The Second Atlantic Charter? A Seventieth Anniversary

Excerpted from “Seventieth Anniversary of the ‘Second Atlantic Charter,’” written for the Hillsdale College Churchill Project. For the original article with endnotes and other images, click here. To subscribe to weekly articles from Hillsdale-Churchill, click here and scroll to bottom. Enter your email in the box “Stay in touch with us.” We never spam you and your identity remains a riddle wrapped in a mystery inside an enigma.

Q: What was it?

The Atlantic Charter was issued by President Roosevelt and Prime Minister Churchill in August 1941. “We had the idea,” Churchill later told Parliament, “to give all peoples, and especially the oppressed and conquered peoples, a simple, rough and ready wartime statement of the goal towards which the British Commonwealth and the United States mean to make their way, and thus make a way for others to march with them….”

A reader asks if the Charter had a second iteration:

In your review of Cita Stelzer’s Churchill’s American Network, you link Martin Gilbert’s 2005 lecture on Churchill and America. In it, Sir Martin said: “One of the documents which I’ve never seen reproduced…was the Declaration of Principles which Churchill and Eisenhower signed in the White House.” Was this, as he hinted, a second Atlantic Charter?

A: “Perhaps—perhaps not”

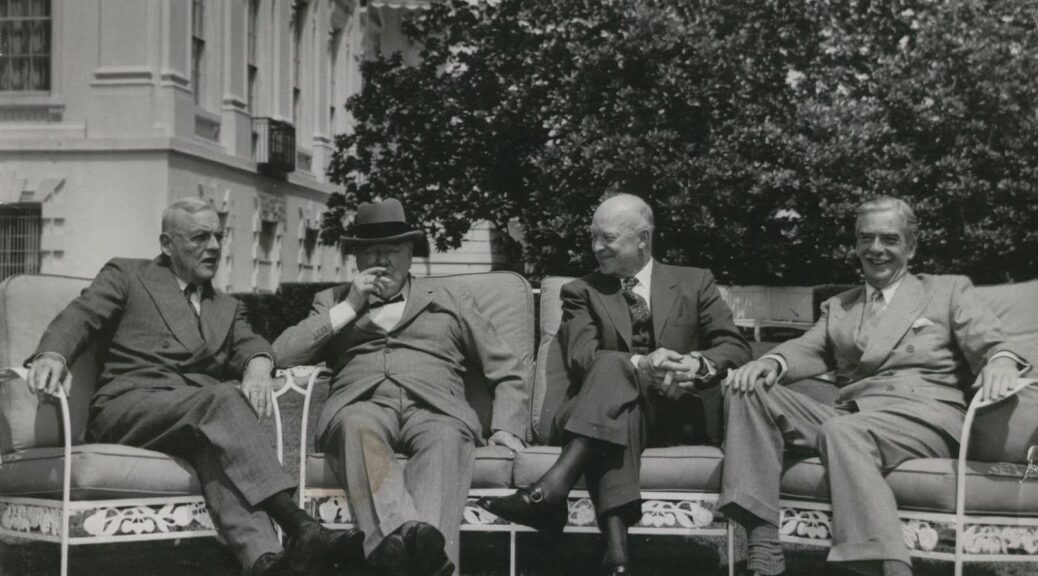

Sir Martin was quoting, actually paraphrasing, Churchill’s description of the charter he signed with Eisenhower in 1954. He correctly said it was never published. Finding it proved a challenge.

Sir Martin’s book Churchill and America references the Eisenhower Papers at Johns Hopkins University. The university library could not find it. They referred me to the Eisenhower Library, which did not reply. (Some libraries seem to have difficulties even answering queries about materials in their care.)

Repeated online searches eventually produced the text. Back in 2005, Sir Martin wished that President Bush and Prime Minister Blair publish the “Second Charter” as a gesture of solidarity during the Iraq war.

The Hillsdale College Churchill Project met Sir Martin’s wish that the “charter” be published, albeit on its seventieth anniversary. The wording certainly bears the imprint of Sir Winston.

Washington, 29 June 1954

As we terminate our conversations on subjects of mutual and world interest, we again declare that:

(1) In intimate comradeship, we will continue our united efforts to secure world peace based upon the principles of the Atlantic Charter, which we reaffirm.

(2) We, together and individually, continue to hold out the hand of friendship to any and all nations, which by solemn pledge and confirming deeds show themselves desirous of participating in a just and fair peace.

(3) We uphold the principle of self-government and will earnestly strive by every peaceful means to secure the independence of all countries whose peoples desire and are capable of sustaining an independent existence. We welcome the processes of development, where still needed, that lead toward that goal. As regards formerly sovereign states now in bondage, we will not be a party to any arrangement or treaty which would confirm or prolong their unwilling subordination. In the case of nations now divided against their will, we shall continue to seek to achieve unity through free elections supervised by the United Nations to insure they are conducted fairly.

*

(4) We believe that the cause of world peace would be advanced by general and drastic reduction under effective safeguards of world armaments of all classes and kinds. It will be our persevering resolve to promote conditions in which the prodigious nuclear forces now in human hands can be used to enrich and not to destroy mankind.

(5) We will continue our support of the United Nations and of existing international organizations that have been established in the spirit of the Charter for common protection and security. We urge the establishment and maintenance of such associations of appropriate nations as will best, in their respective regions, preserve the peace and the independence of the peoples living there. When desired by the peoples of the affected countries, we are ready to render appropriate and feasible assistance to such associations.

(6) We shall, with our friends, develop and maintain the spiritual, economic and military strength necessary to pursue these purposes effectively. In pursuit of this purpose we will seek every means of promoting the fuller and freer interchange among us of goods and services which will benefit all participants.

—Dwight D. Eisenhower, Winston S. Churchill

Self-government, self-determination

In the original Atlantic Charter, Churchill had been careful to distinguish self-government from self-determination. Britain and the U.S. agreed to “respect the right of all peoples to choose the form of government under which they will live.”

Churchill’s hand was again evident in the 1954 declaration, with its closely similar wording: “We uphold the principle of self-government…the independence of all countries whose peoples desire and are capable of sustaining an independent existence.” They welcomed “the processes of development, where still needed, that lead toward that goal.” (Italics mine.)

The British Empire was much diminished by 1954. But this wording preserved a certain flexibility for Britain over the colonies that remained. In the years which followed, under Churchill’s successors, colony after British colony became independent. Most evolved peaceably, and with far less strife than colonies of other empires. Today many are members of the useful, if sadly underutilized, Commonwealth of Nations.

“Rough-and-ready”

Churchill glossed over minor semantics in his report to Parliament. The statement, he said, was only “a declaration of our basic unity.” Angl0-American unity, he continued, was “the strongest hope that all mankind may survive in freedom and justice.

This was virtually the same meaning Churchill had attached to the 1941 Atlantic Charter: “A simple, rough-and-ready” statement by which Britain and America “mean to make their way.”

In retrospect

Was the 1954 Washington declaration a second Atlantic Charter? Probably not, writes Roosevelt-Churchill scholar Warren Kimball: “I’m a bit dubious about ordaining that statement, since it apparently attracted little attention and had no effect on history.”

Indeed, Churchill’s bright hopes for a “new charter” were quickly dashed. The Prime Minister was at sea, returning to England. There he dashed off a telegram to Soviet Foreign Minister Molotov, suggesting a high-level meeting with the Russians—absent Eisenhower.

Churchill informed Eisenhower, furious that he had not been consulted. ‘‘You did not let any grass grow under your feet,” he fired back. Back in London, the Cabinet was “even more indignant.” The Prime Minister had not consulted them, either.

Though the President later insisted he was “not vexed,” he wanted no Soviet summit. Privately, later, Eisenhower voiced the concern that “Winston would give away the store.”

Churchill’s initiative came to nothing. “I cherish hopes not illusions,” he replied. “And after all I am ‘an expendable’ and very ready to be one in so great a cause.”

In April 1955, convinced at last that he could not foster “a meeting at the summit,” Churchill resigned.

Three months later his successor and Eisenhower met with the Russians in Geneva.

Related reading

“Americans Will Always Do the Right Thing, After All Other Possibilities are Exhausted,” 2021.

“Researching the Atlantic Charter Conference, Argentia, Newfoundland, August 1941,” 2019.

“Bull in a China Shop (Dulles): Not Churchill’s Line,” 2022.

“Churchillian Phrases: ‘Special Relationship’ and ‘Iron Curtain,’” 2019.

“Cita Stelzer on the Angl0-American Special Relationship,” 2024.