“The Wilderness Years” with Robert Hardy: Original Review

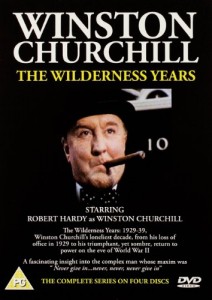

“Churchill: The Wilderness Years”

The Hillsdale College Churchill Project has just republished “Scaling Everest,” Robert Hardy’s recollections of playing the Wilderness Years Churchill. They are from 1987, his speech to one of our Churchill Tours, at the Reform Club, London. We are grateful to his executors, Justine Hardy and Neil Nisbet-Robertson for permission to reprint. For Part 1, click here.

I thought the occasion appropriate to republish my original review of the “Wilderness Years” from 1981, some years before we met. I thought at the time I had “laid an egg”—in Churchill’s phraseology, not RH’s. (In his business, as he explains, laying an egg means something different.) Now I am not so sure. I hope, to use Robert’s terms, that it was not a noxious egg.

Boston, 1981

Well, it was a great show, folks. And, inasmuch as any good material about Churchill is a plus, we welcomed and enjoyed it. We are beholden to WGBH in Boston, which most kindly mentioned Martin Gilbert’s accompanying Wilderness Years book.

Let us dismiss Lord Boothby’s complaint that this Winston is “a grumpy, vindictive old man [who] shouts all the way through.” Robert Hardy captures the Churchill of the Thirties. He was politically frustrated, ineffective as a father, worried about Germany. Simultaneously, he enjoyed of his most productive decades as a writer and historian. Perhaps it would be remarkable of anyone else. Churchill was engaged in multiple literary projects, any one of which would fully occupy a normal person. Simultaneously he turned Chartwell into a paradise and was a force, however spurned, in politics. His only wilderness was the one observers assigned to him.

And this may be the weakness of the production. It is hard to provide much TV action around the writing of Marlborough, though we’d have enjoyed seeing the great Duke’s battlefields. There is no drama to painting a canvas or building a brick wall.

We are given instead what plays well: politics, love, scandal, hate. Here enter several exaggerations. Adolf Hitler (Gunter Meisner), on the eve of power, glares through a restaurant window at the Churchill he refuses to meet. Of course the real Hitler did no such thing. Neville Chamberlain (Eric Porter), and his toady Sir Horace Wilson (Clive Swift, “Richard Bucket” in “Keeping Up Appearances”) still think well of Hitler after March 1939. That is unfair to Chamberlain, who knew by then what he was up against. The desert scene with William Randolph Hearst (Stephen Elliott) and Marion Davies (Merrie Lynn Ross) never happened.

On the money historically

On the other hand, “The Wilderness Years” brings out important aspects of the story. Randolph (Nigel Havers) couldn’t be more like Randolph. The risks run by Ralph Wigram (Paul Freeman), Desmond Morton (Moray Watson) and Wing Commander Tor Anderson (David Quilter), in bringing Churchill news of German rearmament, are rightly emphasized. How often Stanley Baldwin (Peter Barkworth) played Churchill foul in the 1930s! (And how often WSC forgave him.) “The Wilderness Years” relays all this well.

In general the casting was superb. British television draws on an army of brilliant actors, and can always find a near-clone of anybody. I thought Baldwin was too pixieish, Ramsay MacDonald (Robert James) too mousy, Hitler a caricature. But Frederick Lindemann, “The Prof” (David Swift), Brendan Bracken (Tim Pigott-Smith), and Beaverbrook (Stratford Johns) were perfect. So was Lord Derby (Frank Middlemass, transformed from the kindly head master in “To Serve Them All My Days”). Neville Chamberlain couldn’t have been closer to life. Samuel Hoare (Edward Woodward) comes across as the evil force he really was.

Most of the women—WSC’s vivacious sister-in-law “Goonie” (Jennifer Hilary), noisy Nancy Astor (Marcella Markham) and Sarah Churchill (Chloe Salaman)— were well played. But there was one exception. Clementine Churchill (Sian Phillips) was simply awful. A friend who remembers Phillips for her role in the Roman drama “I Claudius” says: “I keep seeing her sipping wine and wearing a toga.” Was she typecast? Viewers must be the judge.

Flaws and edits

Phillips was not the “Clemmie” we know through Martin Gilbert’s and Mary Soames’s biographies. Instead we see a pretentious, unhappy aristocrat. Less a pillar of strength than a flitting mayfly, she is always ready to run off with some handsome adventurer. All the more curious (for Phillips said she researched the role), Clemmie is at sea literally and figuratively. The scene in which she returns from a South Seas voyage with an unnamed swashbuckler (in life, Terence Phillip) would thrill the National Enquirer, however unsubstantial its implications. Phillips could have saved the scene by reciting Clementine’s own words. “Do not be vexed with your vagabond cat. She has gone off toward the jungle with her tail in the air, but she will return presently to her basket and curl down comfortably.”

We could have done without the bowdlerization of Churchill’s great speeches. Robert Hardy had his part down perfectly. (One soon forgets the lovable vet Siegfried Farnon in “All Creatures Great and Small.”) But almost every great speech, though beautifully delivered, was mercilessly cut to ribbons by the editors. The hatchet job on Churchill’s greatest prewar speech (“I have watched this famous Island…”) is unforgivable.

Still it is a great yarn. What historical character other than Churchill could excite a latter-day audience by reprising his life’s lowest ebb? As ever, Winston Churchill stands alone. I hope that the fine reception of “The Wilderness Years” has been sufficient to encourage further dramatizations of equally important periods—particularly the Admiralty sojourn of 1911-15, and of course, 1940. We’ll be waiting for it.