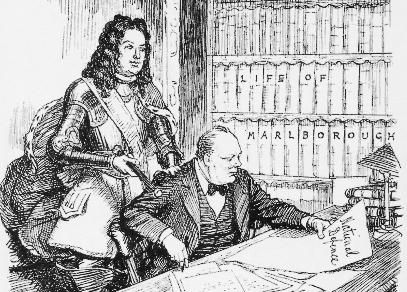

How Churchill Polished and Improved His Writing by Constant Revision

Condensed from “Constant Revision,” an article under my pen name for the Hillsdale College Churchill Project. For the complete text click here.

Revision and redraft

We are asked: “As I recall Churchill labeled his manuscripts something like “draft,” “almost final draft” and “final draft.” Do you recall what those categories were?”

We cannot establish that he routinely used those labels. Instead he tended to use “revise” or “revision.” Frequently his finished draft was marked “final revise.” It often took a long time before, with a sigh of relief, his private office staff reached that point. But the amount of revision varied with the project.

Whether the product was profound or simple, his first iteration was close to the mark. Grace Hamblin, a longtime secretary, recalled: “His dictation wasn’t difficult because it was very, very slow and he weighed his words. As one knows he had a tremendous command of the English language, but he didn’t use it loosely. He considered very carefully what he was going to say.”

Articles

Churchill’s articles saw less revision than his books and speeches. He wrote over 2000, notably in the 1930s, when constant income was needed to sustain his expensive lifestyle. In Artillery of Words, Frederick Woods wrote that some articles “were unashamed potboilers [which] sometimes sank to the level of ‘Are there Men on the Moon?’ and ‘Life under the Microscope.’” But others, like “Mass Effects in Modern Life” and “What Good’s a Constitution?” were profound reflections on statesmanship and government—both of the present, and (with some foreboding) the future. In Churchill Style, Barry Singer notes that during his 1931-32 North American lecture tour, Churchill contracted for twenty-two magazine articles. Ultimately “they would generate income in excess of £40,000.”

Michael Wolff, in a thoughtful introduction to Churchill’s Collected Essays, says his articles offer “the authentic Churchill in a way that can otherwise only be captured in his speeches.” His method of composition didn’t vary, Wolff writes. But assembling a major history or memoir was far removed “from the original Churchillian utterances as he dictated the first paragraphs in the middle of the night perhaps many months before…. But Churchill was never a dull man, was almost incapable of writing or speaking a dull sentence, and his ideas were nearly always imaginative.”

“Delayed-fuse chortle”

Robert Lewis Taylor’s excellent biography, Winston Churchill: An Informal Study of Greatness (1952), highlights another purpose of Churchill’s articles—influencing public opinion: For magazines in England and America, Taylor wrote,

he spoke up with authority on subjects high and low, but always at high prices. Collier’s was the outlet for most of his American articles. He struck some provocative notes. In one issue he casually predicted the return of silent movies, basing his stand on the enjoyment he recently had derived from a film of Charlie Chaplin’s. The piece was, in fact, substantially a minute biography of the comedian, with side lights on pantomime, then and now. Churchill gave credit for the art to the Emperor Augustus, and added that “Nero practiced it, as he wrote poetry, as a relaxation from the more serious pursuits of lust, incendiarism and gluttony.”

Many Collier’s readers took the notion, right or wrong, that the great statesman was hitting his ripest vein—a kind of genteel, delayed-fuse chortle—in the pages of the popular weekly. The humor that would seem ill timed in a history of war, or a treatise on his father, often sprang into joyous life in his rapid-fire potboilers.

Social media, 1930s style

Today, people read more social media than lengthy articles. Similarly, Churchill noticed the “popular press” replacing long newspaper columns of speech transcripts. After the First World War, wrote Michael Wolff,

it was not enough to appeal to the country through verbatim reports of speeches in the columns of The Times or the Morning Post…. Churchill felt that he had to address himself directly to the new electorate, taking the battle against Socialism and Communism straight into working-class homes…. So it is that we find him writing in a new style for popular Sunday newspapers [and] in the years leading up to the Second World War, for the News of the World and the Sunday Chronicle as well…. But more than anything, Churchill—rejected, as it seemed, by the “establishment”—needed a new audience and a new political base….

Does that not remind us of the Twitter and Facebook campaigns of modern politicians? Some, apparently, are as aware of the changing face of communication as Churchill was a century ago.

Speeches

Churchill took more pains with his speeches than his articles. Once he told his grandson they required “one hour of prep for each minute of delivery.” That was normally an exaggeration, though his great war speeches might have taken that kind of time. He dictated, as secretaries took his words in shorthand. Typed drafts saw revision after revision. Finally came “Speech Form,” with each passage picked out by indents. Grace Hamblin remembered that

the difficulty was to know which word he really meant you to put down. You would hear him mutter so often the same phrase in a different way. You could easily put him out if you entered a line in the wrong place. Also he had a way of shortening his words. “Ch of Exch” meant Chancellor of the Exchequer, but “C of E” meant Church of England. I once transposed them. My most notable mistake was when he’d dictated “tenure of office” and I wrote “ten years of office”…. You can imagine what he said about that!

Books

Churchill constantly revised his books, before, during, and after publication. Inevitably they went through multiple impressions, issues and editions, so he had ample opportunity. Frederick Woods wrote:

Revise would follow revise, eventually to become a “Final Revise”; this title, however, rarely fulfilled its promise. More often than not “Overtake Corrections” then began to arrive, sometimes even after the presses had started running. For his memoirs of the Second World War, this complex process resulted in a situation whereby Volumes II and IV had, respectively, two and three complete and variant texts.”

This writer remembers another secretary, Elizabeth Nel, saying, “We all heaved a sigh of relief when asked to type the ‘final revise.’” But that wasn’t the end of it. The publishers heaved an even bigger sigh after waves of “overtakes.” Jock Colville, a personal private secretary, said WSC was one of the few authors for whom publishers tolerated two or three complete reprints of page proofs.

Further reading

Richard M. Langworth, “How Churchill Saw the Future: Prescient Essays from Thoughts and Adventures.”

Richard M. Langworth, “Churchill’s Collected Works.”

Justin D. Lyons, “Churchill’s Trial: Winston Churchill and the Survival of Free Government by Dr. Larry P. Arnn.”

Video: Dr. Larry P. Arnn, “Churchill as a Defender of Constitutionalism.”