Novelist and Statesman: The Two Winston Churchills

Booksellers specializing in Sir Winston S. Churchill are still frequently offered books by Winston Churchill the American novelist. Their relationship is worth a passing glance.

Novelist Winston: early parallels

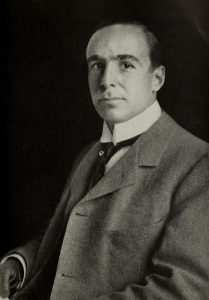

Winston Churchill was born in St. Louis, Missouri on 10 November 1871 and educated in the city’s public schools (“public” in the American sense, “state schools” in the British sense). In 1894, a year before his English counterpart graduated from the Royal Military College (now Academy) at Sandhurst, Churchill graduated from the United States Naval Academy at Annapolis. After the Naval Academy, he served briefly on the editorial staff of the Army and Navy Journal.

In 1895, when English Winston was paying his first visit to the United States, American Winston became managing editor of Cosmopolitan magazine. Three decades later, English Winston would begin a lengthy series of articles for the same journal.

First contacts

The two Churchills became aware of each other in 1900 when books by the English author began to appear alongside those of the already-well-established American. Indeed, so prominent was the American novelist at the time that English Winston wrote him a polite letter promising to use his middle name “Spencer” to distinguish himself from the far better-known American. The novelist replied that if he had a middle name he would have been pleased to return the compliment. Although English Winston soon dropped “Spencer,” he forever after used the byline “Winston S. Churchill.”

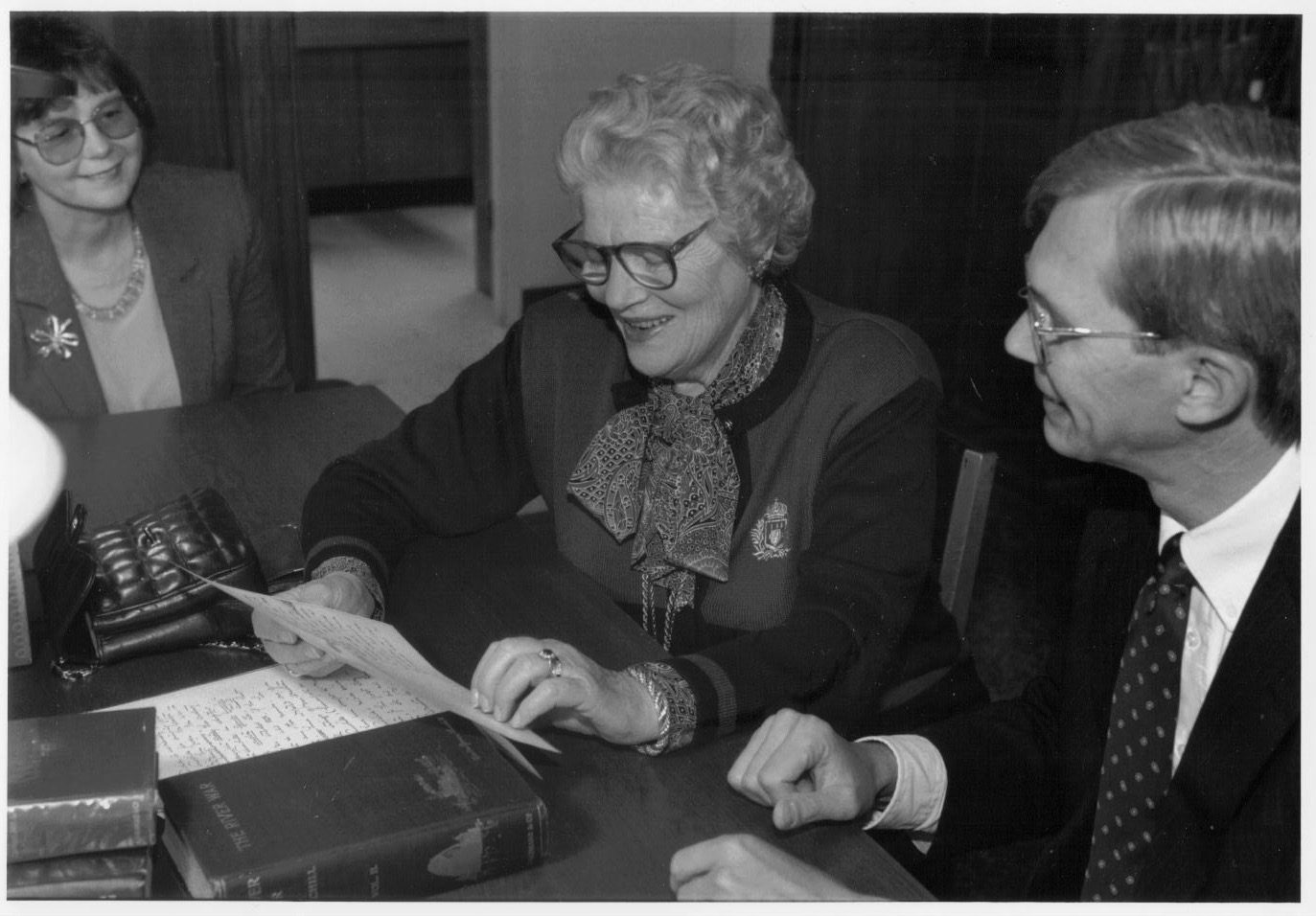

The amusing correspondence between them (“Mr. Winston Churchill to Mr. Winston Churchill”) appears in English Winston’s autobiography, My Early Life. In 1995, on one of her visits to us in New Hampshire, my wife and I took Lady Soames to the Baker Library at Dartmouth, which houses novelist Churchill’s papers. There she was able to review her father’s original letters to his eponymous fellow writer.

Political connections…

In 1901, the novelist Churchill and war correspondent Churchill met in Boston during English Winston’s lecture tour. American Winston threw a dinner for him. Great camaraderie prevailed and each of them promised there would be no more confusion. Alas, English Winston got the dinner bill and American Winston received English winston’s mail.

In Boston the two Churchills strolled the bridge over the Charles River and English Winston had an idea for his American friend. “Why don’t you go into politics? I mean to be Prime Minister of England. It would be a great lark if you were President of the United States at the same time.” Several years later the novelist was elected to the New Hampshire legislature. That was, alas, as far as he got, losing a campaign for reelection in 1906.

American Winston was an early recruit of the famous artist and writer colony at Cornish, New Hampshire, an “aristocracy of brains” founded by Augustus Saint-Gaudens in the 1890s. Among its distinguished cadre, Cornish counted illustrators Stephen and Maxfield Parrish, the garden designer Charles A. Platt, and artists Kenyon Cox, Florence Scovel Shinn and Willard Metcalf. Statesmen, notably Theodore Roosevelt, were among its visitors.

…and divergences

The two Churchills were not political soulmates. This is suggested by American Winston’s close friendship with Theodore Roosevelt. In 1911, American Winston ran for Governor of New Hampshire on the ticket of TR’s Bull Moose Party, but was not elected. TR nursed a famous antipathy toward both Winston Churchill and his father.

I believe, but cannot prove, that Roosevelt’s influence had something to do with the two Churchills’ lack of contact as the 1900s wore on. When American Winston visited London during World War I, to interview leading statesmen for his only non-fiction book, A Traveller in Wartime, he paid no call on English Winston.

Continued confusion

On another of Lady Soames’s visits, we took her to the grand Mount Washington Hotel in Bretton Woods, New Hampshire. Beforehand I warned her: “The Mount Washington believes your father stayed there in 1906. Of course it was the ‘other’ Winston Churchill, the American novelist. But don’t spoil their fun.” “Certainly not,” she said primly.

No sooner was she introduced to the manager than she piped up. “I understand you think my Papa was here in 1906. I’m sorry, dear, that is just not possible. That was, you know, the American Churchill. I’m told he was running for Congress at the time. I believe he lost.” (Then she looked at me and winked.)

Books by the novelist

English Winston published only one novel, Savrola. American Winston devoted almost his entire career to fiction. His books are still commonly found in dusty corners of New England secondhand bookshops. His work is rich in the panoply of 19th century American history and New England politics. Titles include Richard Carvel, The Inside of the Cup, A Modern Chronicle, A Far Country, The Crossing, The Title Mart, The Celebrity, Mr. Crewe’s Career, and a notable Civil War novel, The Crisis.

American Winston died in Florida on 12 March 1947, a few weeks after the death of English Winston’s brother Jack. I have been unable to find, but would be delighted to know of, anything he had to say about English Winston in the Second World War.

The Crisis

The two Churchills were alike in their appreciation for the heroism and sacrifice of the American Civil War. In The Crisis, Churchill the novelist offers an epic tale of that war. He depicts the tragedy and the glory it brought to Federals and Confederates alike. He explained some of his feeling about the book in an Afterword, which reads in part:

The author has chosen St. Louis for the principal scene of this story for many reasons. Grant and Sherman were living there before the Civil War, and Abraham Lincoln was an unknown lawyer in the neighboring state of Illinois. It has been one of the aims of this book to show the remarkable contrasts in the lives of these great men who came out of the West….

St. Louis is the author’s birthplace, and his home—the home of those friends whom he has known from childhood and who have always treated him with unfaltering kindness. He begs they will believe him when he says that only such characters as he loves are reminiscent of those he has known there.

The Crisis was in print longer than any of American Winston’s other books. It may have survived so long because people ordered it mistaking it for English Winston’s The World Crisis. As a historical novel, it deserves to stand on its own among other great works of its type. American Winston said his book spoke of a time

when feeling ran high. It has been necessary to put strong speech into the mouths of the characters. The breach that threatened our country’s existence is healed now. There is no side but Abraham Lincoln’s side. And this side, with all reverence and patriotism, the author has tried to take. Yet Abraham Lincoln loved the South as well as the North.

Churchillian parallels

Here then is another interesting convergence between the two Winston Churchills. Each shared a admiration for the nobility and sacrifice of the Blue and the Grey. Both honored the unifying genius of Abraham Lincoln. The novelist praises Lincoln’s love for the South as well as the North. He ends The Crisis with the immortal words of Lincoln’s second inaugural address:

With malice toward none, with charity for all, with firmness in the right, as God gives us to see the right, let us strive on to finish the work we are in; to bind up the nation’s wounds; to care for him who shall have borne the battle, and for his widow and his orphan—to do all which may achieve and cherish a just and a lasting peace, among ourselves, and with all nations.

Winston Churchill the Englishman also quoted those indelible words—in other contexts but with equal fervor.