Churchill: Scattershot Snipe and the Answers to It

My brother Andrew Roberts, author of the new and vital Churchill: Walking with Destiny, passes along a reader snipe which nails rickety new planks on the creepy ship Churchill Snipes. Incredible as it may seem, the writer manages to create a few we’ve never heard before. They will be added to my “Assault on Churchill: A Reader’s Guide.” As will another farrago by a loopy astronaut, about which you’ve probably already heard.

Snipe synopsis

Snipe 1) “Why doesn’t Andrew Roberts spell out Churchill’s mistakes? They were not all that innocent.”

Whole seminars could be devoted to whether Churchill’s mistakes—in fact exhaustively catalogued by Roberts—were innocent and well intended, or maliciously calculated. In forty years I’ve read nothing to indicate the latter. The charge is ridiculous.

Snipe 2) “His war tactics were not very good despite advice from Americans. In World War I he together with Kitchener proposed attacking Turkey at Gallipoli, with a total lack of knowledge of Turkish power.

Wrong. Churchill’s first impulse was to get at Germany by naval action via the Baltic Sea. On 28 October 1914 Turkey entered the war on he side of the Germans. The Turks mined the Dardanelles, bottling up the Russians, who appealed for help. Churchill ordered a naval bombardment of outer Dardanelles forts “from a safe distance,” thinking “the days of forcing the Dardanelles were over.”

Easy victories in early skirmishes made him think again, especially when Mediterranean commander Admiral Carden said he thought the Navy could force the straits. The War Cabinet believed an allied fleet appearing off Constantinople might force Turkey to surrender. The Gallipoli landing occurred months after the Dardanelles operation stalled. On-scene commanders botched both actions. All of this is clearly presented in Chapter 12 of my book, Winston Churchill: Myth and Reality. See also “Dardanelles-Gallipoli Centenary” herein.

Those poor Iraqis

Snipe 3) “In 1920-22 he bombed Iraqi tribes with airplanes instead of giving them independence because he wanted the oil from Mosul for his fleet.”

It wasn’t his fleet, it was Britain’s. Its oil was secured by the Anglo-Persian oil deal. Churchill wasn’t even in charge of the Admiralty in 1920-22. As Colonial Secretary he not only gave Iraq independence, he yearned to wash his hands of it. Writing Prime Minister Lloyd George, he called Iraq an “ungrateful volcano” from which Britain got “nothing worth having.” (The thought sounds eerily familiar today.)

On aerial bombing, Martin Gilbert wrote in Winston S. Churchill, vol. IV, pages 796-97: “At the beginning of June Churchill learnt from the War Office that aerial action had been taken on the Lower Euphrates, not to suppress a riot, but to put pressure on certain villages to pay their taxes. He telegraphed at once in protest to [Middle East Administrator] Sir Percy Cox. “Aerial action is a legitimate means of quelling disturbances or enforcing maintenance of order,” he wrote, “but it should in no circumstances be employed in support of purely administrative measures such as collection of revenue.”

Cox replied that the bombing had not been to punish villages for not paying taxes but to suppress rebels testing whether Iraqi authorities could rely on Britain. Churchill “withdrew his rebuke, minuting on Cox’s telegram a short but emphatic reply: ‘Certainly I am a great believer in air power and will help it forward in every way.'”

A Snipe over Gertrude

Snipe 4) “Gertrude Bell committed suicide because of him.”

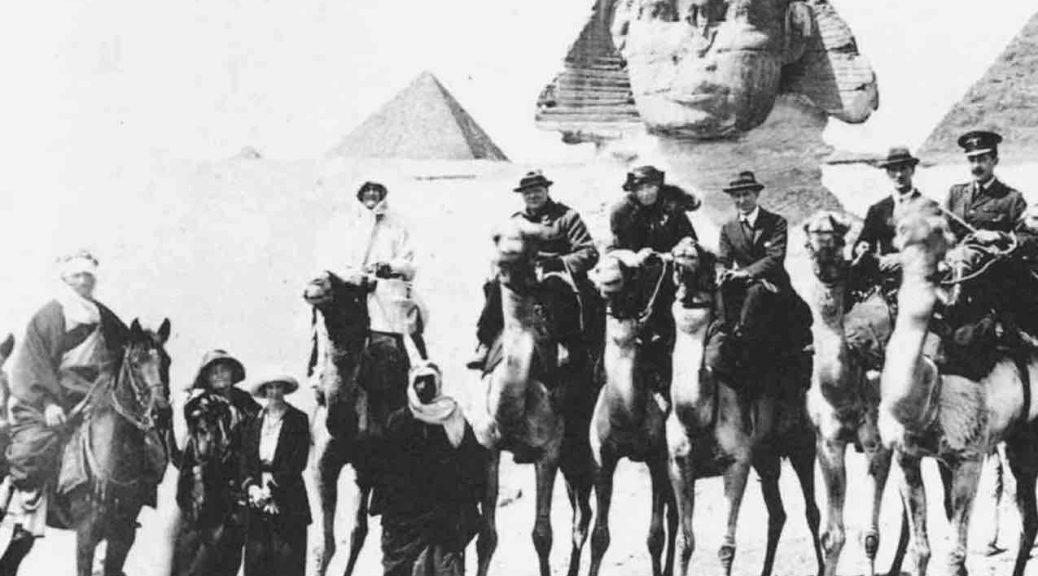

Why ever for? From Churchill, Gertrude Bell got everything she wanted in the Middle East: break-up of the Ottoman Empire; Arab States in Iraq and Jordan; Arab kings Feisal and Abdullah as respective kings. (Bell hoped they would become unifying figures; Abdullah’s descendant rules Jordan today.) Bell suffered from pleurisy. She died of an overdose of sleeping pills, whether intentional or not is unknown. (Incidentally, it was Bell and Lawrence who talked Churchill out of creating a separate Kurdistan. In retrospect, doing so would have spared the region less trouble.)

* * *

Snipe 5) “Probably his biggest error was to fix the US$/£ exchange rate at 4.1 in 1929, the damage caused much unemployment throughout the 1930s.”

Rubbish. The post-World War I recession and heavy debt sank the pound to $3.66 by 1920. Under Churchill as Chancellor (1924-29) and with the Gold Standard, it rose to $4.80, its prewar level. The pound’s devaluation to $4.10 occurred after Britain left gold on 12 September 1930, over a year since Churchill had left office. Depression and unemployment caused the pound to sink, not the other way round.

Snipe 6) “All that said, no one would have had the courage to continue to battle Hitler through all the years of World War II [but] we all need to be truthful about our politicians at all times.

Good. Get your facts right, then.