“Too Easy to Be Good”: The Churchill Marriage and Lady Castlerosse

My article, “The Churchill Marriage and Lady Castlerosse” was first published by The American Spectator on 13 March 2018.

“Here Firm, Though All Be Drifting” —WSC

It’s all over the Internet, so it must be true. Not only did Winston Churchill oppose women’s rights, gas tribesmen, starve Indians, firebomb Dresden, nurse anti-Semitism and wish to nuke Moscow. He even cheated on his wife—in a four-year affair with Doris Delevingne, Viscountess Castlerosse.

So declare the authors of “Sir John Colville, Churchillian Networks, and the ‘Castlerosse Affair’”—unreservedly repeated by British television, multiple media, even a university: (“Winston Churchill’s affair revealed by forgotten testimony.”)

All these fables—every one demolished by serious inquiry—are commonplace today. As Secretary of State Cordell Hull observed: “A lie will gallop halfway round the world before the truth has time to pull its breeches on.”

Why is “Churchill’s Secret Affair” (the television title) important? Who cares? It matters because the Churchill marriage was admirable and historically significant. Winston Churchill would have saved liberty without his wife Clementine, if not quite as effectively. Shucks, calling him a mass murderer is easy. But if you’re going to besmirch his marriage, you need to present facts.

Castlerosse or Elliott?

“The Castlerosse Affair” declares that Churchill’s philandering, “hidden until now, was something in the nature of a bombshell.” It was neither hidden nor a bombshell. Rumors of it have been around ninety years—with conflicting dates and two different women.

Late in his life I came to know Henry Thynne, 6th Marquess of Bath, a Churchill admirer and collector. He told me that Sir Winston, famously loyal to Clementine, had “strayed only once”—with the American actress Maxine Elliott. Elliott was a lifelong friend, whom Churchill visited at her Riviera villa, Chateau d’Horizon, in the 1930s. She was then in her seventies, but Lord Bath placed the affair twenty years before that. He could offer no proof, save his own circle of friends. Was there anyone beside Maxine? I asked him. “Not that I ever heard of.”

Ironically, Doris, Lady Castlerosse, was also a friend of Elliott’s. Indeed, according to the authors, her affair with Churchill took place in 1933-36, at Chateau d’Horizon.

Gossip about l’amour between Churchill and Castlerosse actually began five years earlier. The rumor’s ephemeral nature is suggested by the first alleged encounter—at the Paris Ritz in 1928. Four years later Doris, a notorious courtesan, apparently did sleep with Churchill’s son Randolph. The story goes that when her husband rang him saying, “I hear you are living with my wife,” Randolph replied: “Yes, I am; and it’s more than you have the courtesy to do.”

The only source for that quote is John Pearson’s Citadel of the Heart, a scathing tell-all about the Churchill family. Yet even Pearson, who omitted no scandal, dismissed the idea of a Castlerosse affair with Randolph’s father: “As with so many rumours of this sort, it is unprovable either way.”

Sir John Colville

Now the Castlerosse story is back, with an apparently solid source: Churchill’s longtime private secretary. In a 1985 interview with the Churchill Archives Centre, Sir John “Jock” Colville disclosed the “evidence,” which we are told no-one previously listened to. (This is inaccurate; other historians had heard it, but dismissed it as unprovable.)

Colville said he was having tea with Winston and Clementine when literary assistant Denis Kelly approached with what Colville said were love letters from Castlerosse. “Clementine read the correspondence and went pale,” the article states. “She had never previously thought that Winston had been unfaithful….she was frightfully anxious about it for months….Colville, in response, tried to play it down….” (Actually, Colville says he told her, “I bet he didn’t,” in effect contradicting himself.)

All this begs a rather obvious question: What was Sir Winston’s reaction? After all, Colville says, he was right there. Did he admit his sin and ask forgiveness? Hotly deny it? Would a man revealed to his wife as a philanderer say nothing? Neither Colville nor the authors tell us.

* * *

In the 1980s I had several conversations with Jock Colville, whom I loved and respected as a “keeper of the flame.” I do not pretend they were of any great importance, but we did discuss Lord Bath’s belief in Churchill’s affair with Maxine Elliott. Sir John labeled this ridiculous. He did not refer to Castlerosse. Of course, that is hardly dispositive.

Moreover, Colville did not even meet Churchill until 1940, years after the supposed indiscretions. The best “The Castlerosse Affair” can offer is that “he believed it” and “would not have made the allegation lightly.” In my experience he was not above repeating chatter among his social set. Before the Kelly episode, that is the only way he could have heard about it.

And that is how everybody heard about it. The television program is replete with family tittle-tattle: “It was known….a tradition in our family….my mother told me.” Decades ago, biographer George Malcolm Thomson speculated that the couple “may have enjoyed a ‘romantic friendship.’” In 2016 (well before the current article) Lyndsy Spence, Castlerosse’s biographer, cited “much repeated gossip,” citing Pearson. “On the face of it,” the authors state, “Pearson’s and Spence’s claims do not look well supported.” But Pearson did not make the claim—he denied it. Still they insist that “Colville’s claim of an affair was, at least, plausible.”

Denis Kelly

The only real evidence Colville offered was the Kelly episode, but “The Castlerosse Affair” doesn’t tell us what Kelly thought. As it happens, he thought a great deal.

I knew Denis Kelly well, corresponded with him, and published an imaginative article of his about conversing with the ghost of Sir Winston. He was a dear man, a gifted barrister. In 1947-57 he’d worked at Chartwell, Churchill’s home, sorting out the muniment room for his official biography—“to make Cosmos out of Chaos,” as Churchill put it.

Like Colville, Kelly laughed off the Maxine Elliott story, saying it wasn’t the boss he’d known. “Of course,” he said honestly, “that was long before my time.” To the best of his belief, Sir Winston had never been unfaithful (Churchill Archive Centre, file CHOH 1/DEKE). If, per Colville, he had handed Lady Churchill “love letters,” he therefore had no inkling of their content—which sounds nothing like the Denis Kelly I knew.

Documentary evidence?

Surviving Churchill-Castlerosse correspondence cannot be described as “love letters.” Most of it comprises the bread and butter notes people wrote in those days—how nice to see you, will you be back next season, you were “a ray of sunshine around the swimming pool.” At the same time, Churchill was writing lovingly to his wife, describing his days at Maxine’s and everyone present, including Castlerosse—not the letters of a cheater.

“The Castlerosse Affair” tries to make the most of them anyway. In 1937, Doris wrote Churchill: “I should like to see you. I am not dangerous anymore.” This, we are told, “could be read as an indication that the affair was now over, and that Doris did not mean to try to revive it.” She was referring to her divorce, but it could equally be read that she was over a case of ’flu. In it she provides Winston with her London telephone. This has to be the first time in history of affairs that the philanderer did not have his mistress’s phone number.

The authors say Colville “implied” that the really incriminating “love letters” were destroyed, “presumably by Clementine.” True, she was not above destroying offensive material—for example, she burned the appalling portrait presented by Parliament on Sir Winston’s eightieth birthday. I guess she overlooked the “I am not dangerous” letter. But let’s assume she destroyed the rest. Why then did she include a Churchill portrait of Doris Castlerosse among the paintings she set out for display at Chartwell by the National Trust after Sir Winston’s death? (It’s still there.)

* * *

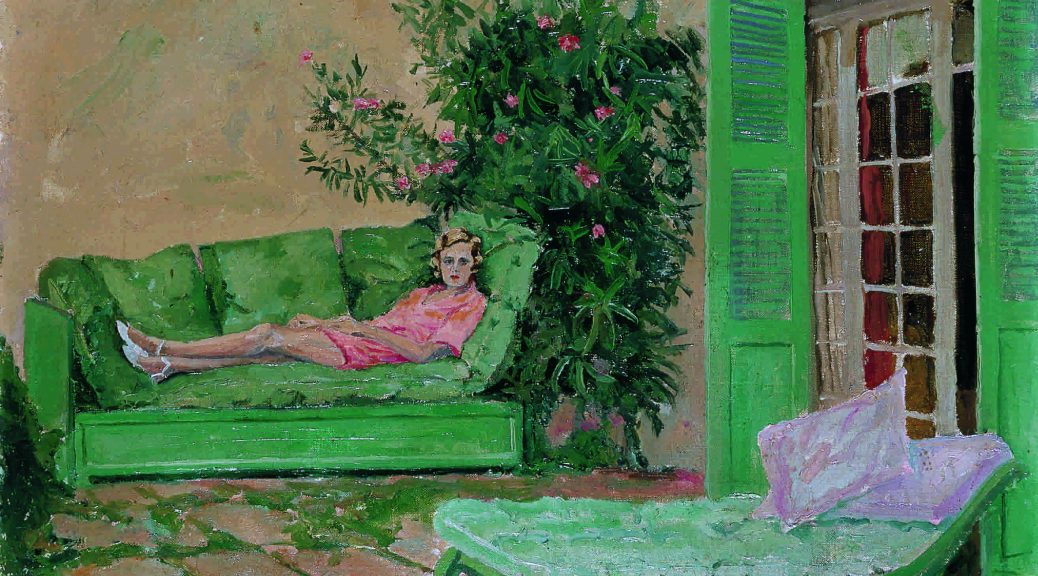

We are told that the lovestruck Churchill painted Doris four times, and that she owned two. Historian Andrew Roberts writes that he also painted Sir Walter Sickert’s and Sir John Lavery’s wives, Arthur Balfour’s niece, his sister-in-law, his secretary, his wife’s cousin, and Lady Kitty Somerset: “There is no suggestion he was sleeping with any of them. Meanwhile, he painted his wife Clementine three times.”

Ah, but none of those paintings were as sultry as that of a recumbent Doris, wearing shorts, which is supposed to be revealing. Everybody wore shorts on the Riviera in the 1930s. Yet on television a royal biographer says: “She’s lying down, so they’re halfway there.” Can these people be serious?

* * *

In 1942, years after the apparent affair apparently ended, Doris was in New York, appealing to Churchill to help her return to London. This he did. He often performed kindnesses for friends, but this, we are told, was crucial: It “could be taken to imply that Doris tried to blackmail Churchill with the portraits.” Furthermore, Churchill allegedly tried to get the paintings back.

After Lady Castlerosse died in December 1942, the paintings “ended up for a time” with newspaper magnate Lord Beaverbrook. The television show calls him “Churchill’s political fixer.” More precisely he was a sometime friend and part-time nemesis. After the war, they returned to her family. Which again proves nothing.

Where is the “sultry” painting today? To my amusement, I tracked it to Longleat, home of the late 6th Marquess, who told me the Maxine Elliot story. There is humorous irony in the wriggles and windings of this shaggy dog story.

Retaliatory sex?

“The Castlerosse Affair” also suggests that Clementine herself was unfaithful. “On the long cruise which she took without Winston in 1935, Clementine ‘fell romantically in love’ with one of her fellow voyagers, Terence Philip. Whereas it seems doubtful that she was reacting to knowledge of an affair between Winston and Doris, the episode could be taken as indicative of a coolness in the Churchill marriage at this time.” It certainly does seem doubtful—if she knew about it in 1935, she could not have “gone pale” when confronted by the “love letters” two decades later.

In the television program a Clementine biographer claims that their “marriage was on the rocks” at the time. (It omits to note the same biographer’s denials of both Clementine’s and Winston’s affairs.) Reality check: Terence Philip was a personable, socially useful art dealer, often entrusted to accompany unescorted women. Lady Soames, Clementine’s daughter and best biographer, told me her mother never gave reason to believe Philip was more than Clementine’s affectionate companion.

“Too easy to be good”

At the time of the “Castlerosse affair,” when Churchill was desperately warning of the Nazi threat, the French Ambassador suggested that Britain and France join with Hitler in a war against European communism. Churchill’s reply to that ill-considered proposal precisely applies to this farrago of innuendo: “Too easy to be good.”

Why do we continually encounter character assaults on figures most of the world reveres? It stems from a skewed vision of the egalitarian principle, the theory that there are no great figures, we are all the same. The scholar Harry Jaffa cited a public appetite for books and articles “which denigrate nobility or idealism. Politics as a vocation is today in bad repute. Young people are led to believe that to succeed is to prove oneself a clever or lucky scoundrel. The detraction of the great has become a passion for those who cannot suffer greatness, and will not have it believed.”

The single remark of an old colleague, honorable though he was, is contradicted by other old colleagues, the actions of Churchill’s wife and friends, lack of facts, and plain common sense. The Churchill marriage remains undiminished, as it should: a tribute to a historic partnership. As Churchill was wont to remark of his fifty-seven-year union: “Here firm, though all be drifting.”

2 thoughts on ““Too Easy to Be Good”: The Churchill Marriage and Lady Castlerosse”

Thanks for standing up for the truth.

Thank you for posting this. I was in contact with the research assistant for Churchill’s Secret Affair (originally titled Churchill’s Secret Mistress) and I have to say I found the overall research to be shoddy. I offered insightful anecdotes regarding the ‘affair’ (which I dismissed) but that doesn’t make good TV, does it? You might find my blog useful: https://themitfordsociety.wordpress.com/2018/03/05/churchills-secret-affair-or-how-the-evidence-was-misrepresented/

Comments are closed.