“The Pool of England”: How Henry V Inspired Churchill’s Words

Excerpted from “Churchill, Shakespeare and Henry V.” Lecture at “Churchill and the Movies,” a seminar sponsored by the Center for Constructive Alternatives, Hillsdale College, 25 March 2019. For the complete video, click here.

Shakespeare’s Henry: Parallels and Inspirations

Above all and first, the importance of Henry V is what it teaches about leadership. “True leadership,” writes Andrew Roberts, “stirs us in a way that is deeply embedded in our genes and psyche.…If the underlying factors of leadership have remained the same for centuries, cannot these lessons be learned and applied in situations far removed from ancient times?”

Churchill’s war speeches are—what shall we say—inspired by, remindful of, analogous to Shakespeare’s works in ancient times. First example: the enemy’s overconfidence. At Agincourt, before any fighting takes place, as the French prepare to rout the English, the Duke of Orleans opines:

Foolish curs, that run winking into the mouth of a Russian bear

and have their heads crushed like rotten apples.

You may as well say that’s a valiant flea

that dare eat his breakfast on the lip of a lion….

It is now two o’clock: but, let me see, by ten

We shall have each, a hundred Englishmen.

Animal analogies are things Churchill deployed, but that is not the connection here. That passage smacks of his 1941 speech to the Canadian Parliament about the French generals in 1940. Remember how he quoted them? “In three weeks England will have her neck wrung like a chicken.” And his response: “Some chicken!. . .Some neck!”

1415…

At the siege of Harfleur, before Agincourt, Churchill writes in his History that the British were badly outnumbered, yet “foremost in prowess.” And Shakespeare quotes King Henry:

Once more unto the breach, dear friends, once more;

Or close the wall up with our English dead …

I see you stand like greyhounds in the slips …

Follow your spirit, and upon this charge

Cry “God for Harry, England, and Saint George!”

This is echoed in Churchill’s war memoirs, where he writes: “Once again we must fight for life and honour against all the might and fury of the valiant, disciplined, and ruthless German race. Once again. So be it.”

…1940

And in his peroration to his outer cabinet on 28 May 1940—the speech that ensured Britain would not seek an armistice with Hitler: “We shall fight on, and if this long island story of ours is to end at last, let it end only when each of us lies choking in his own blood upon the ground.”

Hugh Dalton remembered: Churchill’s ministers stood shouting, slapping him on the back, while tears poured down his cheeks, and theirs. A.P. Herbert wrote:

Mr. Chamberlain, after all, was tough enough, and since the war began, had been heart and soul with Mr. Churchill. But when he said the fine true thing it was like a faint air played on a pipe and lost on the wind at once. When Mr. Churchill said it, it was like an organ filling the church, and we all went out refreshed and resolute to do or die.

“A Little Touch of Harry in the Night”

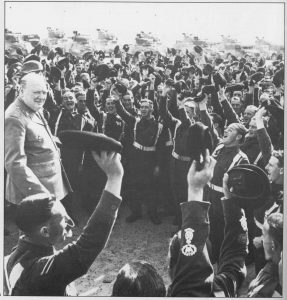

On the night before Agincourt, King Henry tours the English camp incognito, to gauge morale. The scene recalls Churchill’s 1899 account of the night before the Battle of Omdurman. Or Churchill’s visits with the troops in North Africa, before D-Day, and in France. But the closest analogy, I think, is in 1941. That was when President Roosevelt sent his confidant, Harry Hopkins, to Britain, to tell him if the UK was still worth backing.

Hopkins traveled up and down the land, devastated by the bomb damage he saw. Everywhere he went, he observed grit and determination, and faith in final victory. Hopkins had no doubts. In Glasgow, introduced by Churchill, he famously quoted the Book of Ruth: “Whither thou goest, I will go,” and he added, “even to the end.” Churchill wept.

We few…

Back in London, Lord Beaverbrook hosted Hopkins and the press at Claridge’s. “We wondered,” a Beaverbrook reporter said, “as our cars advanced cautiously through the blackout toward Claridge’s, what Hopkins would have to say. [He went round] the table, pulling up a chair alongside the editors and managers…and talking to them individually. He astonished us all, Right, Left and Centre, by his grasp of our own separate policies and problems. We went away content. And we were happy men all.”

We few, we happy few…

To many who heard or read his words—FDR, Beaverbrook, Robert Sherwood, even J. Edgar Hoover, who had FBI agents present—Hopkins reminded them of Henry V, touring the camp before Agincourt:

With cheerful semblance and sweet majesty,

That every wretch, pining and pale before,

Beholding him, plucks comfort from his looks…

Thawing cold fear, that mean and gentle all

Behold, as may unworthiness define,

A little touch of Harry in the night.

1415 and 1940

William F. Buckley Jr. said, “It was not the significance of victory, mighty and glorious though it was, that causes the name of Churchill to make the blood run a little faster. It is the roar that we hear when we pronounce his name…. The Battle Agincourt was long forgotten as a geopolitical event, but the words of Henry V, with Shakespeare to recall them, are imperishable in the mind, even as which side won the Battle of Gettysburg will dim from the memory of men and women who will never forget the words spoken about that battle by Abraham Lincoln.”

I think that might be true. It is the words, not the battles, that make the blood run faster in times to come. On the eve of Overlord in June 1944, General Ismay was reminded of Henry’s words at Agincourt:

He which hath no stomach to this fight,

Let him depart; his passport shall be made,

And crowns for convoy put into his purse.

Ismay heard one parachute commander say as he entered his aircraft:

And gentlemen in England now a-bed,

Shall think themselves accurs’d they were not here.

Of course that was a time, as I’ve said, when almost every Briton knew Shakespeare. And it was also a time, as Churchill added, “when it was equally good to live or die.”

Old Men Forget

In the same act, Henry tells his soldiers:

Old men forget: yet all shall be forgot,

But he’ll remember with advantages,

What feats he did that day….

In early 1943, writes Lewis Lehrman, “Churchill paraphrased those words to soldiers of the Eighth Army, who had defeated Rommel: ‘After the war, when a man is asked what he did, it will be quite sufficient for him to say, ‘I marched and fought with the Desert Army.’”

Churchill wrote in his History of the English-Speaking Peoples: When one of Henry’s officers “deplored the fact that they had ‘but one ten thousand of those men in England that do no work to-day,’ the King rebuked him and revived his spirits in a speech to which Shakespeare has given an immortal form:

If we are marked to die, we are enough

To do our country loss; and if to live,

The fewer men, the greater share of honour.

Compare that to May 28th again, or to Churchill’s greatest speech, 18 June 1940: “if the British Empire and its Commonwealth last for a thousand years, men will still say, ‘This was their finest hour.’”

“Collective Consciousness”

It was no coincidence, Jon Meacham writes, that

he tied the trials of the present to the collective consciousness of the world to come. Men will still say was a call to arms reminiscent of Henry V with the image of how the tale would be told from generation to generation. This story shall the good man teach his son [became] “Be brave now, and the future will cherish your memory and praise your name”—an impressive, if risky, means of leadership, for under stress not all of us are like Bedford and Exeter.

Churchill’s history records the King’s actual quoted words: “‘Wot you not,’ he said, ‘that the Lord with these few can overthrow the pride of the French?’ He and the few lay for the night.” On 20 August 1940, Churchill spoke of another small, outnumbered band, the RAF fighter pilots: “Never in the field of human conflict has so much been owed, by so many, to so few.”

Crispin’s Day

Remarkably, Churchill in his speeches or History never quoted from Henry V’s grand climacteric, the Crispin’s Day speech. In fact, writes Geoffrey Best, “he made far fewer historical and literary references than a more commonplace performer might have done. But the effect was to reproduce the congratulations addressed by Shakespeare’s hero to the Englishmen lucky enough to be with him at Agincourt.”

In his History, Churchill offers lines that are not Shakespeare’s: “The King himself, dismounted…and shortly after eleven o’clock on St. Crispin’s Day, October 25, he gave the order, ‘In the name of Almighty God and Avaunt Banner in the best time of the year, and Saint George this day be thine help.’ The archers kissed the soil in reconciliation to God, and, crying loudly, ‘Hurrah! Hurrah! Saint George and Merrie England!’”

Since he’d written those words already, who can say that Churchill didn’t remember them in his 19 May 1940 speech, “Be Ye Men of Valour?” There he said: “Our task is not only to win the battle but to win the War…for all that Britain is, and all that Britain means.” More modern language—but the sentiments are the same.

Constables of France

In the 1944 movie the Constable of France (Leo Genn) is not an empathetic figure. He is arrogant, imperturbable, impassive and phlegmatic—and supremely confident of victory. Then with the battle almost lost, he insists on returning to the fray and dying in combat.

In the 1944 movie the Constable of France (Leo Genn) is not an empathetic figure. He is arrogant, imperturbable, impassive and phlegmatic—and supremely confident of victory. Then with the battle almost lost, he insists on returning to the fray and dying in combat.

I think Churchill recalled this character when he wrote about Charles de Gaulle, during the fall of France in June 1940. Churchill tells us how, among the defeatist French, he came across this “impassive, imperturbable…tall, phlegmatic man.” On the last of those meetings before France surrendered, prompted I think by a recollection of the strongest French character in Henry V, he said of de Gaulle: “This is the Constable of France.” And so he was.

Acts of Union

Toward the end of the play, after wooing Katherine, Henry promises they will sire, out of Saint Denis and Saint George, celestial patrons, one of France and the other of England,

a boy, half French, half English,

who will go to Constantinople

and take the Grand Turk by the beard!

Marthe Bibesco, the Rumanian princess, in a good little 1950s book on Churchill, noticed this comparison: “And here we have,” she wrote, “in defiance of chronology, already predicted, the day after Agincourt, the Dardanelles expedition, which, in 1915 during the alliance between France and England will be so near to Churchill’s heart.”

She then cites words of the priest at the altar, Ye shall be two in the one flesh. “All those who know him,” she wrote, “would be prepared to swear that Churchill had this whole scene of Shakespeare’s in mind when he undertook that nuptial flight on 11 June 1940… The man who came that evening to ask for the hand of France in marriage offered her people dual nationality, with two passports, the right to vote in both countries, the pooling of the armed forces, in a word a true wedding!”

That’s a bit of a stretch—Churchill did make that offer, the Act of Union. But he little expected that it would be accepted, or have much effect, and it didn’t.

For Them Both, “It was Always England”

As Churchill goes on to write, Henry V’s French union was not to last. Churchill in old age likewise lamented that he had accomplished much, only to accomplish nothing in the end. And yet, what a self-description he offers us, writing of the King in 1938, not published until 1956. Henry V, he wrote:

was no feudal sovereign of the old type with a class interest which overrode social and territorial barriers. He was entirely national in his outlook: he was the first king to use the English language in his letters and his messages home from the front; his triumphs were gained by English troops; his policy was sustained by a Parliament that could claim to speak for the English people. For it was the union of the country [that gave Britain her] character and a destiny.

Is that not a description of Churchill himself? I think, if only subconsciously, he meant it to be.

His old friend Desmond Morton surmised that

for Churchill, it was always England…And thus Churchill was its man. He had never moved away from such a world…it had caught up with him from behind, a back slip in time. This was Henry V and all the great music of Shakespeare in the tribal soul….he saw himself mirrored in the pool of England. And England in him.

3 thoughts on ““The Pool of England”: How Henry V Inspired Churchill’s Words”

I’ve just been watching Branagh and Olivier’s renditions of Shakespeare’s Henry V speeches, trying to rouse myself for England’s Euro 2021 games! ;) In doing doing so, I was picking out similarities aplenty with Churchill’s greatest war speeches. When browsing the web for reports of the same, I should have known it would lead me straight back to you!

‘Only he acted from honesty and for the general good. His life was gentle, and the elements mixed so well in him that Nature might stand up and say to all the world, “This was a man.”’

–

Thanks sincerely for the very kind words. RML

Simply wonderful. I have always loved the Laurence Oliver version of Henry V. I grew up hearing stories about it and finally saw it with my father in the 1970’s at the Little Carnegie Movie Theater in NYC. My father first saw the film in Manila in 1945 (but not before arranging for a showing for General MacArthur).

–

Thanks kindly. RML

Brilliant

Comments are closed.