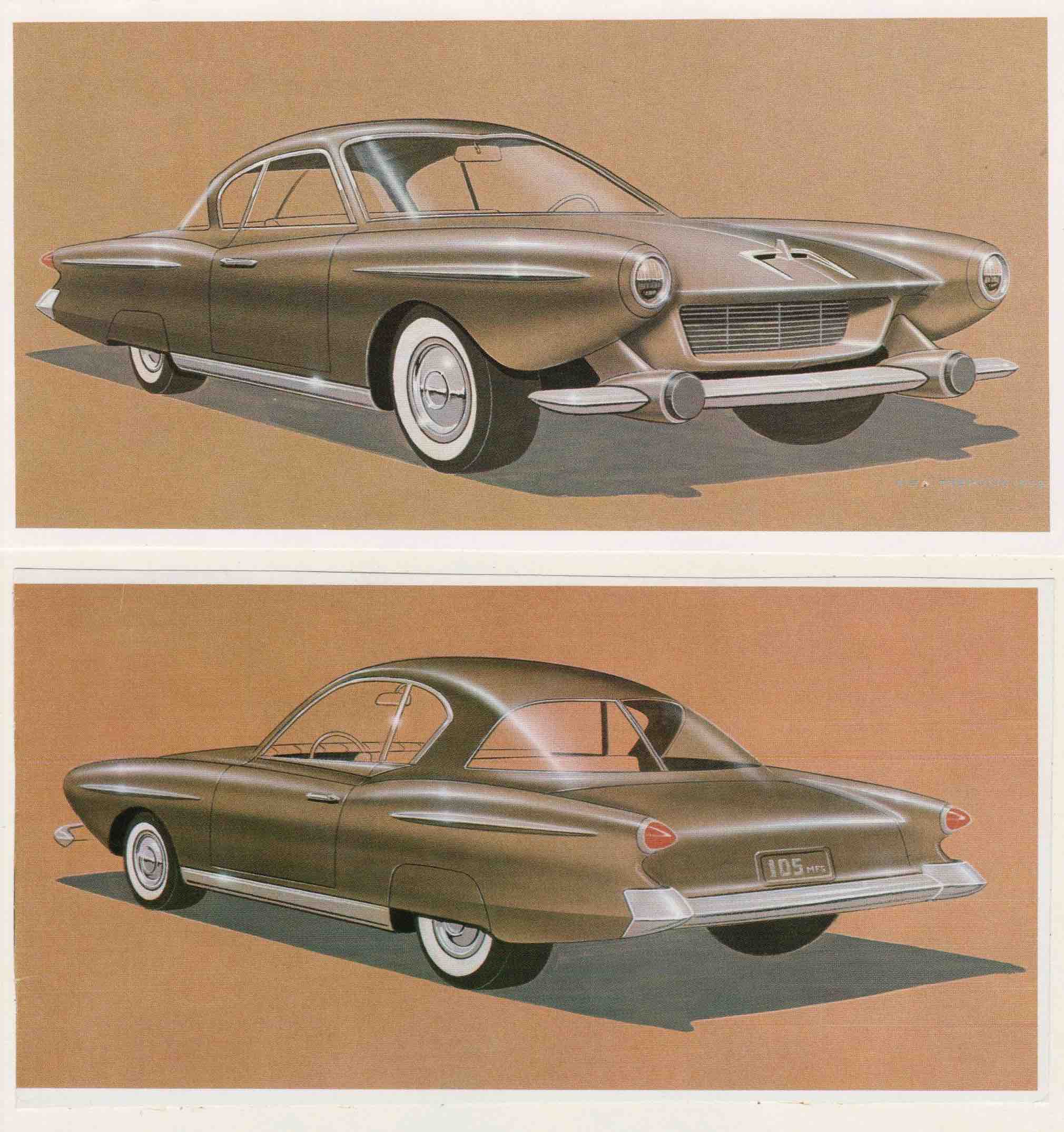

Might-have-been: the Kaiser 105

His proudest achievement was the “New Composite Body Program”: a complete restyle for the Kaiser and Henry J for 1955 or 1956—cars that never arrived. The problem was twofold. Not only did Kaiser need updated styling; they badly needed performance. But there were only underwhelming sixes and fours.

Reprising his experience at Tucker, Tremulis stressed streamlining and light weight. They slightly downsized the new Kaiser; the Henry J gained needed interior room by going from a 100- to a 105-inch wheelbase. Alex recalled:

The 105 design called for a flat four-cylinder engine coupled to front wheel drive. With its lightness [2500 pounds] and small frontal area it would perform really well. Without a change in engines, we expected 35 miles per gallon and a top speed of over 100 mph. A planned V-6 would have given greater performance. It was another Tucker, years ahead in concept and function…If the 105 had been built, I honestly believe I’d be telling a different story today.

Concluded in Part 3: “Streamlining and Speed Records”