Johnson, Trump…can we stop comparing everybody to Churchill?

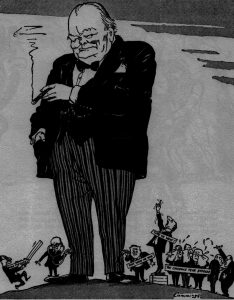

Politicians, like Boris Johnson and Donald Trump at the moment, are often compared to Winston Churchill. In a way it’s nice PR for Sir Winston. Half a century since his death, the Greatest Briton still dominates media. His Google hit count is 100 million. (Franklin Roosevelt, the West’s other great war leader, is at 72 million.)

Rightly or wrongly, every day on the Internet, Churchill is praised, lampooned, quoted and misquoted. But comparisons to modern politicians have worn thin. They may emulate him, but should not be compared to him.

Johnson’s Day in the barrel

On 15 June the Wall Street Journal focused on British prime minister in waiting Boris Johnson. Columnist Peggy Noonan wrote a perceptive piece about his prospects and challenges: “England Needs a Slap, and so does China.”

Aside from badly misrepresenting Churchill’s sobriety, she made good points. Boris Johnson’s friends, she wrote, are “have the grating habit of comparing him to Winston Churchill.” Grating is a good word. Mr. Johnson needs to talk to his friends.

Boris’s enemies adopted the same tactic after he was appointed Prime Minister on 24 July. Joyce McMillan in The Scotsman used Johnson’s own description of WSC in his Churchill biography to suggest they were peas in a pod:

“He wasn’t what people thought of as a man of principle. He was a glory-chasing goal-mouth-hanging opportunist…. As for his political career—my word, what a feast of bungling!…he was thought to be congenitally untrustworthy.”

The New York Times likened Johnson’s frequent allusions to the “Dunkirk spirit” in Britain’s exit from the European Union as a fetish: “The idea that Britain, acting alone, can exact favorable terms from much larger powers such as China, Europe or, indeed, the United States, is a delusion… Britain will become a middling provincial country, whose fortunes will be subject to the whims of others… Churchill would have been horrified.”

Since Britain is the world’s fifth largest economy, that is anything but a foregone conclusion. Nor does it suggest what Churchill really thought about a Britain within a federal Europe.

Next Mr. Trump

Then there’s Mr. Trump. His supporters extoll his Churchill characteristics: pugnacity, conviction, diehard devotion to causes and policies. Fans visualize him on Dover’s white cliffs, defying oncoming Democrat Messerschmitts and Dorniers. “We shall go on to the end…We shall never surrender.” (As far as I know, Trump has not yet proclaimed himself a Churchill, though he sometimes suggests he’s Lincoln or Washington.)

“Do you see any comparisons to the President?” I was asked recently. I waffled and gave a dusky answer. The question seemed so preposterous that it took me by surprise. Having now thought about it, yes, there are similarities—but also many differences.

Like Trump, Churchill said what he thought people should hear, straining nothing through advisors or focus groups. “Tell the truth to the British people!” he thundered in the 1930s as Germany armed. In war, he explained, they are “the only people who like to be told how bad things are, who like to be told the worst.” (For some three years, the worst was all he could tell them.)

Parallels and Divergencies

Like Trump and Johnson, Churchill often tackled the media: “A few critical or scathing speeches, a stream of articles in the newspapers, showing…how incompetent are those who bear the responsibility,” he said in 1933, “these obtain the fullest publicity.”

When the BBC threatened to censor his broadcasts he quipped: “We can picture [BBC director] Sir John Reith, with the perspiration mantling on his lofty brow, with his hand on the control switch, wondering, as I utter every word, whether it will not be his duty to protect his innocent subscribers from some irreverent thing I might say about Mr. Gandhi, or about the Bolsheviks…”

Abroad, however, Churchill was far more careful than Trump—and his predecessor. In London before the Brexit vote, President Obama said that if Britain left the EU it would have to go “to the back of the queue.”

Trump cheered the Brexit vote. In London in 2019 he endorsed Johnson for prime minister. (Another of his friends Boris needs to speak to?)

Churchill was very different. “When I am abroad I always make it a rule never to criticize or attack the government of my own country,” he said in 1947, when he was Leader of the Opposition. “I make up for lost time when I come home.”

Unlike Trump, Churchill abroad never took sides between foreign politicians. In Washington in 1954 he said, “I am not going to choose between Republicans and Democrats. I want the lot.” No foreign leader has said that for awhile.

Forget the Comparisons

Let’s be serious. We can’t compare Boris Johnson, Donald Trump, or anybody else to Winston Churchill. Superficial resemblances exist, but everything else overwhelms them.

My friend the college president has the best answer whenever anybody indulges in silly comparisons. I warmly recommend it to you, conscious that I intrude upon his copyright. When asked if “X” is like Churchill, Dr. Larry Arnn usually responds:

Winston Churchill served in four wars and wrote five books by age 25. He held every major office except foreign minister. Twice prime minister, he was politically prominent for fifty years. Writing fifty books he won the Nobel Prize for literature. He composed 4000 articles and speeches; in all he produced 15 million words. His official biography is thirty-one volumes, and there are a thousand books about him. Sure, X is just like Churchill.