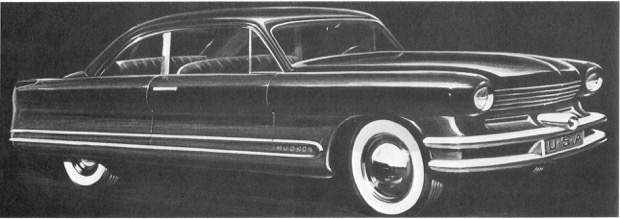

Should this have been the “Step-down” Hudson?

Reader Brent Hinde writes about my Hudson book, The Classic Postwar Years (1977, reprinted 1993). Very kind of him, since it’s the first mention of that book in decades.

Recently at an estate sale I picked up the book and found it an excellent read. On page 38 is a terrific sketch of a car that should have been built, rather than the design management chose. My question is: Who drew that sketch? Are there more drawings like that in existence? It would make a great guide for a project car.

Hudson’s styling team

The drawing (top) shows a crisper shape than the production 1948 Hudson. It was one of many Hudson styling proposals. Compared to the car they actually built, it looks more modern. There’s a one-piece curved windshield, and the tail end is squared off rather than tapered. But I can’t say who the artist was because the Hudson styling team was large—and impressive. It was typical of the kind of diverse groups that inhabited styling studios in an age when cars were shaped by people, rather than computers.

Styling at Hudson was then under famous Design Director Frank Spring. He had conceived the basic package as early as 1941. Later Spring would produce the compact Hudson Jet and the radical Hudson Italia. Chief of Design under Spring was Art Kibiger, who later helped conceive of the Aero-Willys. There was Robert F. Andrews, who would be involved in the Studebaker Avanti for Raymond Loewy. Strother McMinn would become a noted design instructor and automotive writer.

Hudson Characters

Dick Caleal and Bob Koto were Hudson stylists who would later contribute to the famous 1949 Ford. (Caleal, nicknamed “the Persian Rug Salesman,” baked the small clay model of the ’49 in his wife’s oven before presenting it to George Walker at Ford.) Art Fitzpatrick was later associated with Dutch Darrin and Pontiac. Hudson also had Arnold Yonkers (artist), Arthur Michael (modeler) and Bill Kirby, a balding hippie. Kirby was a scruffy idea man who always looked like he’d just emerged from a wastepaper basket. Yonkers, an affable Dutchman, was a part-time minister. These were the kinds of individuals who designed cars in those days. They were the reason cars then looked so different from each other.

Alas Hudson destroyed most of its images of styling proposals and clay models once a car was built, and the only ones I could find were loaned by the above people for my book. The one you like bears no signature, so we can’t pin it down. It is not Bob Andrews’ work; his style was different, and he usually signed his drawings “RFA,” like the one shown here.

Ideas for the “Step-down”

What both these sketches illustrate are the ideas Kibiger and Andrews were promoting: tubular bumpers, a high-mounted grille and fenders almost flush with the hoodline. Raising the front fenders was a radical idea in 1946, when the ’48 Hudson was designed. They didn’t reach the hood level on a production car until the 1951 Packard.

Kibiger and Andrews joined Willys before the new Hudson was finished. But they drove up from Toledo to attend its debut at the Masonic Temple in Detroit. “The workmanship surprised me,” Bob Andrews said. “It looked great. And it seemed as though the new Hudson was going to create quite a splash….all of the frustrations of the last few years were eased. This was my first experience at milling through crowds who were applauding something I had been a part of.”

Not easy to change…

The Step-down Hudson was so-named because you stepped down into it. The floor sat low between the frame rails, permitting dramatic lowness. It was, for example, seven inches lower than the 1948 Buick. The problem was that it was hard to modify. Hudson had to stick with this basic shape through 1954. In those years, the public expected a new style every twelve months. This hurt and ultimately crippled the company as an independent producer of automobiles. Nevertheless, the low center of gravity made for a roadable car that held the NASCAR manufacturer’s championship for 1952-54—powered by a six-cylinder engine at that.

2 thoughts on “Should this have been the “Step-down” Hudson?”

Richard, I have your book and love it. Thank you! Regarding the Hudson that Mr. Hinde likes, I agree. Being more “3-box” in proportion it likely would have had more staying power. The sedan that management chose had dated “2-1/2 box” proportions with rear wheels too far back relative to rear doors , and deck and rear overhang too short. There is no doubt that Monobilt’s many attributes helped sell Hudsons in these years. Had the cars looked better from Day 1, Hudson might have enjoyed strong sales with minimal appearance changes for a full 6 year cycle, replaced in 1954 instead of creating the Jet, and perhaps shared with Packard… the “Master Engine Builder” joining forces with the “Master Body Builder” to achieve economies of scale. Regarding the competition, while it is true that car makers at that time changed the front and rear “6 inches” frequently, they did not change the basic body every year. Cadillac’s shortest “major” was 48-49, then they went a full 4 years with the same design, then 3. It wasn’t until 1957 that they went on a 2 year cycle, extending it to 3 during the Seventies and even longer after that.

Judy Kambestad writes: “Classic Car’s (September 2017) Hudson article discusses the demise of AMC, successor to Hudson. I had forgotten how colorful cars were in the Fifties. The 1957 Hornet V-8 Hollywood hardtop was a beauty. (My father liked the hardtops but in General Motors’ models.)”

Those Nash-bodied, last-gasp big Hudsons (1955-57) were some showboats. I wanted my Dad to buy a ’55, but he said it was going to be an orphan. So he bought a DeSoto….

Comments are closed.