Guelzo on Robert E. Lee: “To Err on the Side of Absorbing Society’s Defaulters”

Allen C. Guelzo, Robert E. Lee: A Life (New York: Knopf, 2021), 608 pages, illus., $35, Kindle $15.99. First published in The American Spectator, 9 November 2021.

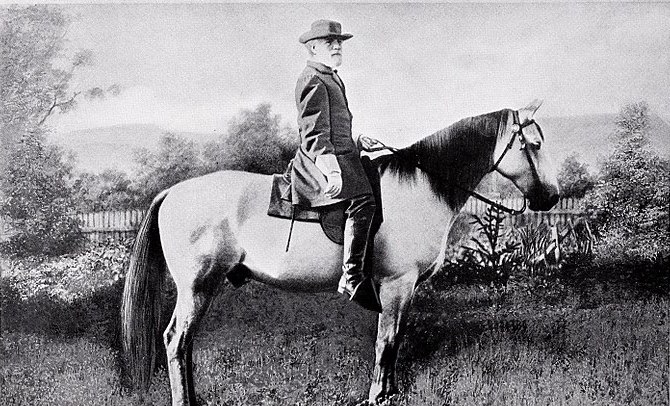

“Who’s that man on the horse?”…

…I asked my father at a young age. “That’s Lee—he led a Southern army in the Civil War.” He gave me a book I still have, Illustrated Minute Biographies, by William DeWitt. Published 1953, it is utterly non-judgmental. Opposite the page on Lee (“Leader of a Lost Cause”) is a page on Lenin (“Father of the Russian Revolution.”)

…I asked my father at a young age. “That’s Lee—he led a Southern army in the Civil War.” He gave me a book I still have, Illustrated Minute Biographies, by William DeWitt. Published 1953, it is utterly non-judgmental. Opposite the page on Lee (“Leader of a Lost Cause”) is a page on Lenin (“Father of the Russian Revolution.”)

Among DeWitt’s 150 personalities, Lee fascinated. I’ve always had a soft spot for underdogs. The moral injustice which the Civil War ended didn’t initially register. Nor did the enormity of Lee’s decision over which side to support. Civil War themes were popular. We kids wore replica Yankee and rebel soldier’s caps, not really knowing much about why they fought.

But the New York City public school system taught serious history in those days, and soon corrected our ignorance. Our teachers introduced us to the great wrongs of slavery and secession. They showed us the genius of Lincoln; the skill of Grant; the valiant, brilliant resistance of Lee.

As a child of that time I was saddened over the recent rush to pull down memorials to him—“less about understanding the past than a contest to divide us,” as Dan McLaughlin wrote. A better response is to erect more statues, as Hillsdale College did for Frederick Douglass—replying to history with more history.

Allen Guelzo’s new Lee biography is unmatched as an example of history taught with balance and understanding, as it was when I went to school. George Will thinks its timing couldn’t be better: “In today’s blizzard of facile, overheated, and grandstanding judgments about the past, this unsentimental biography illustrates the intellectual responsibility that the present owes to the past.”

Woke villain

Of course the first question one asks is: Why Lee? Especially now, when he’s a leading villain of the Woke Movement? Dr. Guelzo explained in an illuminating podcast with former Speaker Newt Gingrich. He actually began in 2014, before the advent of national distemper. Fired up, he had just published a best-seller on Gettysburg.

He focused on Lee because, compared to giants like Lincoln, Grant and Sherman, he was relatively underwritten. True, there were early hagiographies, and a Pulitzer-winning four volumes by Douglas Southall Freeman in the 1930s. But otherwise the field was relatively open.

Admittedly, it’s a challenge to write about someone many consider a traitor. Guelzo, a “northern Yankee,” defines the job as “difficult biography, like writing about Neville Chamberlain.” That is part of the fascination of his book—amplified by his skill in exposing Lee’s true character, the great impulses that drove him, and the decisions which placed him athwart the nation he loved and had sworn to protect and defend.

Truant Virginian

It takes 200 pages to get to that point, and the build-up is anything but dull. Lee last saw his father at the age of six. Washington’s famous cavalry general, Light-Horse Harry Lee, onetime Virginia governor, went through several fortunes and ruined himself, spending his last years in the West Indies. That left Robert with two powerful compulsions: perfection, to make up for his father’s shortcomings; and security, which his father’s profligacy had denied him.

Only in his last five years, as the unlikely president of a small college in Lexington, did Lee achieve those goals; remarkably, he was as effective a fundraiser as a military strategist. He raised what became Washington and Lee University from bankruptcy to prominence.

Lee commanded no troops in the field until he served under Winfield Scott in the Mexican War (1846-48). He was educated at West Point, America’s premier engineering school before the Civil War. He returned later as superintendent (1852-55), hating every minute of it, for he despised paperwork and interfering politicians.

The work he most enjoyed was building things: Savannah’s Fort Pulaski and improvements at other Army installations. In 1839 he changed the course of the Mississippi River and rebuilt the St. Louis waterfront.

Ironically, between West Point and Brooklyn’s Fort Hamilton, Lee spent more early adult years in New York than in Virginia. Arlington House in Alexandria County, the Lee home for 30 years, was part of the District of Columbia until 1846, and Lee never even owned it. Yet it was Virginia which commanded his loyalty in 1861.

The hinge of fate

Lee’s fateful decisions were threefold. In February 1861, seven states seceded to form the Confederacy. On 18 April Lee turned down Lincoln’s offer to command the Union Army. “If I owned the four millions of slaves in the South,” Lee exclaimed, “I would sacrifice them all to the Union: but how can I draw my sword upon Virginia, my native State?”

Scott and Lincoln assured him there was no chance of this, but the next day Virginia seceded and joined the Confederacy. Tearfully Scott begged: “For God’s sake, don’t resign.” “I am compelled to,” Lee cried. “I can’t consult my feelings in this matter.”

“There is no glimpse of Lee thinking his way through the contradiction slavery posed to the American founding or the natural rights of the enslaved,” Guelzo writes. Though he freed Arlington’s slaves, to Lee they were “personally invisible, despite their presence all around.” Late in the war, he favored offering freedom to slaves who would fight with his army, and some did. The reaction of the army was “at best ambivalent.”

Lee’s thinking began with family: All his children possessed lay in Virginia. “They will be ruined if they do not go with their State. I cannot raise my hand against my children.” If he had, the state militia might have seized Arlington (in the event, the Union did). But remaining neutral would have made him a traitor in the eyes of both sides. So Lee could only hope that Virginia would not secede. “Save in her defense there will be one soldier less in the world than now.”

Save in her defense…. A day later found Lee in Richmond, where he hoped to mediate a peaceful settlement. There was none, and on 22 April he placed himself “at the service of my native state.”

Strategist and tactician

The accounts of Lee’s campaigns are brisk and revelatory without dunning us with detail. (Unfortunately, detail is sometimes lacking in the accompanying maps.) Twice taking the war to Union territory was the right strategy, Guelzo says.

We see the agate points at which, had things gone otherwise, Lee might have forced an armistice. Guelzo discounts the rumor that Lee and McClellan, neither defeated after Antietam, considered marching jointly on Washington, confronting Lincoln and compelling a settlement.

McClellan didn’t have that much imagination. He failed to press Lee at Antietam, as Lee had anticipated. “Some day,” Lee cracked, “they’re going to have a general I don’t understand.” (Some day they did.)

Lee was overly romanticized after the war, but contrary to recent criticisms, we see an audacious strategist whose attacks when he was expected to retreat won battle after battle. Tactics he usually left to subordinates, who were not always of the first caliber. When they were, the results were astonishing.

Norman Schwarzkopf, says the author, overwhelmed Saddam Hussein’s Republican Guard in the 1991 Gulf War with the same sweeping flanking movement of Chancellorsville, where Lee allowed Stonewall Jackson to attack with his whole corps, risking everything—and ultimately losing Jackson himself.

Even at Gettysburg, Guelzo suggests, Lee’s strategy on day three was not all wrong. Union General Meade, broadly beaten the first two days, was actually preparing to retreat when George Pickett charged Cemetery Ridge. The rebels failed through the valor of Union troops who, though badly mauled earlier were determined not to yield. Pickett was asked later why he failed. “The Yankees fought,” he drawled.

Was Lee a traitor?

At Hampton Roads in January 1865, Lincoln met with Confederate plenipotentiaries inquiring about an armistice. There would be none, he declared, short of reestablishing “our one common country” and abolishing slavery. One asked whether that meant “we of the South have committed treason.” Lincoln replied, “You have stated the proposition better than I did.”

Dr. Guelzo is thoughtful on this question as applied to Lee. He meets the constitutional definition: “levying war against [the United States] or in adhering to their enemies, giving them aid and comfort.” At the same time the author cites serious constitutional obstacles to convicting Lee (he was indicted, but never tried).

First, Grant had paroled Lee and his top officers at Appomattox, and a paroled prisoner-of-war cannot be classified legally as a traitor. Even Lincoln insisted that the Confederacy had no standing as a nation. It was an enemy, but not a foreign enemy. America’s greatest convulsion was a family affair—a war not only between states, but between households, kinsmen, brethren.

Conscious of his parole, Lee gave no encouragement to his indictors. He discouraged Jubal Early from a guerrilla movement which would “prolong bitter feeling and postpone the period when reason and charity may resume their sway.” He opposed a monument to Confederate war dead, which “would have the effect of retarding, instead of accelerating,” peaceful recovery.

Well, Dr. Guelzo says, he didn’t say that monument might not be deserved; and he took “no positive steps to cooperate with Reconstruction.” Given Lee’s devotion to his troops, for him to say no monument was deserved was inconceivable. And his last five years at Washington College were reconstructive. He never spoke at die-hard rallies, or gave encouragement to bitter-enders. But perhaps doing nothing is not enough.

“Absorbing society’s defaulters”

The nation-state with all its faults, Guelzo concludes, provides “a frail but workable insurance against the kinds of incessant dynastic, ethnic and religious warfare that used to be the common lot of the human race…. To wave away treason as a crime is to put in jeopardy many of the benefits the nation-state has conferred.”

That is a valid observation, but the author continues: “…perhaps the reluctance to pin [treason on Lee] is a token of an instinct, running back to the Constitutional Convention, to err on the side of absorbing society’s defaulters, rather than arching them to the scaffold.” He quotes the abolitionist Wendell Phillips: “We cannot cover the continent with gibbets. We cannot sicken the 19th century with such a sight.”

No, or the 21st century likewise.

Most of Lee’s class owned slaves, yet he told Confederate President Jefferson Davis that slavery was a curse that must go. But he didn’t think about when and how—nor did quite a few people, North and South. A century hence, if there are still historians, will they marvel over some of our slipshod thinking today?

Modern scolds may be outraged that Allen Guelzo has written this majestic biography. He will be called names for his trouble. But Dr. Guelzo quotes the literary critic John Gardner: “No true compassion without will, no true will without compassion.” The two have to meet, he says.

“Malice toward none; charity for all.” In their interview, Speaker Gingrich observes that Lincoln has affected him. “Yes,” says our author, “I believe so.”

Further reading

“Churchill’s Fantasy: If Lee Had Not Won the Battle of Gettysburg”

“Robert E. Lee and the Fashionable Urge to Hide from History“