Old Kerfuffles Die Hard: The Churchill Papers Flap is Back

“Boris Johnson, who has sought comparison with Winston Churchill, denounced spending national lottery money to save the wartime leader’s personal papers for the nation,” chortled The Guardian in December. (The Churchill Papers cover 1874-1945. Lady Churchill donated the post-1945 Chartwell Papers to the Churchill Archives in 1965.)

In April 1995 Johnson, then a columnist for the Daily Telegraph, deplored the £12.5 million purchase of Churchill Papers for the nation. The lottery-supported National Heritage Memorial Fund, said Johnson, was frittering away money on pointless projects and benefiting Tory grandees. Johnson added: “…seldom in the field of human avarice was so much spent by so many on so little …”

The Memorial Fund replied the Churchill Papers were a national heirloom under threat of being sold outside the country. Johnson snorted that they had simply “run out of sporting and artistic projects to endow.” His “unsentimental approach to Churchill’s records may seem surprising given that in 2014 he published a eulogistic biography of the former Conservative premier,” wrote The Guardian.

I remember the Great Churchill Papers Flap very well, having published articles about it back then. It is the same tempest in a teapot today that it was in 1995. Except that nowadays, Churchill and his memory are fair game to grunting mobs and virtue-signaling nannies. So the whole business is again somehow newsworthy.

A threat to Britain’s heritage

Sir Martin Gilbert, Churchill’s foremost biographer, called the Churchill Papers “the largest single private repository of recent British history.” Their acquisition, he said, was “an imaginative stroke of national policy.” Among other triumphs, the Papers inform thirty-one volumes of Winston S. Churchill, the longest biography on the planet.

Scholars have long mined these fifteen tons of documents. Many individual items have been reproduced. It was the possibility that they might be sold to an overseas buyer, Gilbert explained, that focused concern on their physical future:

The first alarm involved certain specific documents, such as Churchill’s wartime speeches, which clearly constitute part of the national heritage. Photocopies and reproductions are all very well, but the actual pieces of paper are what matters. The originals alone convey the full sense of historical drama.

The idea that Churchill’s final draft of “we will fight on the beaches” would end up in a library overlooking a beach in the Pacific, or some other distant shore, was not attractive. As a result of the decision to use National Lottery money to secure the Churchill Papers, it is not only letters written by Churchill that are to be preserved in this country and guarded, as hitherto, in the specially designed archives of Churchill College, Cambridge.

Sir Martin explained that “Churchill’s Papers” are very much more than his own notes and monographs. Of course they include handwritten or typed manuscripts of books and speeches, if not copies of his own letters. He also kept every letter that he received. “These letters, written to him, constitute the real historical value of this collection.”

A great glory saved

Churchill’s original letters reside in 500 libraries and archives around the world. The Churchill Papers, however, represent the whole range British history. Sir Martin offered examples:

Here we have letters from David Lloyd George, setting out the most radical proposals for social reform before the First World War. Here we have Lord Kitchener’s letters during the early months of the First World War, including the ill-fated Gallipoli expedition. We see here the Irish leaders on both sides struggling for a compromise to end the civil war. Here, too are Labour leaders negotiating with Churchill, then Chancellor of the Exchequer, to resolve the 1926 coal strike. Secretly, they visited him at a house in London to work out a compromise.

Throughout the 1930s the Churchill Papers abound in letters from civil servants, airmen and members of the intelligence community. They sent secret information, much of it from Nazi Germany, enabling Churchill to wage his campaign for greater rearmament. While his own letters consist in the main of carbon copies, it is the originals from other people that are the great glory of the papers saved for the nation.

A letter from his good friend Val Fleming (father of Ian) describes the slaughter on the Western Front. There is a letter from his brother Jack describing the first awful moments of the Dardanelles campaign. Letters from his mother, Lady Randolph Churchill, are full of the political gossip of 1916. There are letters from Admiral “Jackie” Fisher urging Churchill to return from the trenches and break the government. Churchill did return, but his efforts to harm the government in debate were a dismal failure.

A rich seam of historical gold

“The Papers represent every twist and turn of British political debate,” Sir Martin continued. Every file contains gems. “Having read and edited them all, I can only conclude that the Churchill archive will provide in the future, as it is already doing, a rich seam of historical gold.” It is the richest seam outside the Government’s own National Archives, which house Churchill’s voluminous war papers, and those of his four-year peacetime premiership.

(Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec, public domain)

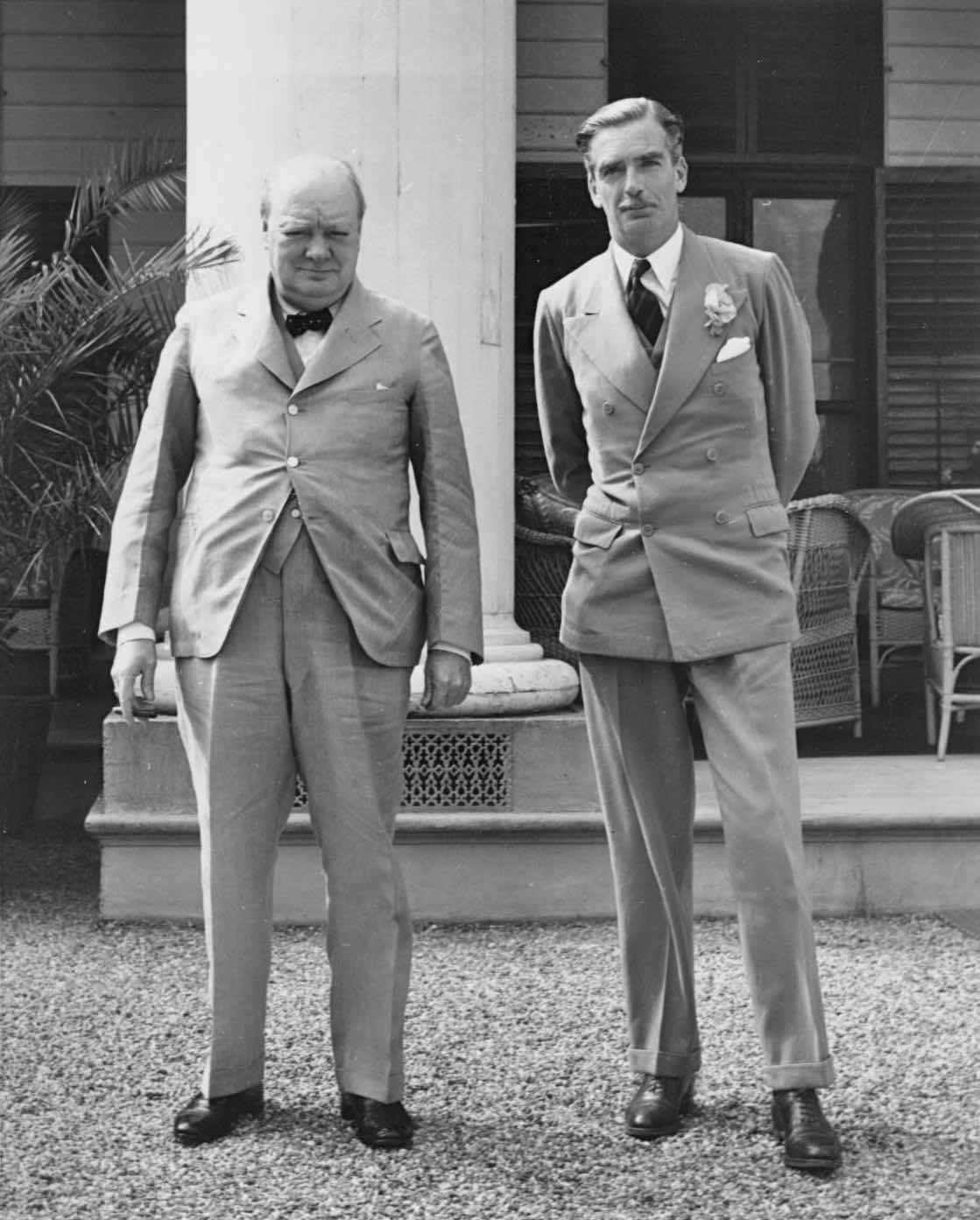

Every VE-Day, the Churchill Papers are there to prompt remembrance of heroic times. A letter on VE-Day itself was sent to WSC from Anthony Eden: “All my thoughts are with you on this day which is so essentially your day. It is you who have led, uplifted and inspired us through the worst days. Without you this day could not have been.”

And among the hundreds of letters from Churchill’s children is one from his daughter Mary, written when he was an old man long parted from power or influence: “In addition to all the feelings a daughter has for a loving generous father, I owe you what every Englishman, woman and child does, Liberty itself.” For this reason alone, Sir Martin concluded, “the assurance that the Churchill Papers are to remain in Britain is to be welcomed.”

Controversy and rebuttal

Remarkably in view their importance, some historians and media were outraged that one-fourth of the Churchill Papers’ value inured to private parties. They should have been donated, they said. On which, a few observations:

1) In later years, Churchill considered how he could provide for his family. Almost his only property of significant value was his papers. A typical Victorian, he willed them to his male heirs. However, as his daughter Mary told me, “all his dependents were provided for, and all were appreciative of what he did for them.”

2) Appraisals of the papers were £40 and £32.5 million respectively. The government took the lower estimate, subtracted £10 million for anything official and £10 million for tax. That left £12.5 million. J. Paul Getty II generously put up £1 million and the Heritage Lottery Fund £11.5 million—a fraction of their value on the open market.

3) Taxpayers did not provide the £11.5 million. Lottery profits go to various sports, arts, charities and Heritage materials. Almost always, Heritage items are in private hands, so their acquisition often benefits private parties.

4) Comparisons to the post-1945 papers left to Churchill College are irrelevant. Lady Churchill bequeathed them late in life, knowing her children had been provided for. Had she been younger she could have sold them, and would have had every right to do so.

5) While the copyright was retained (to documents originated by WSC), this should be kept in perspective. Until Hillsdale College took them on, no publisher would underwrite the final document volumes. Academic publications, non-profit institutions, even hostile biographers, have used the material without charge.

Why the uproar?

The reason for the flap has nothing to do with the rights of ownership, and everything to do with making political hay and sowing scorn. Such activities have vastly multiplied in the last quarter century. The biographer William Manchester was well aware of this when he memorably wrote The Times in 1995:

The controversy over the sale of the Churchill Papers to the British nation, with proceeds going to members of his family, is bewildering. One British historian in a U.S. newspaper labeled the transaction “just tacky.” One wonders why it is even newsworthy.

When out of office, Churchill, a professional writer, supported his household with his pen. His literary estate was his property. He had every reason, both moral and legal, to expect that title to it would pass on to his survivors through the trust fund which he established before his death. The sum of £12.5 million, however raised, seems hardly excessive. The collection would sell for far more than that in the United States. But that would have raised a genuine storm, which would have been justifiable.

Some critics believe that the Papers should have been donated to the country. That has a familiar ring. Authors are forever being told that they should give their work to society—that to expect money in return is, well, tacky. The origin of this presumption lies in a misapprehension of the word “gifted.” Many believe that talent is literally a gift, which the writer should pass along. The fact is that writing is very hard work, and that here, as elsewhere, the laborer is worthy of his hire. Surely any working person should be able to understand that.

One thought on “Old Kerfuffles Die Hard: The Churchill Papers Flap is Back”

I have been researching the life of my grandfather H. Gordon Thompson and I have a photo of him with Lady Churchill and Field Marshal Chetwode at an event to support the Red Cross Hospital Aid to China in about 1940. I cannot find any other reference to this. Could you give me any advice on where to look.

–

There is no mention of Gordon (or H. Gordon) Thompson in our digital canon of 80 million words by and about Churchill, but quite a few for Field Marshal Chetwode, whom you can find on Wikipedia.

Was your grandfather involved with the British Red Cross? Chetwode was Chairman of the Executive Committee of the War Organisation of the Red Cross and St John. It was he who formed the Aid to Russia Sub-Committee, of which he would be Chairman, and Clementine Churchill vice-chairman. Also try the Churchill Archives Centre. RML

Comments are closed.