Cita Stelzer on the Anglo-American Special Relationship

Excerpted from “Cita Stelzer Examines Churchill’s Hold on Americans—and Theirs on Him,” written for the Hillsdale College Churchill Project. For the original article, click here. To subscribe to weekly articles from Hillsdale-Churchill, click here, scroll to bottom, and enter your email in the box “Stay in touch with us.” We never spam you and your identity remains a riddle wrapped in a mystery inside an enigma.

*****

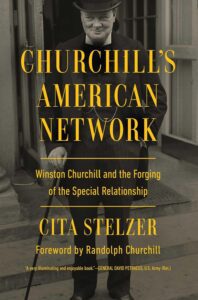

Cita Stelzer. Churchill’s American Network: Winston Churchill and the Forging of the Special Relationship. New York: Pegasus Books, 2024. 236 pages, $29.95, Amazon $26, Kindle $19.99.

Cita Stelzer. Churchill’s American Network: Winston Churchill and the Forging of the Special Relationship. New York: Pegasus Books, 2024. 236 pages, $29.95, Amazon $26, Kindle $19.99.

Cita Stelzer…

…offers a lively and readable account of Winston Churchill’s hold on important Americans—and theirs on him. Her book nicely complements Sir Martin Gilbert’s Churchill and America (2005). Add Brad Tolppanen’s Churchill in North America 1929 (2014), and you have an excellent triptych on the Anglo-American Special Relationship.

Gilbert’s book was chronological and complete; Tolpannen concentrated on a single year. Stelzer splits the difference. She begins with Churchill’s first U.S. visit in 1895 and ends with the outbreak of the Second World War. Churchill’s long skein of American contacts served him well, and she could easily write a sequel covering the war years and beyond.

Nearly two-thirds of Churchill’s American Network is devoted to his nationwide tours of 1929 and 1931. Churchill’s American Network shows how WSC honed his U.S. contacts, begun in the First World War, that proved so indispensable in the Second.

Early on

On his first U.S. lecture tour in 1900-01, Stelzer observes, young Winston was viewed with some diffidence. Americans tended to sympathize with the Boers, Britain’s enemy in South Africa. Churchill disarmed them by paying tribute to Boer valor—and, in places like Boston, that of his Irish compatriots. Stelzer quotes Manfred Weidhorn on how Churchill, like U.S. Grant, successfully relied on “personal observation” in his war reporting (71).

As First Lord of the Admiralty in 1915, Churchill met steel magnate Charles M. Schwab, whose Bethlehem Steel was supplying guns to the Allies and “c.k.d.” (crated knocked down) submarines to the Royal Navy. Thus, the First Lord became aware of the “awesome productive capacity” of American industry. They remained close, and Schwab would supply the “Churchill Troupe’s” private railcar for their North American tour in 1929.

Return to “dry” America

By the late Twenties, Churchill’s chief American contact was Bernard Baruch, like Schwab another Great War acquaintance. Stelzer is our guide as the towering financier eases into the heart of the story, 1929-32. From Baruch, WSC learns “the relationship of finance and government and how private sector determined deployment of the nation’s resources” (119).

Two years later, back now for a lecture tour, Churchill assured audiences that “America is not going to crash.” But he couldn’t get over Prohibition, and denounced it in Collier’s. Cita Stelzer ferrets out a poignant quote from that article about the evils of excessive government regulation. Prohibition then, the dominant Administrative State now—Churchill’s view is still worth our attention:

[It is] the most amazing exhibition alike of the arrogance and of the impotence of a majority that the history of representative institutions can show. The extreme self-assertion which leads an individual to impose his likes and dislikes upon others…on a gigantic scale a spectacle at once comic and pathetic…. No folly is more costly than the folly of intolerant idealism (81).

Forging “special relationships”

If Churchill coined the term “Special Relationship” for Anglo-American association, he derived it from the contacts he himself forged. Yet not even he, Stelzer observes, “realized how important” the people he met would become.

There were, for example, future War Secretary Henry Stimson, Ambassador to Britain Andrew Mellon, and Navy Secretary Charles Francis Adams III (110). There were certain key publishers, who didn’t always agree with him, but liked him. From William Randolph Hearst he learned “the variety and popularity of U.S. magazines accessing public opinion” (101).

Another vital publisher was Chicago’s Robert McCormick, who agreed with him even less than Hearst, but liked him equally. When the war began, Anglophobe Senator Tom Connolly questioned whether Churchill would keep his promise never to surrender the Royal Navy. McCormick told him: “Senator, I have known Winston Churchill for twenty-five years. A more thoroughly honorable man never lived. He would not have made that promise if he had not intended to keep it” (204).

American grandees were impressed by Churchill’s collegial attitude toward political opposites like McCormick. After his triumphant address to Congress following Pearl Harbor, he warmly shook hands with Democrat isolationist Senator Burton K. Wheeler. Later Churchill said, “I liked him. He is a fighting man…. I respect and admire fighting men even if they are against me” (209).

“Volume diplomacy”

To nurture his U.S. contacts Churchill employed a kind of “volume diplomacy.” He inscribed and sent successive volumes of his life of Marlborough to America’s haute noblesse. Baruch, Schwab, McCormick Hearst, Senator Joe Robinson, and B&O Railroad head Daniel Willard all received copies. Another recipient was insurance tycoon Donald McLennan, who in 1942 extended war damage insurance to endangered companies other insurers wouldn’t touch.

On Churchill’s gift list was Democrat powerhouse and former presidential candidate William McAdoo. In 1929, Baruch had told McAdoo of WSC’s forthcoming visit. McAdoo wrote Churchill: “[G]ive me…some indication of what you would like to do while here….Do you care for any form of public entertainment?” WSC replied, “Do not desire public entertainment but hope to dine with you privately” (62).

Marlborough also went to banker William Henry Crocker, whose Burlingame, California mansion included “a splendid swimming pool.” Crocker had introduced Churchill to several West Coast titans (83). Among these were Cal Tech President and physicist Robert A. Millikan, USC President Rufus B. von KleinSmid, and actor Douglas Fairbanks Jr. All of them, Stelzer writes, would later support American entry into the Second World War (100). A dose of Winston Churchill hadn’t hurt.

A positive vice

To the consistent horror of his wife, Churchill was an incessant (mostly losing) gambler—casinos and the stock market. His habit, Cita Stelzer writes, “did nothing to improve his reputation among the straitlaced…including Schwab’s associate, “the puritanical Andrew Carnegie” (57). She quotes financial historian David Lough: “I have never encountered risk-taking on Churchill’s scale during my career of advising people about their finances” (125).

But Stelzer sees a saving grace, in that WSC’s addiction was a net gain for him and his readers. “It forced him to rely on his pen, producing forty-three book-length works in seventy-two volumes” Actually it was fifty-one books in eighty volumes—but as Stelzer writes, this was “a gift to the world.” (126)

To that she adds some 400 periodical articles between the World Wars, a dramatic output. Indeed Churchill never stopped writing—and earning. Confined to a New York hospital after being knocked down and nearly killed by a car in 1932, he dictated the story of his accident at a dollar a word.

At the same time, the author continues, he was “in treaty” for twelve Collier’s articles and six for The Strand. Meanwhile, he was telegraphing publisher George Harrap that he had “no serious work between me and [Marlborough] at the present time.” (138)

With Americans, Churchill seemed more cautious about risk-taking. He met Averell Harriman between casino visits in 1927, warning him against investing in Soviet manganese mines. Later he claimed he had saved Harriman millions. Whether Harriman took his advice is unclear, Stelzer writes, but here was another link to “his American chain of relationships that would stand him in good stead for decades” (64). In an adjacent sidebar—one of many on people and events—the author details Harriman’s wartime diplomacy with Churchill and Stalin.

Churchill on Americans

On his very first visit to the U.S., Churchill had written his mother: “What an extraordinary people the Americans are! Their hospitality is a revelation to me and they make you feel at home and at ease in a way that I have never before experienced.” To his brother he simply remarked: “This is a very great country, my dear Jack.”

Cita Stelzer shows that he never found reason to alter that impression. Thirty-five years later he wrote of “gusts of friendliness…expansive gestures…hospitality and every form of kindness… [Americans] are less indurated by disappointment; they have more hopes and more illusions.” This, he observed, meshed well with British “traditional reserve and frigidity….chary of allowing the feeling of friendliness to take root quickly…. It is in the combination of these complementary virtues and resources that the brightest promise of the future dwells” (119).

Again Manfred Weidhorn, “a keen student of Churchill’s attitudes toward America,” is quoted: The United States in Churchill’s view was “a great experiment, a trail blazer, in so many ways the leading nation of the world and the carrier of the hopes of mankind” (193).

Americans on Churchill

A few minor errors of fact do not detract from a good read, full of insight tempered by honesty. For instance, Cita Stelzer doesn’t hide Churchill’s willingness to take advantage of good-natured American hospitality, sometimes with unabashed pushiness. In 1929 she has him writing Hearst to find out whether banker William Crocker or aircraft and oil baron George Armsby “would like to take care of me in San Francisco” (76).

Yet she notes that Churchill’s outgoing character, his fraternal love of his mother’s land, soon disabused his hosts of base impressions. The Anglophile journalist Frederick Wile was not the first American to go out on a limb (albeit with a nickname WSC detested): “Dynamic, brilliant, resourceful and lion-hearted, ‘Winnie’s’ path, his admirers are persuaded, one day will lead him to the premiership” (110).

It would—but not quite in the way Wile expected.

In 1941, a few months after the whole world had seen what his indomitable character had made him, even Americans who had been dismissive were giving Churchill another look. That was when one of his U.S. acquaintances, Henry Luce, named him Time’s “Man of the Year.”

“Churchill cannot reasonably claim to have recruited Henry Luce to his network,” Stelzer writes. “But he can reasonably claim to have attracted Luce to his side…. Luce needed Churchill to make the case for intervention, Churchill needed Luce to make his arguments available to millions, Roosevelt needed both” (209). Mutual need featured hugely in the “Special Relationship.” It still should today.

On America and Americans

From Sir Martin Gilbert’s remarks on Churchill and America, Chartwell Booksellers, New York, 11 October 2005.

In the beginning….

He came here first in 1895, and he was quite amazed by New York, which was the one city he visited—he was on his way to Cuba to watch the Spaniards grappling with the Cuban insurrectionists. He wrote to his young brother:

Picture to yourself the American people as a great lusty youth who treads on all your sensibilities, perpetrates every possible horror of ill manners, whom neither age not just tradition inspire with reverence, but who moves about his affairs with a good-hearted freshness which may well be the envy of older nations of the earth.

Toward the end….

One of the documents which I’ve never seen reproduced in any history book or collection of documents was the Declaration of Principles which Churchill and Eisenhower signed in the White House on 27 June 1954. He summarized it in a speech to Parliament:

Britain and the United States assert their sympathy for and loyalty to all those still in bondage, proclaim their desire to reduce armaments, and to turn nuclear power into peaceful channels, confirm their support of the United Nations, and all organizations designed to promote peace in the world; and proclaim their destination, to develop and maintain the spiritual, economic and military strength necessary to pursue their purposes effectively based on their mutual comradeship.

In 1955 he summoned his cabinet together for a final chat. And he said to them, “there are two things which matter. One is to remember that man is spirit. And the other thing is: Never be separated from the Americans.”

Related reading

“Origins of Churchill Phrases: ‘Special Relationship’ and ‘Iron Curtain,'” 2019.

“Churchill Quotations: The Best Telegram He Ever Sent,” 2023.

“Americans Will Always Do the Right Thing, After All Other Possibilities are Exhausted,” 2021

“Dewey, Hoover, Churchill, and Grand Strategy, 1950-53,” 2018.