In Search of Winston Churchill’s First Political Cartoon

First Cartoon? The Current Contender

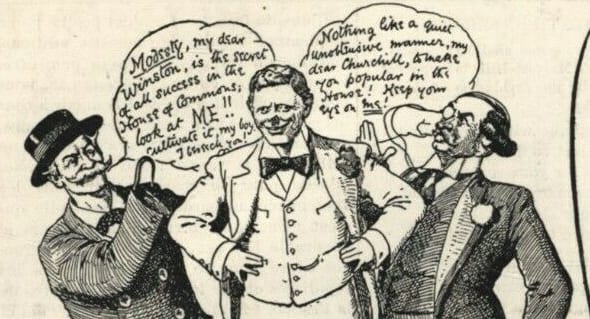

We are asked: what was the first Winston Churchill political cartoon? The earliest discovered so far is this one, from the “Essence of Parliament” column in Punch on 5 December 1900. It appeared about two months after young Winston was elected Member of Parliament for Oldham, Lancashire, on 1 October. Alas the cartoon (artist unknown) poses more questions than it answers. Churchill is being urged to exhibit modesty, a quality he was not known for. But who is doing the urging? We asked several authorities.

I first thought the man at right might be Joseph Chamberlain, known for his monocle. The “Great Joe” was an early mentor of Churchill, though they soon divided over Free Trade. But Andrew Roberts points out that Chamberlain had a slimmer build and never wore a moustache. Also, his boutonniere is not Chamberlain’s signature orchid, but what looks like a carnation.

And who is the chap at left, who has his right hand replaced by a hook? We asked Lord Dobbs, author of several fine Churchill novels. He referred to Lord Baker, former Home Secretary and Chairman of the Conservative Party, who has an interest in political cartoons.

Lord Baker kindly searched for MPs with disabilities and found Michael Davitt, Irish Party, who last served as MP for South Mayo in 1895–99. Davitt had lost his right arm at the age of eleven. He became a prominent member of the Fenian movement, Lord Baker writes. “There are photographs and statues, but they do not show a hook and the sleeve of his coat was left empty.”

None of the Above?

Davitt left Parliament in 1899, but might fill the bill. He did sport an elaborate moustache, though the cartoon figure is older than his Wikipedia photo. Perhaps he’d gone grey—he died aged only 60 in 1906. Was Michael Davitt still notorious enough to get into cartoons in 1900? Did he wear bell-bottom trousers? I don’t know. Also, Davitt appears nowhere in Churchill’s books, speeches, letters and papers. We can find no Churchill relationship, except that both were sympathetic to Irish Home Rule.

Is this cartoon number 1? It seems likely that Oldham if not London journals published Churchill cartoons when he was first campaigning, in summer 1899. (Remember, 1900 was his second attempt at office. His first ended in defeat in July 1899.) His image might have appeared in the papers then.

Another expert consulted was Tim Benson of the Political Cartoon Society in London. He agrees with Andrew Roberts that the righthand figure is not Joseph Chamberlain, but has no conjecture on either figure. Tim believes this is not the first political cartoon. He recommends a journal called Judy and Fun, which we couldn’t find on the web.

Punch, happily, is archived online, but this too presents problems. Searching for “Churchill” digitally produces five references in 1900: two to Lady Randolph Churchill, two on Winston’s escape from the Boers, and one on WSC addressing Oldham voters. But the search engine does not apply to images. We’d have to sift through 1899 and 1900 page by page. Fortunately Mr. Gary Stiles, who is publishing a book of Punch Churchill cartoons, has sifted already and assures us that 5 December 1900 saw the first cartoon in the famous magazine.

Earlier non-political cartoons

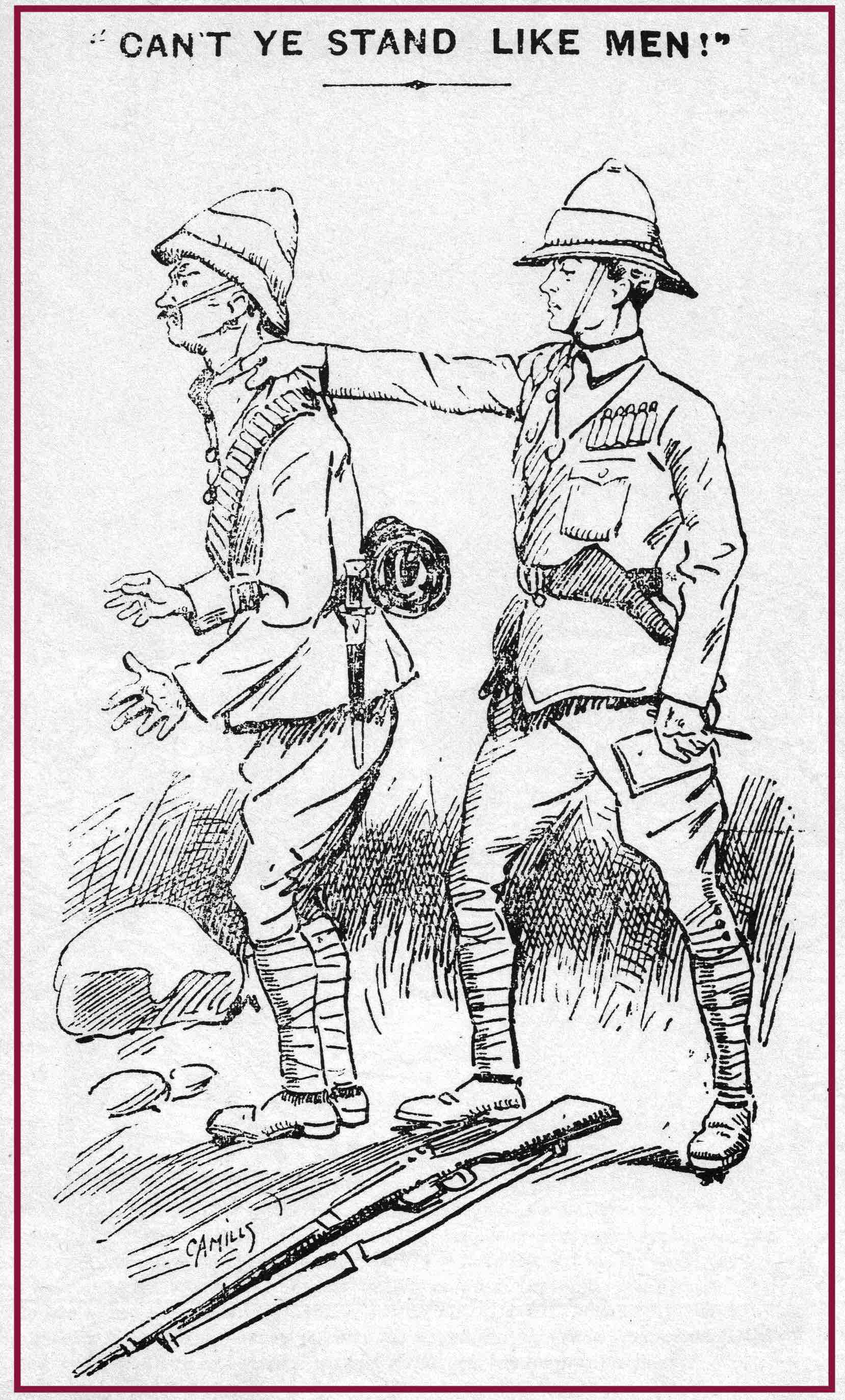

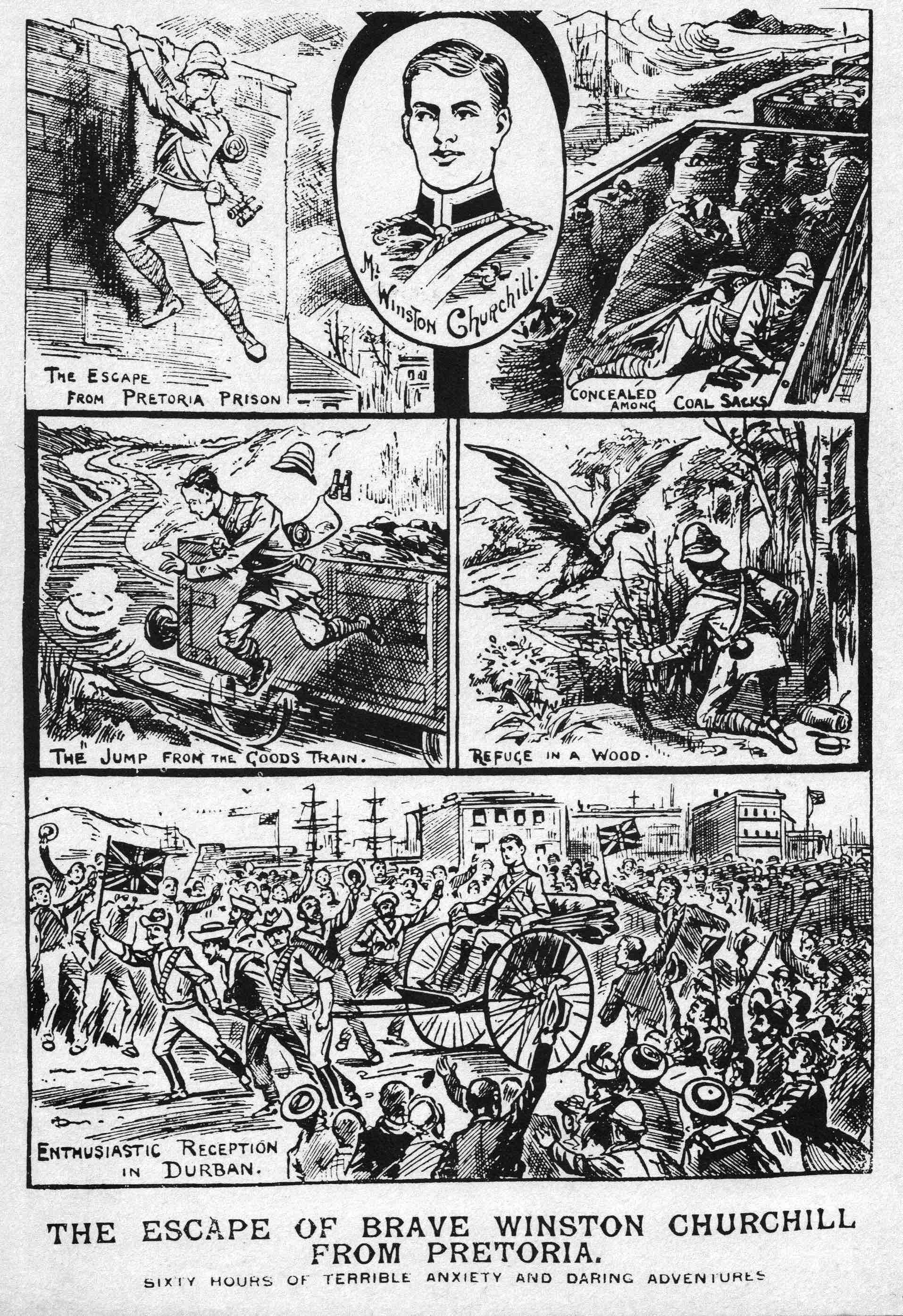

Churchill first achieved notoriety in the Second Boer War, when went he went “over the wall” and escaped the POW camp in Pretoria. He’d been sent there after helping British defenders in the famous armoured train incident. Arrested, he claimed he was a war correspondent. The Boers reasonably asked, then why was he among the British combatants?

Churchill’s response was to escape, leaving a jaunty note to M. de Souza, the Boer Secretary of War. For general amusement, I reproduce it here from my book of quotes, Churchill by Himself:

Sir,—I have the honour to inform you that as I do not consider that your Government have any right to detain me as a military prisoner, I have decided to escape from your custody. I have every confidence in the arrangements I have made with my friends outside, and I do not therefore expect to have another opportunity of seeing you.

I therefore take this occasion to observe that I consider your treatment of prisoners is correct and humane, and that I see no grounds for complaint. When I return to the British lines I will make a public statement to this effect. I have also to thank you personally for your civility to me, and to express the hope that we may meet again at Pretoria before very long, and under different circumstances.

Regretting that I am unable to bid you a more ceremonious or a personal farewell, I have the honour, to be, Sir, Your most obedient servant, Winston Churchill.

Naturally his colorful escape engendered various cartoons. But these were not political. So the search goes on.