“Americans will always do the right thing, after all other possibilities are exhausted”

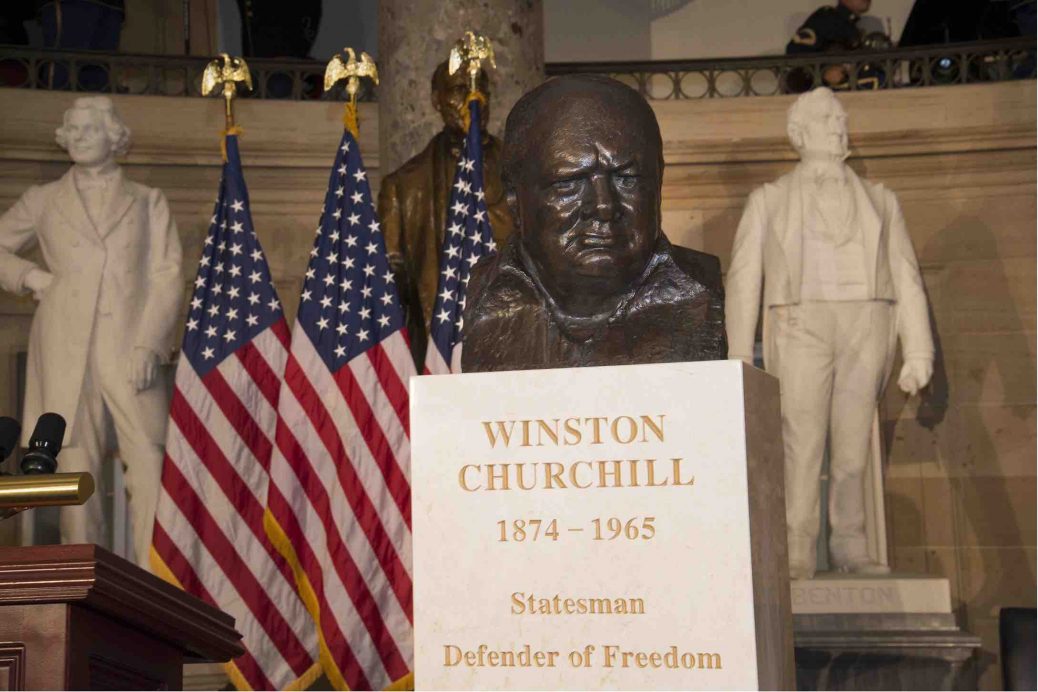

In 2011, Congress dedicated a new bust of Winston Churchill in the U.S. Capitol’s Statuary Hall. (Is it still there? These days you never know.)

Around the same time, Congress was engaged in the perennial mock debate about raising the debt ceiling. (The ceiling was rather lower then. If my ceiling had been raised as often in the last ten years, I’d be faced with zoning violations.)

In the debt ceiling debate Senator Angus King (I.- Me.) deployed, for the 3,408th time, a dubious Churchill aphorism: “Americans can always be trusted to do the right thing, once all other possibilities have been exhausted.”

Did Churchill ever say anything like that? The answer is: unproven. It is in my quotations book, Churchill By Himself, page 124, Chapter 8 (America), under the heading, “Characteristics of Americans.” But I waffled in the accompanying note:

Circa 1944. Unattributed and included tentatively. Certainly he would never have said it publicly; he was much too careful about slips like that. It cannot be found in any memoirs of his colleagues. I have let it stand as a likely remark, for he certainly had those sentiments from time to time.

Lack of provenance

This is one of the few quotes in my book for which I could not find solid attribution. I was been told that it came from Sir John “Jock” Colville‘s memoirs, but I couldn’t find it there. Nor did Sir John mention it in our conversations. If proven apocryphal it will go to my appendix of inaccurate quotations, entitled, “Red Herrings.” In the meantime, it sticks: former Congressman Paul Ryan used it awhile back (slightly inaccurately) in a speech at Claremont Institute.

It’s a great line—more appropriate right now than it was in 2011. Undoubtedly Churchill nursed those sentiments, though maybe not publicly. Here is another remark along those lines which we do know is genuine:

Their national psychology is such that the bigger the Idea the more wholeheartedly and obstinately do they throw themselves into making it a success. It is an admirable characteristic, providing the Idea is good. —The Second World War, vol. V, Closing the Ring (London: Cassell, 1952), 494.

Reader comments

The post above is reprised from its first publication ten years ago. At the time it drew these comments by readers:

Micah: “Quote Investigator offers what seems to be a pretty credible genealogy of this quote. They attribute it to Abba Eban (1915-2002), a longtime Israeli Foreign Minister.”

There’s no reason to doubt Q.I. Don’t you wish we could find the exact moment where some gag becomes Churchillian Drift? It is now broadly accepted that Nancy Astor told Churchill’s close friend F.E. Smith that if she were married to Smith, she’d put poison in his coffee. F.E.—a great wag, and faster off the cuff than Churchill—replied that if he were married to her, he’d drink it. Wouldn’t it be fun to know precisely when some villain drifted that crack from the forgotten F.E. Smith to the legendary Churchill?

Richard Munro: “I have often heard it quoted, even by reputable historians. You are right to be cautious. In any case it is not really very complimentary to Americans. I always thought it was unChurchill-like in its slight anti-Americanism. I think it will be found to belong to someone else ultimately.”

Many would not see this remark as anti-American, but as a plain expression by a friend—and after all, it has often been true. As has been said, “A friend is someone who knows all about you, but likes you.”

Recently a prominent historian said Churchill “could never quite make up his mind whether America was Britain’s friend or Britain’s enemy.” Are we sure about when exactly WSC had that trouble?

“Yes there were times, I think you knew….”

Churchill was appalled over Woodrow Wilson’s naiveté at Versailles. He railed over U.S. insistence that Britain repay every debt from the First World War, which had cost Britain the flower of a generation. He criticized the U.S. system of set four-year elections—many still do today. WSC chafed over America staying out of World War II until Japan forced her hand. He argued over when and where to invade Hitler’s Europe. FDR’s apparent “tilt” toward Stalin at Teheran depressed him. But from the time he set foot in America, Churchill never deviated from the belief in the centrality of Anglo-American fraternity. Never did he lose hope in “the Great Republic.”

The “Special Relationship,” born in 1940, had been nurtured by his American mentor Bourke Cockran four decades earlier. To understand Churchill is to appreciate his belief in the primacy of U.S. friendship, which never wavered, however often he disagreed with U.S. policy. That was established on his first visit to America in 1895, when he wrote his brother: “This is a very great country, my dear Jack.”