The Sordid History of Churchill’s Collected Works

Excerpted from “The Sordid History of the Collected Works,” my essay for the Hillsdale College Churchill Project. To read the original article with more photos and an appendix on the various texts, click here. To subscribe to weekly articles from Hillsdale, click here, scroll to bottom, and fill in your email in the box entitled “Stay in touch with us.” Your email address is never given out and remains a riddle wrapped in a mystery inside an enigma.

Fanfare

In 1973, on the eve of the Churchill Centenary, word broke of the first collected edition of Sir Winston’s published works. Edited by Frederick Woods, The Collected Works of Sir Winston Churchill was “limited to 3000 copies.” The price was £945, then about $2500. The publisher was the “Library of Imperial History,” a company apparently founded to market the books.

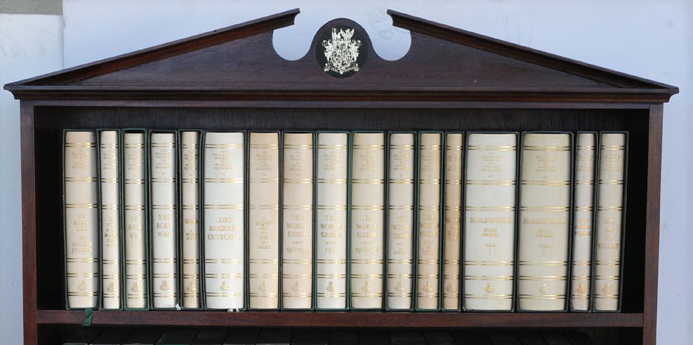

Aesthetically, the set seemed magnificent, bound in calfskin vellum with the titling in 22 ct. gold, printed on “500-year archival paper,” page edges gilt, silk page markers, marbled endpapers. (They proved to be color separations, not marbled paper, a minor disappointment.) Each volume was housed in a dark green slipcase stamped with the Churchill Arms.

The specifications were titanic: five million words, 19,000 pages, 90 pounds, requiring 4 1/2 feet of shelf space. The Collected Works were promoted with impressive testimonials. Lady Churchill, who wrote the Foreword to Volume I, said the books would have given Sir Winston “enormous pleasure.”

Brickbats

Public opinion was less uniform. Dalton Newfield, editor of the International Churchill Society journal Finest Hour, editorialized: “Triumph? No—Tragedy.” Most people, he wrote, “will never own this wonderful work…. Few libraries will find $2500 for an edition so expensive. Clearly the Works are canted toward the speculator.”

He also questioned the claim that “a substantial part of the proceeds…will be used to further the work of the Churchill Centenary Trust, Churchill College and the U.S. Churchill Foundation.” His doubts proved valid, for there is no record that those charities ever benefitted. The price also rankled. By contrast, Newfield noted, the Encyclopedia Britannica had three editions from $998 to $5000. But “all who want to use this valuable reference will be able to buy it for just under $500, and EB will knock another $100 off if you trade in any old edition. What a contrast!”

Scholarship

Newfield also raised problems of scholarship. Most of the works were being reset and reedited. Some texts were taken from later editions, which differed radically from the originals. The worst offender was The River War, which appears in the Works only as an abridgment, a far cry from the original text. The World Crisis, with its valuable shoulder notes, looks at a glance like an offprint of the First Edition. In fact it was reset, reedited and its maps redrawn.

In all, only eight volumes and half of a ninth contained the original text and pagination. Seven volumes were offprinted from later editions. The other 18 1/2 volumes, though improved with uniform type and better maps, bear no resemblance to the originals. They are of limited value for footnotes or references, since the Collected Works are so rare that few can access them.

The reset works were also significantly edited. While in this may have improved or modernized the text, it created enormous differences from the original. If editor Woods could change “Currachee” to “Karachi,” was he not also tempted to change whole passages? “I concede that WSC’s works can stand a lot of editing, particularly his maps and quotations,” wrote Newfield. “But such editing, of course, makes the issue useless for student and scholar.”

Omissions

The title Collected Works was itself misleading, since only Churchill’s books and some of his speeches were included. Forewords and contributions to other books, contributions to press and periodicals, and most speeches were omitted. The Library of Imperial History reacted to this criticism when it issued, in 1976, the Collected Essays of Winston Churchill, a four-volume compilation of most major articles, forewords and contributions not in the Works. Purchasers of the Works were allowed to add the four-volumes of Essays, and a less expensive binding of the Essays was offered. The Essays, still not reprinted a half century later, are a true contribution to the Churchill canon. They will be described in a separate article.

Disappointments

Shortly after publication the price rose to £1060 in Britain and $3000 in America. This did nothing to encourage sales. By early 1976, all signs pointed to somewhat less than the sell-out the publishers had promised. In a much plainer prospectus issued that year, it was admitted that only 1750 of the authorized 3000 sets were sold. Sets were being bound only as orders were received.

By the late 1970s the company declared bankruptcy. The receivers relocated their offices from London to Royal Tunbridge Wells, and fitful efforts were made to dispose of further sets, without much success.

By 1982, when I attempted to locate the Tunbridge people, both they and the stock of the Works and Essays had vanished. It was rumored that the stock had been bought and moved to New York. But when a New York bookseller colleague went personally to the location, he found an “accommodation address.”

Search

For years, as a Churchill bookseller, I tried to rediscover the thread of the “great venture.” Finally I found a firm of London solicitors who had been involved in the liquidation. They had no clue as to the whereabouts of stock, but referred me to the bindery, Robert Hartnoll Ltd. in Bodmin, Cornwall.

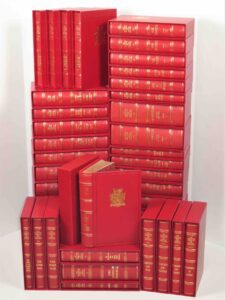

Success! For the past few years Hartnolls had been warehousing enough leftover sheets to make up several hundred sets. The unknown New York entrepreneur had apparently bought the sheets and persuaded the bindery to make up 20 sets of Collected Works in red morocco. The bindings differed in detail with the original, and lacked the original publisher’s spine logo. But there were enough unbound sheets left to satisfy my clients who wanted them.

Alas, the process of making the Works available was a test of will, time and patience. UK law moves slowly, and Hartnolls were told that seven years must pass before they could consider the books theirs to sell. Otherwise, the owner might resurface and accuse them of dealing in stolen property!

I kept at them: “Isn’t there some way you can meet the law and still sell the stock?” In 1987, three years after I had located the trove, they thought of one: Sell books, but keep the proceeds in an escrow account for the prescribed number of years. In this way Hartnolls would meet the letter of the law while the Churchill world would get the books many wished to own.

Recovery

A renowned bindery specializing in Bibles, Hartnolls was founded in 1960 and closed in 2019. Its work was spectacular, and it happily bound books to order. Many collectors opted for morocco-bound Works, instead of vellum, which tends to discolor and swell with age. To this day my own set, bound in cream morocco, “falls open like angel’s wings” (as Churchill said of his History of the English-Speaking Peoples), and smells like the inside of a Bentley. These and other later morocco bindings, with cloth endpapers and gilt dentelles on the inside cover edges, are even more elaborate than the originals. They are wonders of the binder’s art.

Over the years my friend and bookseller colleague Mark Weber and I sold the remaining available sets. We sold about 20 sets bound in full cream morocco, using the original dark green slipcases. Several more sets were bound in vellum or red morocco. (The latter carried the original spine markings, LIH logo, and red bookcloth endpapers.) Counting early and later bindings, about 50 sets exist in red morocco.

One-offs

Original advertisements showed the Collected Works in a bespoke bookcase topped by a pediment bearing the Churchill Arms. Surprisingly, the bookcase was never offered to the public and apparently only one was built for advertising purposes. Mark Weber discovered it years later—originally owned by Sir Iain Maxwell Stewart, a Scottish shipbuilder. Sir Iain, who served on many boards, was a director of the Churchill Centenary Trust, which presented him with this uniquely housed example. An important clue to final quantity produced is the attached brass plaque, which mentions an edition of 2000, not 3000 as originally advertised.

As sheets were running out, Mark Weber commissioned one grand finale set of Collected Works. Just before his untimely death in 2016, Mark bound this last set in dark green pebble-grained goatskin. It features leather inner hinges, silk endpaper inserts and premium cloth slipcases with leather tops and bottoms. As a final touch, Volume I bears the signatures of Hartnolls craftsmen, some of whom had worked on these sets since the mid-1970s.

Appraisal

The Collected Works are less important than their spectacular appearance suggests. However incomplete, they do constitute the first collected edition. But lacking the original texts, they are not bibliographically compelling: “expensive reprints,” as one cynic put it. Collectors prefer to hold a book in the form Sir Winston first gave it to the world—errors and all. The Collected Works will never replace first editions.

Dalton Newfield was certainly right to think the Collected Works were “canted toward the speculator.” In the late 1980s sets sold for about $2000 (38 volumes including the four Collected Essays). That is roughly $5000 in today’s money, but clean sets today sell now for $8000 or more, and mint sets for double that, when you can find them. The later morocco bindings are higher—$20,000 currently for a red “New York” set. The highest price we know of (a bespoke binding) is $27,500. Still, a $3000 annuity taken out in 1974 would probably produce better returns.

Acknowledgements

The author wishes to thank Barry Singer of Chartwell Booksellers and Marc Kuritz, of the Churchill Book Collector, for kind assistance in researching values and binding variations, and for permission to reprint some of the above images.