The Tucker Story (No, It Wasn’t the Car to Beat Detroit)

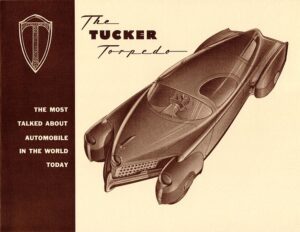

Tucker, “the First Completely New Car in Fifty Years,” was announced in 1946. To a war-weary yet optimistic America, it seemed to be tomorrow’s car today.

The Tucker was a dramatic break with tradition. Its engine was a 166 horsepower flat opposed aluminum six, rear-mounted for optimum weight distribution. Its frame was lower than the centerline of the wheels. Suspension was fully independent. The ratio of pounds to horsepower was lower than any previous American car. Top speed was said to be 120 mph.

Other imaginative features included a “cyclops” center headlight that swung with the front wheels, a protrusion-free dashboard, and a ”storm cellar” compartment into which the front seat occupants were supposed to dive in the event of collision. The doors were cut into the roof for ease of entry. Individual glove boxes were in the door panels. A “pop-out” windshield ejected in a crash.

Tucker styling, by Alex Tremulis, was arresting, and the car was supposed to sell for under $2500. All this was mind-boggling to people for whom the newest cars were the 1947 Kaiser, Frazer and Studebaker—which, though freshly styled, were entirely conventional under the skin.

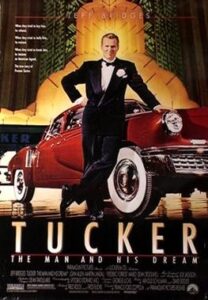

Francis Coppola’s 1988 film Tucker: The Man and His Dream, starring Jeff Bridges, colorfully recounts the story. But it tends to cast Preston Tucker himself as the victim of a cabal led by rival manufacturers and the politicians in their pockets.

Francis Coppola’s 1988 film Tucker: The Man and His Dream, starring Jeff Bridges, colorfully recounts the story. But it tends to cast Preston Tucker himself as the victim of a cabal led by rival manufacturers and the politicians in their pockets.

There is no doubt that certain Michigan politicians looked askance at Tucker. Alas Preston himself made promises he couldn’t keep. While Studebaker and Kaiser-Frazer built millions of cars, Tucker built only 51. By 1950 his enterprise had dissolved under charges of fraud, and the trial of Preston and seven of his colleagues.

Tucker redux

For awhile it looked like Tucker was going to set the industry on its ear. He rented the largest plant under one roof in the world, sold $15 million worth of stock, and built prototypes which performed impressively well.

But as a serious mass-production car, the Tucker was dead on arrival, from the standpoints of both cost and its quirky features. Illustrative of these problems is the story of Tucker engine development.

The first Tucker engine was a huge 589, installed only in the prototype or “Tin Goose.” Starting it required 30 to 60 volts of external power. It had other problems, according to Richard E. Jones, writing in The Milestone Car: “No satisfactory hydraulic valve actuating system or practical fuel injection were developed.”

Preston Tucker continued to promise fuel injection, but the necessary level of performance was never met. Ex-Cell-O fuel injection was tried, but in February 1948, Tucker asked his engineers to test their engine with a carburetor, because “considerable work was still required on the injector.”

It took another decade for General Motors to get fuel injection to work reliably (sort of). Yet the decision to postpone fuel injection occurred months before Preston promised that his car would have it.

Bust upon bust

Finally, Tucker opted for the famous Aircooled Motors 335 cid six. From it, he promised 275 horsepower and speeds up to 150 mph. Did its price reflect reality? Richard Jones wrote: “The average cost of the ninety-one engines delivered through the end of August 1948 was $1418 each. And this was exclusive of $128,000 expended by Aircooled for engineering, tooling and development work.” Subtracting $1418 from the projected price of $2450 leaves $1032 for the rest of the car. Retail. Out of that, Tucker promised to wring features like the swiveling third headlamp, disc brakes, seatbelts, independent suspension, etc., etc.

Tucker realized the impractical cost of the 335 engine when, in August 1948, David Doman was assigned to create a cheaper alternative, the “335U.” The dreamlike quality of the Tucker episode is nowhere better illustrated than by Doman’s brief: The new engine must pack the same horsepower and displacement, but cost a third less.

Doman tried, using a two-piece crank and cylinder block and two heads covering three cylinders each. But there was never any sign that the 335U could meet the boss’s requirements. Preston then ordered another 125 of the original 335 (at $1500 each).

Richard Jones correctly summarizes the 335 as fitted to the fifty “production” cars: “[O]ne of the most impressive automobile engines of that day or this, [whose] quality and aircraft standards precluded mass production.”

On the road

There are similar things to say about the rest of the Tucker drivetrain. Former GM president Ed Cole, interviewed by Michael Lamm in 1973, mentioned Tucker’s first configuration of “driving the rear wheels with a pair of converters, and transmitting axle torque through a converter.” Tucker had to abandon that. John R. Bond of Road & Track, in another interview, said: “…you had all that weight out back and a pretty long wheelbase…the handling was catastrophic.”

Most of those who have driven a Tucker agree that, like the early Corvair, it’s perfectly safe, provided you are competent to handle drastic oversteer. We all know what happened to Corvair owners who could not. Some sued General Motors.

Things about the Tucker that first looked good did not bear up in practice. The famous swiveling center headlamp was itself a compromise. Tucker originally wanted a fixed center headlamp and the flanking lamps turning—along with the front fender assemblies. Tucker designer Alex Tremulis talked him out of that—what professional wouldn’t? But the center swivel-light would itself have been banned as a hazard to navigation, frying the eyeballs of oncoming drivers at the apex of every curve.

Bright ideas, unintended consequences

There were the novel Tucker doors, cut into the roof for easy of entry and egress. But there were no rain gutters, and in a downpour they bid fair to soak the hapless passenger.

There was the “storm cellar” compartment ahead of the seats, which Tucker said one could “drop into” during a crash—as if you’d have that kind of time.

The “storm cellar” seems to have been a fallback safety position. Tucker wanted seatbelts, but staffers convinced him they would imply, at that time, an unsafe car. (They did exactly that when Nash briefly offered them as a 1950 option.)

The movie depicts Tuckers with modern metal-to-metal seatbelts. If ever installed they would have been the contemporary fabric-to-metal type. But, like the disc brakes he also vainly promised, seatbelts seem to have been forgotten by the time Tucker framed his final promotion.

It’s too bad. Many of the concepts were novel, interesting and good. It had a remarkably low drag coefficient (though I can scarcely believe the claim of .30). Tucker’s elegant lowness, lightweight rear engine, and safety features however crude were all commendable.

But Preston Tucker lacked the business acumen to find sufficient time and money for their development. To dub him, as the film does, a genius thwarted in a willful conspiracy led by Detroit—whose main problem in those days was to get enough steel to build leftover prewar designs—is to fantasize.

Business models compared

Compare Tucker with the other major postwar attempt at a new automobile: Kaiser-Frazer. K-F was launched by a sales executive who loved automobiles, Joseph W. Frazer. Frazer needed cash, so he teamed up with Henry Kaiser, doyen of wartime shipbuilding, backed by the best banks and credit in the country. Tucker didn’t find, nor apparently did he seek, an angel of such stature. One wonders what might have happened had he met Henry Kaiser.

Kaiser-Frazer’s initial capitalization was $52 million—and it wasn’t enough. Chevrolet had set $100 million aside just to redesign its 1949 models. Henry Kaiser later admitted, “we should have raised $200 million.” Tucker raised $15 million.

From incorporation to first cars took Kaiser-Frazer eighteen months; It took Tucker two and a half years. From moving into its new plant to its earliest pilot models took K-F only six months; it took Tucker eighteen.

Kaiser-Frazer’s first full year of 1946, which didn’t see any cars until June, ended with 12,000 units built and was followed by 140,000 in 1947. Tucker’s first full year of 1947 saw no cars, and fifty were built in 1948.

K-F’s maximum employment reached nearly 20,000; Tucker predicted 35,000, hut never broke 2000.

Kaiser-Frazer satisfied the Securities and Exchange Commission by admitting in its first stock prospectus that its program was a pure gamble. Tucker floated one stock issue and promptly created a mess for itself through several false statements and unsubstantiated claims in its prospectus. Preston was caught making indirect payments to promoters, planning to assign work to his mother’s machine shop in Ypsilanti which didn’t have the capacity. And the SEC, rightly or wrongly, never let him live it down.

Business strategies

Like Tucker, Henry Kaiser promised features that didn’t appear—unit body construction, torsion bar suspension, front-wheel-drive. Unlike Tucker, Kaiser substituted a car he could deliver. If it wasn’t what he had originally intended, at least it was a vehicle on four wheels that people could drive and buy.

Kaiser mapped out a production line covering millions of square feet with the help of an ex-Chrysler production expert. He was building 200 cars a day almost from the start. Tucker sent fifty cars down a conveyor and called it a production line.

When Republic Steel’s wartime blast furnace in Cleveland was put up for bids by the War Assets Administration, Tucker’s bid was highest. Then without warning in August, 1948, the WAA awarded it to Kaiser-Frazer. War Assets claimed K-F had raised the money, which they had. Tucker claimed WAA never told him the price was going up. But Jess Larson, WAA’s administrator, told Tucker his bid was inadequate and asked Tucker to demonstrate the ability to run the blast furnace on May 28th, long before Kaiser’s bid arrived.

It is interesting to look at what later happened to the Republic Steel furnace. When Kaiser got it, Republic protested, saying Kaiser-Frazer had “pulled strings.” Affronted, Henry Kaiser called for a congressional investigation. Larson told Congress he would mediate between K-F and Republic.

The feud ended with the plant going to K-F as high bidder, but allowing Republic to operate it through mid-1949, paying K-F to do so—but less than it would have had to pay War Assets in rent. Republic came out ahead, and in 1949 signed a five-year contract with K-F to retain the furnace while supplying K-F and other customers with steel. Everyone was happy.

Timeline anomalies

If the Kaiser-Frazer comparisons don’t tell you something, consider the Tucker timeline. The plant was taken over in 1946, yet the stock application didn’t come until June, 1947. What was happening in the meantime?

Tucker began selling stock in September, 1947, but was still trying to decide on an engine the following spring. The first 500 Aircooled Motors engines didn’t get ordered until May. What was happening in the meantime?

The first Tucker cars were delivered in prototype form in March 1948, but by August when the plant closed it had built only fifty. (Happily, most all of them survive.) Yet Tucker claimed to have a production line that would build 1000 cars a day by mid-1948. What was happening in the meantime?

One can only conclude of Preston Tucker that brilliant though he may have been, he made impossible promises. This alienated some of his best people. When patent attorney and Tucker board chairman, Col. Harry A. Toulmin, Jr., quit the company in September 1947, he pointed to “fast sell” practices such as promoting stock on the basis of an unfinished, untested single prototype.

The Tucker trial

It was cold in Chicago, that windswept January Sunday in 1950, and the atmosphere was reflected in the U.S. Courthouse on Atlanta Street—the same courthouse where the feds had finally convicted Al Capone.

Sadly, Preston Tucker was nearly without friends by the time of the trial. There were seven other defendants in court, and not one of them spoke very highly of him. Somewhere along the way he had alienated nearly everyone, which is quite an accomplishment. Former Sales VP Fred Rockelman, who had lengthy industry experience at Chrysler, was long estranged.

Another vice president, Herbert Morley, testified that $800,000 in Tucker receipts couldn’t be accounted for in 1947. In 1948 Morley had complained that Tucker’s mother was unable to build transmissions at her Ypsilanti Machine and Tool Company.

Even chief designer Alex Tremulis, who warmly supported Tucker’s engineering abilities, admitted that Preston wanted many impractical design ideas, such as front fenders that turned with the wheels and a periscope rearview device.

Now the jury was out—had been for some time. One may easily wonder what was going on behind Preston Tucker’s placid countenance, waiting for a verdict that could bring him a cumulative 155 years in jail and fines totaling $160,000.

But we never found out. Nor did we learn if Tucker could build another car. As the jury eventually told, he was cleared of 31 counts of conspiracy, mail fraud and illegal stock procedures. And by 1956 he was dead of cancer. Or, some said, a broken heart.

Conspiracy theories

The old song about General Motors “doing in the little guy” has oft been repeated over Tucker. Preston’s well-publicized defenses referred to a dark, clandestine attempt to thwart him. It’s rather odd, then, that Tucker electronics were supplied by GM Delco.

In Tucker’s defense, his case was an example of big government (as big as it was then) run paranoid. But that was a haphazard time after a major war. The Securities and Exchange Commission was not concerned only with Tucker in those days. In fact, its hands were fuller than they’d ever been.

Government watchdogs looked for promoters with an idea and enough money to push it, selling stock in a company designed to produce in the end nothing. Bureaucrats are dogged folk with great staying power, especially when somebody they’ve already scored a few points against takes to charging that they’re out to get him. Ask Donald Trump.

What about Senator Homer Ferguson, Republican from Michigan, and his Michigan appointee to the SEC, Harry A. McDonald, who leaked news of the SEC investigation to the press? Beyond doubt they acted unethically, especially McDonald. It would be the height of naïveté to believe the interests of their state’s main industry didn’t occur to them when they heard about Tucker. Yet even as McDonald ran his little plot to publicize the Tucker investigation, the company had a history of SEC violations dating to its first stock issue.

In retrospect

Preston Tucker, wrote auto historian Michael Lamm in 1973, “was essentially a smalltime promoter who’d gone big-time. He was out of his pond. He remained a stranger and perhaps even a threat to the SEC, and he didn’t know anyone in government. Preston was careless in some of his pencil-work, perhaps in a bit of his talk, too, and when the SEC jumped on him about those initial fifteen irregularities, the irregularities did exist.”

Well said. Nevertheless. Preston Tucker conceived one amazing automobile. Nevertheless, the government did overreact, despite all he did to earn it. If GM didn’t try to stop him, certain representatives of the state of Michigan did. With a different approach, three times more capital, and wiser business heads, the story might have been different. But hindsight is cheap, and far too easily indulged.

Notes and further reading

This piece is reprised from “Tucker: Brief Reflections,” The Milestone Car no. 11, Spring 1975; and “Postwar Cars: The Tucker Bubble,” Car Collector, January 1989.

See also “The Greatness of Alex Tremulis,” in three parts, beginning here.

And: “Kaiser-Frazer and the Making of Automotive History,” in two parts, beginning here.

One thought on “The Tucker Story (No, It Wasn’t the Car to Beat Detroit)”

Thanks for the cold dose of reality on an urban myth that refuses to die. I’ve often repeated to unwilling listeners that the Tucker film is just an urban myth with little to do with reality. It’s akin to the hoary old falderal that GM, Firestone, etc. bought and doomed the Los Angeles Red Line urban train system. That bit of tripe was still being taught in college in the mid-Eighties. I, a rather well versed thirty-something student at the time, argued with the professor, and (perhaps convincingly to a few in the class), deconstructing the myth in a presentation. I wonder if it’s still being taught.

Comments are closed.