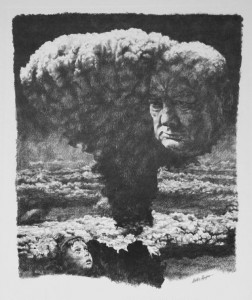

Bombing Japan: Churchill’s View

Scott Johnson of Powerline (“Why We Dropped the Bomb,” 13 April) kindly links an old column of his quoting an old one of mine with reference to President Obama’s visit to Hiroshima and the atom bombing of Japan.

Johnson links a lecture by Professor Williamson Murray, which is worth considering, along with Paul Fussell’s classic essay in The New Republic, “Thank God for the Atom Bomb,” which makes you think, though some consider it a rant. Fussell wrote:

John Kenneth Galbraith is persuaded that the Japanese would have surrendered surely by November without an invasion. He thinks the A-bombs were unnecessary and unjustified because the war was ending anyway. The A-bombs meant, he says, “a difference, at most, of two or three weeks.” But at the time, with no indication that surrender was on the way, the kamikazes were sinking American vessels, the Indianapolis was sunk (880 men killed), and Allied casualties were running to over 7000 per week. “Two or three weeks,” says Galbraith.

Two weeks more means 14,000 more killed and wounded, three weeks more, 21,000. Those weeks mean the world if you’re one of those thousands or related to one of them. During the time between the dropping of the Nagasaki bomb on August 9 and the actual surrender on the fifteenth, the war pursued its accustomed course: on the twelfth of August eight captured American fliers were executed (heads chopped off); the fifty-first United States submarine, Bonefish, was sunk (all aboard drowned); the destroyer Callaghan went down, the seventieth to be sunk, and the destroyer escort Underhill was lost.

That’s a bit of what happened in six days of the two or three weeks posited by Galbraith. What did he do in the war? He worked in the Office of Price Administration in Washington. I don’t demand that he experience having his ass shot off. I merely note that he didn’t.

Bombing and Churchill

But back to Churchill. What did he think about the bombing? Need you ask. Churchill wrote in his war memoirs, Vol. 6, Triumph and Tragedy (1953, chapter 19):

British consent in principle to the use of the weapon had been given on July 4, before the test had taken place. The final decision now lay in the main with President Truman, who had the weapon; but I never doubted what it would be, nor have I ever doubted since that he was right. The historic fact remains, and must be judged in the after-time, that the decision whether or not to use the atomic bomb to compel the surrender of Japan was never even an issue. There was unanimous, automatic, unquestioned agreement around our table; nor did I ever hear the slightest suggestion that we should do otherwise.

Some historians have cited a minor official in the Foreign Office who argued that Japan would surrender without the bombing, if the Allies promised she could keep her emperor; it was never proven that this ever reached the plenary level. Others quibble that the first bomb (Hiroshima) was perhaps necessary, but surely not the second (Nagasaki) only three days later, after the effects of the first were not even assessed. But the Japanese cabinet was divided still on the question of surrender after Nagasaki. Churchill continued:

I had in my mind the spectacle of Okinawa island, where many thousands of Japanese, rather than surrender, had drawn up in line and destroyed themselves by hand-grenades after their leaders had solemnly performed the rite of harakiri. To quell the Japanese resistance man by man and conquer the country yard by yard might well require the loss of a million American lives and half that of British—or more if we could get them there: for we were resolved to share the agony.

Now all this nightmare picture had vanished. In its place was the vision—fair and bright indeed it seemed—of the end of the whole war in one or two violent shocks. I thought immediately myself of how the Japanese people, whose courage I had always admired, might find in the apparition of this almost supernatural weapon an excuse which would save their honour and release them from being killed to the last fighting man.

Truman never shrank from decisions, and in this one he was right. Six years of war (ignorant Americans always forget and say four) was enough. In 1953, Acheson placed Churchill “on trial” for dropping those bombs, in a perhaps inappropriate banter, but with more serious implications.

*****

Wars are declared on nations, not those who lead them, which is one reason why declarations of war have gone out of fashion. In our more “enlightened” age we are repelled by the suffering war inflicts on ordinary people. Unfortunately, you can’t declare war on an individual.

In introducing Alistair Cooke at the 1988 Churchill Conference, I quoted the words of that caring and generous man on the 25th anniversary of the bombing, which I had long since committed to memory:

Without raising more dust over the bleached bones of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, I should like to contribute a couple of reminders: The first is that the men who had to make the decision were just as humane and tortured at the time as you and I were later. And, secondly, that they had to make the choice of alternatives that I for one would not have wanted to make for all the offers of redemption from all the religions of the world.

4 thoughts on “Bombing Japan: Churchill’s View”

I wish your campaign fortune. It would be an unmitigated blessing if mankind somehow, despite all its perennial flaws, universally agreed never to use what Churchill called “these awful agencies of destruction.”

War itself being a crime against humanity, it is a little redundant to identify specific parts of it as the same thing. I explained Churchill’s and Truman’s views, too superficially I fear, based on what they knew at the time.

Professor Williamson Murray, in a 2015 lecture at Ohio State, is more thorough, analyzing the bombing decision based on what we now know. Click here and skip to start at minute 7:

Murray reminds us that it’s a very frequent habit these days for historians and others to engage in Monday morning quarterbacking. What they often miss—when recommending what we should have done instead of what we did—is that it might have led to something even worse.

I found interesting his documentation that US (20,000) and Japanese (77,000) deaths in Okinawa, a three-month battle, were close to the number of Americans killed in all twelve years of the Vietnam War, not to mention Vietnamese; and that the estimate of “only” 50,000 U.S. casualties in taking Kyushu were made in May, when Japan had 100,000 troops there….by August Japan had 450,000, plus 5000 Kamikaze aircraft ready to go.

You are right to identify the threat of starvation, but perhaps not the extent of that threat—particularly if it was decided not to drop the bombs. By mid-1945, it was already known that knocking out transportation had been the most productive aspect of the air war on Germany. In an extended campaign in Japan, one of the first objectives would have been its transportation facilities, which were vulnerable and relatively easy to destroy. What would that have led to? It’s not hard to imagine:

By summer 1945, the Japanese were rationed to 1200 calories a day, the edge of starvation. As you state, the situation continued long afterward. Murray notes that even in 1946, General MacArthur (for once “the good MacArthur”) had to urge President Truman to send massive food aid or risk going down in history as the starver of 3-5 million people. Truman did so, and Japan’s transportation system was intact to deliver it. As a result a catrastrophe far worse, and longer lasting, was averted.

We must always, as they say, be careful what we wish for.

May I suggest visiting my website (My Hiroshima) at http://www.tsumura.co.uk to find whether the atomic bombings on Hiroshima and Nagasaki were necessary? I presume Churchill’s speech of justifying the bombings at the Parliament on August 16, 1945 helped shape the common view held by the British even today. The most important issue is that the atomic bombings, which killed indiscriminately hundreds of thousands of people, mostly civilians, were crimes against humanity, no matter how anyone tries to justify the bombings.

Ah, there’s the rub. The imminent entry of Russia into the war against Japan was a spur to Truman, who worried how far they might go. But the Japanese cabinet was still not unanimous for surrender after Nagasaki. It took the emperor, at risk of his life (indeed a coup was tried but failed), to decide to surrender.

Some beleive unconditional surrender for Japan was unnecessary. Well after Hiroshima the Russian declaration of war might have kneeled Japan for good, without Nagasaki.

Comments are closed.