Was WW2 Avoidable?

continued from previous post…

Churchill and the Avoidable War

Preface

This book examines Churchill’s theory that “timely action” could have forced Hitler to recoil, and a devastating catastrophe avoided. We consider his proposals, and the degree to which he pursued them. Churchill was both right and wrong. He was right that Hitler could have been stopped. He was wrong in not doing all he could to stop him. The result is a corrective to traditional arguments, both of Churchill’s critics and defenders. Whether the war was avoidable hangs on these issues.

Chapter 1. Germany Arming: Encountering Hitler, 1930-34

“There is no difficulty at all in having cordial relations between the peoples….But never will you have friendship with the present German Government. You must have diplomatic and correct relations, but there can never be friendship between the British democracy and the Nazi power….That power cannot ever be the trusted friend of the British democracy.” —Churchill, 1934

“There is no difficulty at all in having cordial relations between the peoples….But never will you have friendship with the present German Government. You must have diplomatic and correct relations, but there can never be friendship between the British democracy and the Nazi power….That power cannot ever be the trusted friend of the British democracy.” —Churchill, 1934

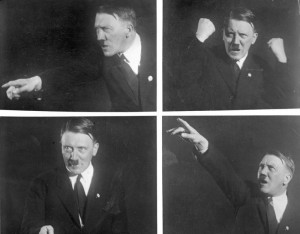

Some claim Churchill was “for Hitler before he was against him.” To say he admired Hitler is true in one abstract sense. He admired the Führer’s political skill, his ability to dominate and to lead. With his innate optimism he even hoped briefly that Hitler might “mellow.” But in his broad understanding of Hitler, Churchill was right all along: dead right.

Chapter 2. Germany Armed: “Hitler and His Choice,” 1935-36

Recently [Hitler] has offered many words of reassurance, eagerly lapped up by those who have been so tragically wrong about Germany in the past. —Churchill, 1935

It is widely stated that Churchill admired Hitler, to the point of suggesting that if Britain had been defeated it could have benefitted from someone like him. Herein we examine Churchill’s contentious essay, “Hitler and His Choice,” in the Strand Magazine, 1935. We also evaluate Churchill’s mid-1930s warnings of the perils of disarmament.

Chapter 3. The Rhineland :“They had only to act to win,” 1936

“Mr. Baldwin explained [to French Foreign Minister Flandin] that although he knew little of foreign affairs he was able to interpret accurately the feelings of the British people. And they wanted peace. M. Flandin says that he rejoined that the only way to ensure this was to stop Hitlerite aggression while such action was still possible.” —Churchill, 1948

Churchill later stated that Hitler could have been stopped when he marched into the Rhineland in 1936. This on the evidence is true. At the time, though, Churchill failed to press the issue. Hoping for office under Baldwin, who had become prime minister once again, he chose not to buck his party’s leader, clinging to a hope that the French would act alone; but they would not move without tacit British support.

Chapter 4. Derelict State: The Austrian Anschluss, 1938

“Europe is confronted with a programme of aggression, nicely calculated and timed, unfolding stage by stage, and there is only one choice open, not only to us, but to other countries who are unfortunately concerned—either to submit, like Austria, or else to take effective measures while time remains….” —Churchill, 1938

In 1935 Hitler assured Austria of her independence. In February 1938 he summoned the Austrian Chancellor in February 1938, demanding appointment of a Nazi Interior and Security Minister. In London, The Times stated that “no one but a fanatic” would believe this meant a “Nazified Austria.” A month later, Hitler proclaimed an Anschluss, or union with Austria. Churchill did not see this coming, though he had warned in a general sense, and his prescience was justified. Czechoslovakia, he predicted, would Hitler’s next conquest.

Chapter 5. Munich’s Mortal Follies, October 1938

“Silent, mournful, abandoned, broken, Czechoslovakia recedes into the darkness….I do not grudge our loyal, brave people, who were ready to do their duty no matter what the cost….but they should know the truth. They should know that there has been gross neglect and deficiency in our defences; they should know that we have sustained a defeat without a war, the consequences of which will travel far with us along our road.” —Churchill, 1938

The Munich agreement, which entrenched Hitler in power and gave him Czechoslovakia with its military factories, is held today the classic example of fatal appeasement. Yet a curious narrative has evolved that Munich was actually wise, since it gave the Allies another year to arm. Less often remarked is that it also gave Germany another year, and even German sources agree the Nazis were less formidable in 1938. What was there about fighting them in 1939-40 that made it preferable? Was it Hitler’s eradication of Poland in three weeks, the Low Countries in sixteen days, France in six weeks? This chapter also examines the credible 1938 plot to overthrow Hitler. After Munich the plotters despaired. Most were later executed.

Chapter 6. “Favourable Reference to the Devil”:

The Russian Enigma, 1938-39

“I cannot forecast to you the action of Russia. It is a riddle wrapped in a mystery inside an enigma: but perhaps there is a key. That key is Russian national interest. —Churchill, 1939

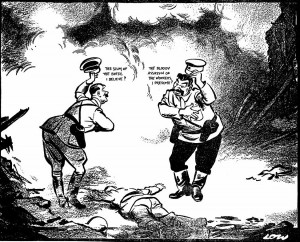

As Churchill predicted, Munich sealed Czechoslovakia’s fate. In mid-March 1939, Czech President Emil Hácha, threatened with the bombing of Prague, agreed to German occupation of the rest of his country, which was renamed the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia—an arrangement which “in its unctuous mendacity was remarkable even for the Nazis.” This chapter examines Churchill’s evaluation of the Soviet versus Nazi danger; his conclusion that the latter was the greater threat; his urgent efforts to encourage an understanding with the Russians; and the rebuff his prescriptions received by the British (and to some extent the Soviet) government.

Chapter 7. Lost Best Hope: The America Factor, 1918-41

“America should have minded her own business….If you hadn’t entered the war the Allies would have made peace with Germany in the Spring of 1917….there would have been no collapse in Russia followed by Communism, no breakdown in Italy followed by Fascism, and Germany would not have signed the Versailles Treaty, which has enthroned Nazism in Germany.”

Google this alleged 1936 quotation and you’ll find a half dozen citations unquestioningly attributing it to Churchill—a striking reversal of his off-stated view that America could not avoid “world responsibility.” As World War II approached these alleged words resurfaced. Churchill sued the perpetrator and won. How he handled this peculiar case illustrates his consistent belief that the United States could not isolate itself—and that with American support the war could have been prevented.

Chapter 8. Was World War II Preventable?

“Embalm, cremate and bury—take no risks!”

“Here is a line of milestones to disaster. Here is a catalogue of surrenders, at first when all was easy and later when things were harder, to the ever-growing German power. But now at last was the end of British and French submission. Here was decision at last, taken at the worst possible moment and on the least satisfactory ground, which must surely lead to the slaughter of tens of millions of people.” —Churchill, 1948

This chapter contrasts British, French and German rearmament between Munich and the outbreak of war. It also looks at Churchill’s failed efforts to promote collective security with Russia and the United States. It examines the lost year when Prime Minister Chamberlain rebuffed overtures by Stalin and Roosevelt. Meanwhile, Hitler secured his eastern flank with a Nazi-Soviet non-aggression pact.

Summary: What Churchill Teaches Us Today

“The word ‘appeasement’ is not popular, but appeasement has its place in all policy. Make sure you put it in the right place. Appease the weak, defy the strong. It is a terrible thing for a famous nation like Britain to do it the wrong way round…. Appeasement in itself may be good or bad according to the circumstances. Appeasement from weakness and fear is alike futile and fatal. Appeasement from strength is magnanimous and noble and might be the surest and perhaps the only path to world peace.” —Churchill, 1952

To her father’s admirers the late Lady Soames would always offer a commandment: “Thou shalt not say what my father would do today.” Modern situations are vastly different. The threat today is diffuse; in its totality it is by no means comparable to that embodied by Nazi Germany.

Was Churchill right that World War II was preventable? The answer is probably “yes—but with great difficulty.” Was he right that it is foolish to put off unpleasant reality “until self-preservation strikes its jarring gong”? Undoubtedly. The problem for leaders today is to judge when discretion should take priority over action, when diplomacy is yet a feasible option—and when and how to deploy a bluff.