Echoes and Memories: Foreword to “Churchill in Punch” by Gary Stiles

Churchill in Punch, by Gary L. Stiles (London: Unicorn), 520 pp., $75 or £37.35 from Amazon USA or Amazon UK. In stock in Britain now; due in October in USA; order now to avoid a likely early sell-out and reprint delays.

Gary Stiles has produced an encyclopedic review of Sir Winston Churchill’s long career through the pages of Punch and its talented cartoonists. Every aspect of the long story is covered, and no Punch cartoon or image of Churchill is missed.

Gary Stiles has produced an encyclopedic review of Sir Winston Churchill’s long career through the pages of Punch and its talented cartoonists. Every aspect of the long story is covered, and no Punch cartoon or image of Churchill is missed.

Full disclosure: I assisted Dr. Stiles in vetting the manuscript. The following is excerpted from my Foreword (omitting references to cartoons found only in the book, with links to cartoons on this website or that of the Hillsdale College Churchill Project.)

The institution that was Punch

When the journalist Henry Mayhew and the wood-engraver Ebenezer Landells founded Punch (The London Charivari) in 1841, they created a long-lived feature of British life. A magazine of humour and satire, Punch was soon a “must-read” in political London. It appealed to visual as well as literary senses. According to Wikipedia, “it helped to coin the term ‘cartoon’ in its modern sense as a humorous illustration.”

Punch reached its apogee a century later, when its circulation soared to nearly 200,000. Readership declined when it became rather staid in the late Forties, and livelier periodicals multiplied. The editorship of Malcolm Muggeridge (1953-57) livened it up, but only for awhile. Punch ceased publication in 1992. It was revived in 1996, then closed for good in 2002.

Punch discovers Winston

Young Winston Churchill burst upon the UK scene in 1899, with his epic escape from a prison camp during the Second Anglo-Boer War. He rode his fame into Parliament, where his political impact captured the attention of Punch cartoonists. The young maverick was soon bucking his own Conservative Party on various issues. When he “crossed the floor” to the Liberals in 1904, his notoriety was secure. Punch artists, though, did not have personal control over how he was portrayed. “The subjects were decided by committee,” wrote Tim Benson of the Political Cartoon Society, “and not by the cartoonists themselves.”

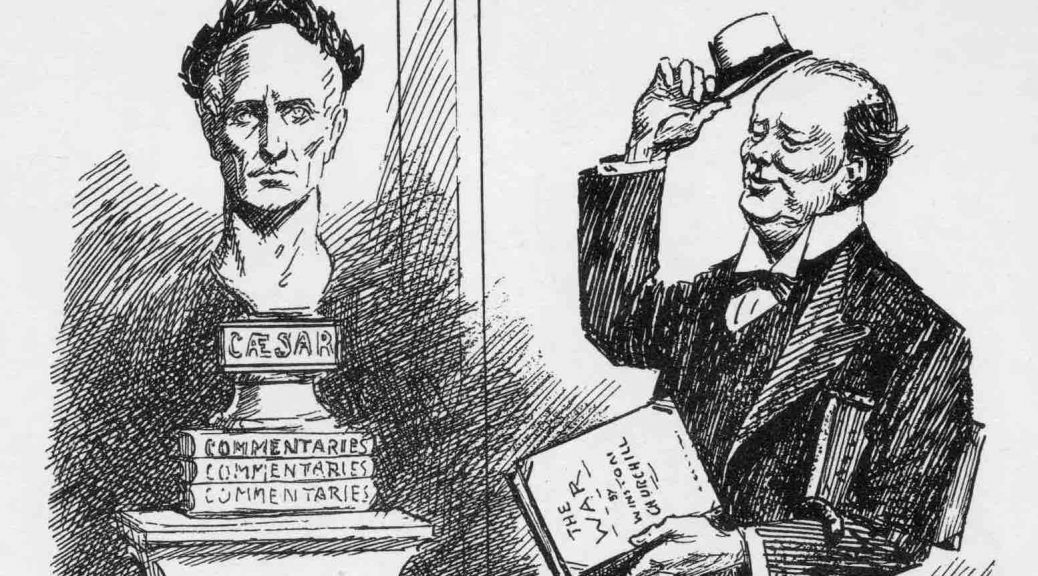

Early on, Punch cartoons were detailed pen-and-ink drawings, typified by those of chief cartoonist Bernard Partridge. They ably captured the new MP’s political skills and unbridled ambition. When a general election loomed, Partridge had Churchill offering his services as nothing less than prime minister (“Ready to Oblige,” January 1905)—even though he and his mentor, David Lloyd George, were relatively junior Liberals.

After the sweeping Liberal victory of 1906, young Winston’s stock rose rapidly. When he was appointed to the Privy Council, Punch artist Edward Tennyson Reed pictured him striding forward, eyes still on the premiership. At the same time, the American novelist Winston Churchill was also dabbling in politics. “I mean to be Prime Minister of England,” English Winston wrote him. “It would be a great lark if you were President of the United States at the same time.”

The young MP everybody seemed to know

Punch’s versatile artists were able to see the ironies and amusements of the “young man in a hurry.” By 1906 Churchill was Undersecretary for the Colonies, a non-cabinet position ordinarily of little import. But his superior, Lord Elgin, sat in the House of Lords, so Churchill at 32 became chief spokesman on colonial matters. Partridge cleverly portrayed their relationship in “An Elgin Marble” (April 1906).

In those early years politicians were portrayed less in caricature than in their actual appearance. Churchill came across as forceful and brash, wearing a sardonic grin and a shock of thinning hair. Drawn full length, his slim figure often assumed a stooped posture. Occasionally he was shown in fancy dress, referring to some position he took on the issues. But he was always recognizable—one of the few in Parliament known generally by his first name.

First World War

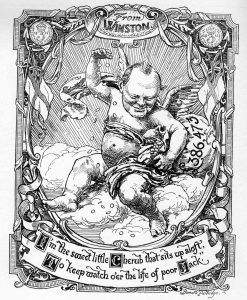

Phil May (1864-1903) is credited with moving the political cartoon from straitlaced Victorian drawings to humorous caricatures. These began cropping up in Punch around 1911, when Churchill became First Lord of the Admiralty. Approaching middle age he was balding and gaining a few pounds. Partridge brings out these features in the exaggerated, chubby cherub on his wonderful “Admiralty Christmas Card” (December 1912). Not mockery, the cartoon complimented Churchill’s concern for the pay and wellbeing of the Lower Deck.

Politically in those years, Punch trended Conservative, but was evenhanded toward the Liberal government headed by H.H. Asquith from 1908. Its Churchill cartoons commented wryly on his political machinations and continued prominence. Typical was Leonard Raven-Hill’s “Under His Master’s Eye” (May 1913), when Asquith tells him there’s been no “home news” since they’ve been off cruising on the Admiralty yacht. Churchill was now modernizing the Royal Navy, supervising its conversion from coal- to oil-fired warships. This was popular with both parties.

With the advent of war in 1914, Punch ran patriotic cartoons, avoiding bad news and the inevitable setbacks of conflict. Townsend welcomed the arrival of Admiral Jacky Fisher as Churchill’s First Sea Lord (“The Pilot,” November 1914). When WSC was sacked from the Admiralty over the Dardanelles fiasco in 1915, Punch showed a flapper suggesting that he enlist in the army. Churchill did just that, joining his regiment in Flanders in late 1915.

An easy study

After the Great War, more cartoonists moved to caricature, identifying their targets by exaggerated physical features or dress, as they still do today. Churchill in middle age was an artist’s delight: his cherubic countenance, receding hairline, oversize collars, cigars, bow ties and Astrakhan-collared greatcoats were exaggerated to maximum effect. A widely-circulated 1910 photo caught him wearing an absurdly small hat, which quickly became a trademark. Churchill’s hats fascinated cartoonists, as he himself wrote: “How many they are; how strange and queer; and how I am always changing them, and what importance I attach to them, and so on…. Well, if it is a help to these worthy gentlemen in their hard work, why should I complain?” After all, he explained, the worst fear of politicians is that cartoonists might stop noticing them.

A.W. Lloyd was Punch’s most adept caricaturist, taking humorous advantage of Churchill’s increasingly bulky figure. He made, for example, a perfect Tweedledum: the round face and almost bald pate, short stature and improbable garb. Lloyd’s art dominated Punch in the 1930s, with laughable sketches of the debates between Chancellors of the Exchequer: Labour’s Philip Snowden (another easily caricatured figure) and Churchill, his predecessor. “Everybody said that I was the worst Chancellor of the Exchequer that ever was,” WSC quipped. “And now I’m inclined to agree with them.”

Chief cartoonist Bernard Partridge (several cartoons with no byline may also have been his) stuck to his patented Edwardian sketches, but began now to cast subjects in imaginary poses with costumes representing their stance on the issues. Leonard Raven-Hill also produced lifelike images, almost always with improbable get-ups, from an organ-grinder to a prize-fighter .

Political wilderness

Beginning 1929, Churchill spent a decade in the political wilderness, spurned by his own party as often as by the opposition. Debate over the India Act found Punch supporting the new coalition government, while impugning its opponents including WSC (“The Rival Screevers,” November 1933). At first, Punch lampooned Churchill’s demands for rearmament in the face of Hitler (“A Streuthsayer or Prophet of Doom,” September 1934). But people took him more seriously as Germany armed. By the mid-Thirties Churchill’s warnings were not so easily set aside.

After the Munich settlement cast Czechoslovakia to the aggressor, Hitler’s intentions began seriously to alarm people. Punch reflected their changing opinion. In 1938, Churchill completed his epic biography of his ancestor the First Duke of Marlborough. Ernest Shepherd produced one of the most famous Punch cartoons of the day (“Family Visit,” November 1938). Here the ghost of Marlborough appears over Churchill’s shoulder, hoping his descendant will now also make history.

On the brink of war, Shepherd cast WSC as Sir Francis Drake, finishing his game of bowls and waiting for a summons to join the government. Churchill became First Lord of the Admiralty again, and Punch was now all for him. Its first Churchill cartoon of the war depicted him as Gilbert and Sullivan’s Joseph Porter in “HMS Pinafore” (“Ruler of the King’s Navee,” October 1939).

“Warden of the Empire”

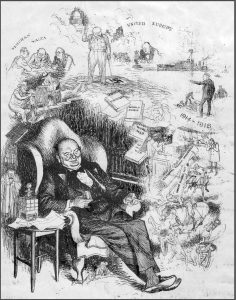

Churchill polled in the high 80% range during the war, and Punch remained in his corner through many reverses and disappointments. Lloyd’s cartoons invoked his familiar cherubic face and bald pate, but his expression was now serious and determined. Gone were the mockeries of large collars and tiny hats, but the cigar and bow tie remained. The visage was stern yet cheerful—“grim and gay,” as London cockneys put it in the Blitz: “What’s good enough for anybody is good enough for us.” Visiting the demoralized the French a week before they surrendered to Hitler, Churchill wrote: “I displayed the smiling countenance and confident air which are thought suitable when things are very bad.”

Lloyd’s Churchill image appeared often during the war, interspersed by the more realistic drawings of Bernard Partridge. In September 1940, Partridge documented the Atlantic meeting with Roosevelt, while E.T. Shepherd turned the PM into an ocean wave lashing the Nazi invaders. The fighting prime minister might appear as a bulldog, air raid warden, Egyptian or Viking warrior, Canadian Mountie, omnibus conductor, even the clock dial on St. Stephen’s Tower. Always he remained a figure to be admired.

Sometimes a cartoon would show him in one his favorite uniforms, like Elder Brother of Trinity House, Britain’s lighthouse authority (“Eleven-League Boots,” October 1944). In the previous war a French officer, puzzled by this get-up, asked Churchill what it signified. “Je suis un Frère Aîné de la Trinité,” WSC replied. “Mon dieu!” gasped the Frenchman. “La Trinité!?” Yet there was no mistaking the wearer: “Warden of the Empire,” as Shepherd dubbed him in May 1945.

Eclipse and revival

After 35 years as Punch’s chief cartoonist, Bernard Partridge died in harness in August 1945, replaced by E.H. Shepherd. On the staff now was a talented Welshman, Leslie Gilbert Illingworth, destined to produce some of the most famous (and infamous) postwar caricatures.

Punch now saw Churchill as more a statesman than a party leader, though WSC was a scintillating Leader of the Opposition. Shepherd’s drawings focused on his campaigns for Anglo-American alliance, European reconciliation, and his Second World War memoirs.

The 1945 Conservative defeat was almost reversed five years later, when Labour lost 90 seats, barely surviving with a small majority. Labour’s slim lead forced Prime Minister Attlee to call another election in October 1951, which put Churchill and the Conservatives back in power. Eisenhower was elected President in 1952, and cartoonists speculated on Churchill’s efforts to arrange a “meeting at the summit” with Ike and Stalin.

In 1953 Punch appointed as editor Malcolm Muggeridge, who had once declared, “there is no occupation more wretched than trying to make the English laugh.” So Mugg made them cry, almost immediately focusing on Churchill’s age and the need for a successor. The most likely candidates were R.A. Butler and Anthony Eden. Soon Illingworth, Cummings and other Punch cartoonists were drawing wrinkled, aged images of Churchill—and the aging Attlee with him.

The long farewell

Unbeknown to the public, a stroke felled Churchill in June 1953, and while he was “resting,” there was more talk of a successor. He made a fast recovery, though, and showed no sign of going—so Muggeridge and his editors decided to give him a push.

Illingworth’s cruel image of February 1954 was the most heartless Punch cartoon ever. Entitled, “Man Goeth Forth unto his Work and to his labour until the evening,” it showed a listless PM, hands swollen, jowls drooping. Churchill was bitterly affronted. “Yes, there’s malice in it,” he told his doctor. “Look at my hands—I have beautiful hands. Punch goes everywhere. I shall have to retire if this sort of thing goes on.”

In the event he held on, prominent in Punch during the debates over the Cold War, Britain’s nuclear deterrent, and in its regular feature, “Impressions of Parliament.” In June 1954, Cummings celebrated Churchill’s appointment as a Knight of the Garter. Six months later Ronald Searle depicted Parliament’s birthday present, a painting by Graham Sutherland which Sir Winston despised.

80 years on

The magazine devoted its 1 December 1954 cover and 33 images to Churchill’s career. In the same issue Illingworth made amends (“Happy Birthday to You”). But WSC is in bed. The pointed message was still there. Sir Winston was long past his “sell-by date.”

The PM memorialized his old leader, David Lloyd George, in his final speech in the House of Commons. He finally retired on 5 April 1955. The next day, Punch mocked-up the hated Sutherland painting, replacing Churchill’s head with that of his successor, Anthony Eden. (Eden now looked equally decrepit.)

Punch continued sporadically to notice the man who had dominated its pages and sold so many copies for six decades. In Moscow in 1956, Nikita Khrushchev denounced Stalin; Ronald Searle showed an aging Churchill reading the news, wondering if that might one day happen to him. Considering the arrant nonsense and blatant lies circulating about Churchill nowadays, one is glad that process took so long.

“Echoes and Memories”

As for Punch, the magazine was still remembering him with appreciation on his 85th birthday in 1959. Given all the ink it had devoted to him over the years, it barely noticed Churchill’s passing in 1965 . There was virtually nothing when he died, though a cartoon by Bernard Hollowood noted the mark he had left: A motorist asking for directions is told, “Keep left along Churchill Avenue, turn into Churchill Way past Churchill Airport and Churchill Station—and Churchill House is smack in front of you.”

Colophon

By then the ultimate cartoon accolade was long on record—and makes a worthy colophon to this book. That was “Member for Woodford” (November 1949)—a warm and generous portrayal of the Great Man and his unprecedented career.

Drawn by Leslie Illingworth, it represents Punch’s querulous, hilarious, wry yet respectful attitude toward Winston Leonard Spencer Churchill. Every time I see it, I am reminded of Prime Minister Harold Wilson’s words to Parliament after WSC’s death:

“For now the noise of hooves thundering across the veldt; the clamour of the hustings in a score of contests; the shots in Sidney Street, the angry guns of Gallipoli, Flanders, Coronel and the Falkland Islands; the sullen feet of marching men in Tonypandy; the urgent warnings of the Nazi threat; the whine of the sirens and the dawn bombardment of the Normandy beaches—all these now are silent. There is a stillness. And in that stillness, echoes and memories…. Each of us has his own memory, for in the tumultuous diapason of a world’s tributes, all of us here at least know the epitaph he would have chosen for himself: ‘He was a good House of Commons man.'”

With Churchill in Punch, Gary Stiles and Punch’s artists renew those echoes and memories for future generations.