Kaiser-Frazer and the Making of Automotive History, Part 2

Transcript of a speech to the Kaiser-Frazer Owners Club, 30 July 2015. Continued from Part 1.

Delving in

While I received no extra pay for writing the Kaiser-Frazer book, I did have the use of an expense account for travel. That was where Bill Tilden came through again. He helped me track down and interview many of people responsible for the cars Kaiser-Frazer built. Others were located through the deep tentacles of Automobile Quarterly, its contacts in the industry. We also searched for archives large and small.

Our greatest archival find was at Kaiser Industries in Oakland, California: the Kaiser-Frazer photo files, placed on loan for AQ’s use. They documented virtually every design drawing, clay model and prototype the company built.

Our greatest archival find was at Kaiser Industries in Oakland, California: the Kaiser-Frazer photo files, placed on loan for AQ’s use. They documented virtually every design drawing, clay model and prototype the company built.

Bill and I pored over them for several days, bleary-eyed as the secrets of the company came to life. Fortunately we were able to reproduce many in the book.

There were so many, it was hard to choose. Toward the end of the second day I picked a photo up, saying, “Ever see one like that before?” And Bill said, “I think we’ve seen a dozen like that, but let’s use it. It has a good looking tailpipe.” Later the archive disappeared. I don’t know if it ever resurfaced. I hope it’s in good hands.

“You know,” I said to Bill after Oakland, “this is going to be one helluva book. We’ve found this massive archive, and all these people to interview. All concentrated within ten years. I have a chance to go into far more detail than if I were writing a history of, say, General Motors.” So it proved.

Kaiser-Frazer people

As historians (as we optimistically called ourselves) we were just in time. Many of the principals, including Henry J. Kaiser, were dead. His son Edgar didn’t want to go on record, though fortunately other Kaiser people did. Many were aging or infirm, but happy to reminisce. The book made good its claim to be “An Intimate Behind the Scenes Study of the Postwar American Car Industry,” because we were able to locate and talk to so many key people.

One night in south Georgia we found Henry C. McCaslin, chief engineer of the stillborn front-wheel-drive Kaiser. Mac drank too much early in life and wasn’t long for this world. He told us what he knew, testifying to Henry Kaiser’s zest for clean-slate thinking. “I loved that old guy,” he said.

Mac was sad that the front-wheel-drive car Kaiser wanted to build didn’t work out. “We built two prototypes,” he said. (I have since heard the figure six, but Mac was there at the time; none has ever surfaced.) “But Henry and Joe Frazer needed production more than innovation. So they spent their money gearing up Willow Run.”

Willow Run was Henry Ford’s immense ex-bomber factory outside of Detroit. It was a mile long—at the time the longest car plant under one roof. Hickman Price signed the lease in 1945. Later, Kaiser-Frazer bought it from the War Assets Administration. Just two years later, K-F was the leading independent car producer—out-producing Studebaker, Nash, Packard, Hudson and Willys.

K-F’s inspired engineers

We were lucky to find Ralph Isbrandt, chief engineer on the groundbreaking ’51 Kaiser project. The poor guy was dying of cancer, but he spent many hours with me and was a leading source of engineering background.

Ralph was hired in 1948 by Kaiser’s engineering vice-president Dean Hammond, who told him to ignore the organization chart and deal with him direct. “Hammond was not one of the Kaisers’ California ‘orange juicers’ we Detroit hands joked about,” Ralph remembered. “He had a good staff…

“John Widman was chief body engineer—his father had founded the Widman Body Company, later bought by Briggs. He had the idea for the ultra-thin A-pillars, created by turning them on their sides. The experimental engineers were West coast guys, George Harbert and Ben Edmonston. Frazer recruits were George Henry, later motor engineer for American Motors; and Les Klauser from Chrysler, who ran K-F’s engine factory.” It was a true team effort, Detroit and California guys, Isbrandt told me. “If only the two sides had maintained that relationship, things might have been different.”

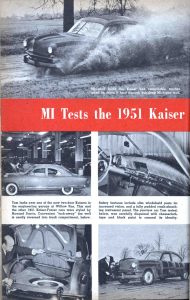

Roadability in the Fifties

From early 1948, the engineers turned entirely to an all-new ‘51 Kaiser. Isbrandt continued:

We wanted a low center of gravity and a unit body. We took a Nash apart, but decided that Nash had just put a conventional frame on a standard body. John Widman said we could get close to unitized construction in stiffness and rigidity.

That’s why we used a great many body mounts, each carefully located. The result was an extremely rigid car, yet a conventional body and frame, easier to work on, less susceptible to rust. Our production prototype weighed only 3200 pounds. Nobody in the industry was within 400 pounds of us.

Ralph bundled Tom McCahill, the colorful Mechanix Illustrated road tester, into a pre-production prototype. They drove out on the Willow Run airport runway—in between planes taking off! That was their “test track” in those days.

Ralph wound the car up to 60 and threw the wheel hard over. It skidded but remained flat and controllable. “I scared the hell out of him,” Ralph laughed. “He nearly jumped out! But I knew what this car could do.” If only they’d made a V-8, to go with that fine handling.

Uncle Tom had a way with words. He wasn’t big on Kaiser’s compact, the Henry J: “It looks like a Cadillac that started smoking too young.”

But he loved the ’51 Kaiser. “It has more creative thinking since Gen. Grant got his last shave.” Of the ’53 Manhattan he wrote, “It rides like a wheelchair upholstered in cream puffs.”

So if and when you see one of those Kaisers on the road, think about Ralph and George and John and Dean and Les and Ben, who together engineered one of the best handling full-size American cars of its day.

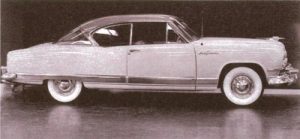

K-F’s fabulous styling

Of course the thing that attracts us to these cars is not so much under the skin but their styling, so far ahead of its time. That began, as so many things did, with Dutch Darrin. Without Dutch, they wouldn’t have been the same. But without the team, the cars might never have been as good as they were. The ’51 and its successors were testimony to talent and teamwork. (For the complete design story, see “Kaiser Capers, Part 3.”)

Dutch was a visionary, a romantic, very much his own man, not inclined to tolerate the ideas of others. He was utterly unable hide his light under a bushel. Joe Frazer had hired him to design the first generation cars of 1947-50.

When he heard a redesign was afoot Dutch rushed to Willow Run. There, at a famous review, Henry Kaiser personally chose Dutch’s full-size airbrush rendering, the “Constellation,” over competing designs by his own stylists and Brooks Stevens Associates.

Brooks Stevens, the other outsider, had a distinguished history in industrial design successes, from Miller beer bottles to the civilian Jeeps. Although his basic shape was not chosen, he contributed many detail ideas, including the idea of a “wrap-around bumper” and a combination bumper-grille. (I called Brooks, to his great delight, “The Seer Who Made Milwaukee famous.“)

Duncan McRae, who was Dutch’s assistant then, told me of the famous design review:

The other designers lined up in front of our drawing, hoping Mr. Kaiser wouldn’t see it. Dutch was infuriated. “Watch this,” he said. Then he loosened his belt, got up, called for both Henry and Edgar Kaiser, and as he walked towards them his pants fell to the floor.

After the laughter subsided, he held their complete attention. And of course he did a beautiful selling job. Minutes later, Mr. Kaiser said, “Well, this is it!” Seems incredible by today’s standards, but that’s how cars were shaped in the Fifties.

Devils in the details

Once a design has been accepted, it has to be made into a viable production car. That always involves compromises, and Dutch was no diplomat. So in assigning credit for the ’51 Kaiser, we have to acknowledge all those who followed Dutch and saw it into production.

Alex Tremulis, who had designed the Tucker, headed K-F Advanced Styling, It was he who styled a hardtop prototype which he called the Sun Goddess, “after an Egyptian gal I used to know.” Alex told me about the company’s great in-house designers:

Herb Weissinger, who developed the production shape, was one of the most talented in the profession: a maestro in the execution of a line on a surface. His chrome appliqués were done with the perfection of a Cellini. He never received the plaudits of his profession, but he was one of the greatest.

Arnott “Buzz” Grisinger was the greatest sculptural design modeler I ever met. He did little on paper, usually a quick sketch of a beautiful car floating in space without wheels. This was all he needed to attack a full-size clay model. A master of simplicity, his models were examples of sheer elegance. Engineering draftsmen told me they never had to surface-develop any irregularities. They just took templates off the clay and used the lines verbatim.

Bob Robillard, “Robillardo,” was indispensable when it came to refining and working out endless details for production. Like Buzz he was happiest working alone. I remember Bob sitting in the front seat of a Kaiser sedan for weeks on end, personally modeling the ’54 instrument panel. A real purist, he said that in order properly to design it, one had to live behind it. He was worth ten of his peers.

Team effort

Duncan McRae and Herb Weissinger were mainly responsible for finalizing the ’51 Kaiser. Poor Dutch was eternally frustrated, and eventually left, and the company ungratefully took his name off the cars in 1952.

“I remember coming into the studio one morning after Dutch had walked out,” said Bob Robillard. And there was his beautiful clay model, with a sculpting tool buried to the hilt in the hood. You could have entitled the scene ‘Frustration.’”

We don’t want to under-credit any of these people, because they were a team. And look at what they gave us. The ’51-’55 cars were lower, with more glass, than any Detroit cars on the road—the work of Dutch, Brooks, Herb and Dunc. Grisinger styled the famous 1954 facelift, Bob Robillard did the instrument panels. Carleton Spencer gave us the Kaiser Dragons, and a host of fabrics and colors never seen in cars before. The entire industry benefitted from their work.

In life, nature and nurture do not suffice…

…Success requires they be joined, and their convergence is due to a third ingredient called luck. That is, being in the right place at the right time. Kaiser-Frazer was supremely lucky to have arrived when it did, and to recruit such supremely talented people. One of the most charming things about them, from Joe Frazer down to the lowest engineer on the totem pole, is that they never stopped saying so.

Kaiser-Frazer’s achievement, then, was not just the compulsive application of massive talent, but of a series of events at a unique time. “Luck” means the innumerable things that happen which initially have little to do with talent or striving. In other words, we are fascinated by the K-F phenomenon in part because it is filled with incidents that, were they part of a novel, would cause disbelievers to dismiss them as poetic license.

A story like a novel

Imagine, then, a novel about a fictional company called Kaiser-Frazer. Its story of course must be ten years long—what used to be called a Victorian triple-decker. Indeed, the first melodramatic detail that strikes the reader is just how long it lasted.

It faced truly formidable odds: the combined might of a major industry during the greatest period of economic expansion in American history. Except that it was not a novel. It was the Last Onslaught on Detroit.

One thought on “Kaiser-Frazer and the Making of Automotive History, Part 2”

If anyone wants to know about Kaiser-Frazer & Jeep this is The Best Book by Richard Langworth.

Richard touches All Bases of The Subject like All of His other Books. You can go back for a Refresh Reference on any Subject.

G B Bonham

Comments are closed.