Churchill’s Fantasy: “If Lee Had Not Won the Battle of Gettysburg”

Excerpted from the Hillsdale College Churchill Project. Why settle for the excerpt when you can read the whole thing ? Click here.

Please join 60,000 readers of Hillsdale essays by the world’s best Churchill historians by subscribing: visit https://winstonchurchill.

“Sir Winston’s Gettysburg essay…

...is a fantasy which transcends all my objections to exploring the what-ifs and might-have-beens in that great war.” —Shelby Foote

“If Lee Had Not Won the Battle of Gettysburg” first appeared in Scribner’s Magazine, December 1930 (Cohen C344). It resurfaced a year later in a collection of alternate histories, If It had Happened Otherwise (Cohen B43). Its last appearance, in 1975, was in The Collected Essays of Sir Winston Churchill, (Cohen 286). A copy is available by email for personal use but not for reproduction. —RML

Paul Alkon on Churchill at Gettysburg

Dr. Paul A. Alkon was Bing Professor Emeritus of English and American Literature at the University of Southern California. His appreciation of Churchill’s Gettysburg alternative history is the best I’ve read. It is excerpted below from Paul’s book, Winston Churchill’s Imagination, by kind permission of Ellen Alkon. To this I added brief excerpts (italics) from Churchill’s actual 1930 essay.

1930: Gettysburg imagined

“Once a great victory is won it dominates not only the future but the past…. Still it may amuse an idle hour [if] we meditate for a spell upon the debt we owe to those Confederate soldiers who by a deathless feat of arms broke the Union front at Gettysburg and laid open a fair future to the world.”1

Experience in battle on four continents gave Churchill a horror of war. He also gained an ability to imagine alternate scenarios. It is shocking to realize that the worst possible outcome after the First World War came to be, just two decades later. Contemplating the causes of that war, Churchill with his historic imagination conjured up a scenario which might have prevented it—in 1863.

“If Lee Had Not Won the Battle of Gettysburg,” is Churchill’s only freestanding speculation about a different historical outcome. It is a classic of the genre “alternative history” in science fiction. Some historians refer to it—often suspiciously—as “counterfactual history.”

Churchill presents his story as written in a world where Lee did win the Battle of Gettysburg. As a consequence the South won the American Civil War. Implausibly from our viewpoint, we are told that Lee’s victory precipitated a sequence of events leading to the abolition of slavery, closer links among the English-Speaking Peoples, avoidance of the First World War, and the prospect of a United States of Europe led by Kaiser Wilhelm II.

1863: Lee the Emancipator

“If Lee after his triumphal entry into Washington had merely been the soldier, his achievements would have ended on the battlefield. It was his august declaration that the victorious Confederacy would pursue no policy towards the African negroes which was not in harmony with the moral conceptions of Western Europe, that opened the high roads along which we are now marching so prosperously.”*

As the story unfolds, Lee’s army marches victoriously to Washington, Lincoln’s government having fled to New York. Here Churchill must explain how Lee acquired plenary authority. Churchill deftly explains that Gettysburg threw Confederate President Jefferson Davis “irresistibly, indeed almost unconsciously, into the shade.” There is a grain of reality here, for Lee had warned Davis that slavery was the unacceptable wrong that would doom their cause. The North began the war fighting against Secession, Churchill explains. But “the moral issue of slavery had first sustained and then dominated the political quarrel.”

1905: The “English-Speaking Association”

Given the North’s preponderance of wealth and industry, losing at Gettysburg would not have daunted Abraham Lincoln. But in Churchill’s vision, “Lee’s declaration abolishing slavery…undermined the obduracy of the Northern States:

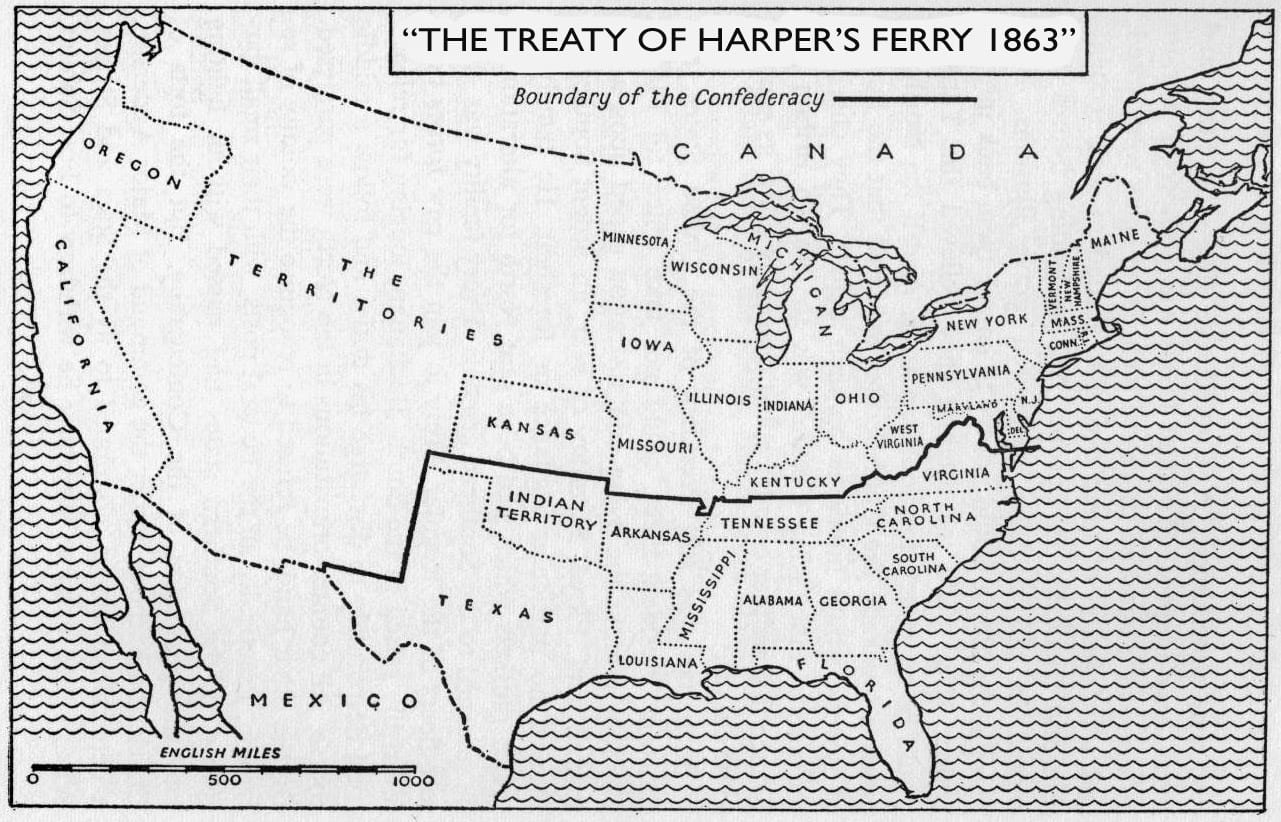

“Lincoln no longer rejected the Southern appeal for independence. ‘If,’ he declared…‘our brothers in the South are willing faithfully to cleanse this continent of negro slavery, and if they will dwell beside us in goodwill as an independent but friendly nation, it would not be right to prolong the slaughter on the question of sovereignty alone’…. The Treaty of Harper’s Ferry, which was signed between the Union and Confederate States on 6 September 1863, embodied the two, fundamental propositions: that the South was independent, and the slaves were free.”*

The United and Confederate States of America, riven after Gettysburg, thus become permanent republics. They live peaceably side by side—both armed to the teeth—through 1905. When war scares erupt in Europe, they join with Great Britain to form the “English-Speaking Association.” The signatories are President Theodore Roosevelt, Prime Minister Arthur Balfour, and Woodrow Wilson, “the enlightened Virginian chief of the Southern Republic.” Not a decade later, the “E.S.A.” forestalls world catastrophe.

1914: “Saved! Saved! Saved!”

Everyone remembers the perilous days of 1914, Churchill writes. The murder of the Austrian Archduke precipitated general mobilization. It was “the most dangerous conjunction which Europe has ever known. It seemed that nothing could avert a war which might well have become Armageddon itself.” Desultory firing had already broken out when the English-Speaking Association

“…tendered its friendly offices to all the mobilized Powers, counselling them to halt their armies within ten miles of their own frontiers, and to seek a solution of their differences by peaceful discussion. The memorable document added ‘that failing a peaceful outcome the Association must deem itself ipso facto at war with any Power in either combination whose troops invaded the territory of its neighbour.’ Although this suave yet menacing communication was received with indignation in many quarters, it in fact secured for Europe the breathing space which was so desperately required.”*

The French Republic, the Emperor Franz Joseph and Czar Nicholas quickly acceded to the E.S.A.’s “friendly offices.” The German Kaiser was the last to agree. Some say Wilhelm was determined on war regardless. Others insist he uttered “a scream of joy and fell exhausted into a chair, exclaiming, ‘Saved! Saved! Saved!’”

Our world as dystopian and improbable

Churchill’s imaginary resident of this imaginary world speculates in vintage prose about what dreadful events Lee’s victory prevented. Had the Union triumphed, armies of carpetbaggers might have descended to exploit the newly freed slaves. The South, simmering in resentment, might have invoked racial oppression. Benjamin Disraeli, that Liberal reformer, might have become a Tory! “The sabres of Jeb Stuart’s cavalry and the bayonets of Pickett’s division” turned William Gladstone from a Liberal to a “revivified Conservative.” (In reality, of course, Disraeli was the Tory, Gladstone the Liberal.) Churchill waxes lyrical in his fantasy:

“Once the perils of 1914 had been successfully averted and the disarmament of Europe had been brought into harmony with that already effected by the E.S.A., the idea of a ‘United States of Europe’ was bound to occur continually. The glittering spectacle of the great English-Speaking combination, its assured safety, its boundless power, the rapidity with which wealth was created and widely distributed within its bounds, the sense of buoyancy and hope which seemed to pervade the entire populations; all this pointed to European eyes a moral which none but the dullest could ignore.”*

The reader sees from a surprisingly utopian perspective, our own world as both dystopian and implausible. So the narrator mentions Jan Bloch’s once-famous book, The Future of War, which predicted with what proved remarkably accurate military detail the devastation that would attend war between major European states. But Bloch insisted that such a war would never happen.2

But Churchill asks: Suppose it had? A prostrate Europe might have descended into depression, unemployment, Bolshevism and fascism. Why, today in Britain the income tax might even be 25%! (In actuality, as we sadly know, all those things happened.)

1932: Implausible reality

The brilliance of Churchill’s essay also lies in his decision to shift its narrative viewpoint. We readers must not only consider the consequences of a Confederate victory—including the absence of the First World War. We must also imagine how inconceivable our world might seem if things had worked out differently.

“Whether the Emperor Wilhelm II will be successful in carrying the project of European unity forward by another important stage at the forthcoming Pan-European Conference at Berlin in 1932 is still a matter of prophecy. Should he achieve his purpose he will have raised himself to a dazzling pinnacle of fame and honour…and no one will be more pleased than the members of the E.S.A. to witness the gradual formation of another great area of tranquility and cooperation like that in which we ourselves have learned to dwell….”*

Churchill’s political imagination also allows him to portray dramatically different outcomes of a situation. So he invokes the implausibility of what actually happened—the gigantic slaughter of the Civil War and First World War. This foreshadows the rhetoric which in 1940 rallied his country by inviting contemplation of a Nazi victory. Too many dismissed such a thought. But Churchill knew a Hitler triumph would plunge the world “into the abyss of a new Dark Age.”

That chilling thought acquires much of its power by inviting imagination of one possible future: An alternative, feudal period, and technological development more accelerated than anything during the medieval era.

“Broad, sunlit uplands”

In June 1940, Churchill invited Britons to think of the worst possible outcome of Britain’s fight against Hitler’s Germany—not as a unique situation, incomparable with anything that had gone before, but also an alternative past wrenched out of time. He then invokes the more desirable outcome: “If we can stand up to him, all Europe may be free and the life of the world may move forward into broad, sunlit uplands.”3 Churchill’s skill as an alternative historian notably enhanced the rhetoric that he so famously mobilized for war.

“If this prize should fall to his Imperial Majesty, he may perhaps reflect how easily his career might have been wrecked in 1914 by the outbreak of a war which might have cost him his throne, and have laid his country in the dust. If today he occupies in old age the most splendid situation in Europe, let him not forget that he might well have found himself eating the bitter bread of exile, a dethroned sovereign and a broken man loaded with unutterable reproach. And this, we repeat, might well have been his fate, if Lee had not won the Battle of Gettysburg.”*

Endnotes

1 Winston S. Churchill, “If Lee Had Not Won the Battle of Gettysburg,” in Michael Wolff, ed., The Collected Essays of Sir Winston Churchill, 4 vols. (London: Library of Imperial History, 1975), IV Churchill at Large, 73. All subsequent italicized excerpts (*) are from this edition, pages 73-84.

2 Ivan (Jan) Bloch, The Future of War in Its Technical, Economic and Political Relations: Is War Now Impossible?, trans. R.C. Long (Boston: Ginn, 1899). abridged edition, also 1899.

3 “Their Finest Hour,” House of Commons, 18 June 1940, in Winston S. Churchill, Blood, Sweat, and Tears (New York: Putnam, 1941), 314.