“Since Thomas Jefferson Dined Alone”…. JFK, Winston Churchill

Q: Did Churchill praise Jefferson?

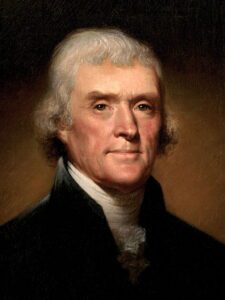

I listened with appreciation to your recommended podcasts of “Uncancelled History” by Douglas Murray. Particularly fascinating was his conversation on Thomas Jefferson with the historian Jean Yarbrough. Did Churchill have anything to say about this extraordinary, complex and learned Founding Father? —R.F., Connecticut

A: Yes, but first a digression…

Your question reminds me of a dinner for Nobel Prize Winners at the White House, 29 April 1962. President John F. Kennedy declared them welcome:

I think this is the most extraordinary collection of talent, of human knowledge, that has ever been gathered together at the White House, with the possible exception of when Thomas Jefferson dined alone.

Someone once said that Thomas Jefferson was a gentleman of 32 who could calculate an eclipse, survey an estate, tie an artery, plan an edifice, try a cause, break a horse, and dance the minuet. Whatever he may have lacked, if he could have had his former colleague Mr. Franklin here, we all would have been impressed.

Not even Churchill, I believe, paid a greater compliment to Jefferson than President Kennedy. Likewise, Uncancelled History is a font of Truth emerging from the Bodyguard of Lies that surrounds her in the present age.

Andrew Roberts on Churchill vies with Allen Guelzo on Washington as my favorite Uncancelled History episodes. And Jean Yarbrough’s Jefferson emerges from the blue distance of time as the truly sterling character her was. (Incidentally, the Sally Hemmings story is exploded as the slanderous myth it is. Watch it and decide for yourself.)

Hamilton and Jefferson

Churchill contrasts Jefferson and Alexander Hamilton in The Age of Revolution, Volume 3 of his History of the English-Speaking Peoples. We all learned about them in school—well, at least those of us “of a certain age.” What Churchill offers is the view of a fellow statesman, 150 years removed. And Churchill lived a life and experiences few—but certainly Jefferson—could claim.

Hamilton, writes Churchill, “symbolises one aspect of American development, the successful, self-reliant business world. He distrusted “the collective common man…’the majesty of the multitude.'” But Hamilton exhibited little of “the idealism which characterises and uplifts the American people.” Jefferson was “the product of wholly different conditions and the prophet of a rival political idea.” Churchill continues:

The outbreak of war between England and France was to bring to a head the fundamental rivalry and conflict between Hamilton and Jefferson and to signalise the birth of the great American parties, Federalist and Republican. Both were to split and founder and change their names, but from them the Republican and Democratic parties of today can trace their lineage.

Churchill on Jefferson:

He came from the Virginian frontier, the home of dour individualism and faith in common humanity, the nucleus of resistance to the centralising hierarchy of British rule. Jefferson had been the principal author of the Declaration of Independence and leader of the agrarian democrats in the American Revolution.

He was well read; he nourished many scientific interests, and he was a gifted amateur architect. His graceful classical house, Monticello, was built according to his own designs. He was in touch with fashionable Left-Wing circles of political philosophy in England and Europe, and, like the French school of economists who went by the name of Physiocrats, he believed in a yeoman-farmer society.

He feared an industrial proletariat as much as he disliked the principle of aristocracy. Industrial and capitalist development appalled him. He despised and distrusted the whole machinery of banks, tariffs, credit manipulation, and all the agencies of capitalism which the New Yorker Hamilton was skillfully introducing into the United States.

He perceived the dangers to individual liberty that might spring from the centralising powers of a Federal Government…. It was not given to him to foresee that the United States would eventually become the greatest industrial democracy in the world.

Churchill deeply respected Jefferson’s deeds and thought. His further remarks are in The Age of Revolution, Book 9, Chapter 17.

On education: Jefferson’s warning

President Kennedy’s awe of Jefferson, and Churchill’s generous appreciation, led us to a matter of current moment: education. In revising the laws of Virginia in 1778, Jefferson offered “A Bill for the More General Diffusion of Knowledge.” Its preamble speaks volumes on the need for a better educated electorate.

Jefferson believed the American Constitution protected the individual’s natural rights. Nevertheless, he observed, those “entrusted with power have, in time, and by slow operations, perverted it into tyranny.” That, he continues, must be prevented. The best preventive is education. Possessed of “the experience of other ages and countries,” educated citizens will recognize “ambition under all its shapes.” They will exert “their natural powers to defeat its purposes.”

A people will be happiest “whose laws are best, and are best administered…. If those who “form and administer” those laws are “wise and honest.” Education produces people “worthy to receive, and able to guard the sacred deposit of the rights and liberties of their fellow citizens…without regard to wealth, birth or other accidental condition or circumstance.” It is therefore more important that children “should be sought for and educated at the common expense of all, than that the happiness of all should be confided to the weak or wicked.”

Jefferson today

Former Speaker of the House Newt Gingrich looks at Jefferson in a very thoughtful podcast. He shows, I think, how Jefferson’s thoughts remain evergreen—and ever more important today:

Now, if you go back and re-read that, you realize our current situation: Schools that don’t teach. Teachers that don’t educate. Avoidance of history. Dumbing down of mathematics. Giving people passing grades so they feel good even if they know nothing. You can sense that we have arrived at a counter-Jeffersonian moment, when everything Jefferson feared, in terms of ignorant people giving up their freedoms, is far too close to becoming a reality. That’s why Jefferson is always worth revisiting, and thinking about.

The Virginia House of Delegates rejected Jefferson’s Bill in 1778 and 1780. His friend James Madison presented it repeatedly while Jefferson was serving in Paris as Minister to France. In 1796 a revised version finally passed as “Act to Establish Public Schools.”

Further reading

“Reflections on the Birthday of George Washington,” 2023

2 thoughts on ““Since Thomas Jefferson Dined Alone”…. JFK, Winston Churchill”

IS THIS MYTH OR TRUTH :

JEFFERSON COULD WRITE ENGLISH WITH ONE HAND AND FRENCH WITH THE OTHER – SIMULTANEOUSLY??

Langvorts, Bravo! You have managed to cover three of my heroes in a single essay–Churchill, Jefferson and JFK. They are constant companions in my reading and my thinking. All the best from your old friend, Russells

Comments are closed.