Churchill Myth and Reality: Antwerp. Shocking Folly?

Churchill’s role in the defense of Antwerp, in October 1914, has been called one of his “characteristically piratical” adventures. An eminent historian described it as “a shocking folly by a minister who abused his powers and betrayed his responsibilities. It is astonishing that [his] cabinet colleagues so readily forgave him for a lapse of judgment that would have destroyed most men’s careers.”1

As the Germans closed in around Antwerp, Max Hastings writes, Churchill “assembled a hotchpotch of Royal Marines and surplus naval personnel… his own private army.” Then he “abandoned his post at the Admiralty.” Then he “had himself appointed Britain’s plenipotentiary to the beleaguered fortress.”2

The Royal Naval Division

Before the war, Churchill had opposed conscription (“the draft”). He soon changed his mind. What contribution could the Admiralty make? Churchill wondered. His eye fell upon a surplus of 20-30,000 Royal Navy reservists not needed aboard ships.

Churchill organized them into one marine and two naval brigades for operations on land.3 With the addition of the two naval brigades—and with cabinet approval—the Royal Naval Division was founded on August 16th. “Its men regarded Churchill as their patron,” Martin Gilbert wrote. “Later, in action, when things went well they called themselves ‘Churchill’s Pets.’ When things went badly they were known as ‘Churchill’s Innocent Victims.’”4

The Secretary of State for War, Lord Kitchener, approved setting up the Division. Political associates besieged Churchill to make places for their relatives. The Conservative leader Andrew Bonar Law wrote on behalf of his two nephews; ironically, Bonar Law and others like him were later Churchill’s leading critics.

The RND first saw action at Ostend, where two battalions of marines landed temporarily to secure the city during the Allied retreat. It is true, as later critics said, that naval personnel were not ideal for shore operations. But Kitchener and Churchill never visualized RND personnel as first-line troops. They thought of them as temporary expedients when regular troops were unavailable.

Decision to Defend Antwerp

Churchill’s “piratical” decision to defend Antwerp was actually that of the cabinet. As Churchill had predicted,5 the Germans had made rapid advances in the opening weeks of the war. They secured Brussels, Belgium’s capital, and by the end of September 1914 were threatening Antwerp, one of its last lines of defense. The Belgians informed their allies that Antwerp would have to surrender by 3 October. The British said: not so fast.

Lord Kitchener—backed by the cabinet—emphasized the importance of holding Antwerp as long as possible. This would enable the transfer of troops and equipment to safer ports farther south on the Channel coast. Antwerp posed a barrier to the enemy’s advance. Kitchener feared that if the Germans reached Calais, they might be able to launch an invasion of Britain. Churchill supported him, and one of the Admiralty’s prime duties was to keep the Channel ports open. The cabinet agreed that “the more troops [the Germans] would be forced to divert to the siege…the more coastline would remain in Allied hands.”6

Foreign Minister Lord Grey cited a moral imperative to aid “brave little Belgium.” He told the Belgians that a “further effort” should be made at Antwerp. He promised that Britain would dispatch troops.

Send in the Marines

Pending their arrival, Kitchener, at Churchill’s suggestion, decided to send the RND marine brigade, which was already in Dunkirk, returning from Ostend. Meanwhile the French government, in emergency session at Bordeaux, promised to send two territorial (reserve) divisions, complete with artillery and cavalry, “with the shortest delay possible.” The French also promised to launch an offensive toward Lille that would press the Germans from another direction. Some questioned the effectiveness of territorials in a fight for the city—yet the Germans were using the same type of troops in more substantial numbers (60,000).7

Kitchener wished to deploy regular army troops at Antwerp, but he needed information on the situation, which appeared vague at best. On October 2nd he noticed that Churchill was en route to Dunkirk to evaluate the marine brigade and consult with the British commander, Sir John French. Kitchener stopped Churchill’s train and returned it to London, where they met, along with Lord Grey and the First Sea Lord, Prince Louis of Battenberg. They decided to re-route Churchill to Antwerp, where he might report the exact situation. Churchill did not, therefore, “have himself appointed.”

Nor did Churchill “abandon his post.” He left Battenberg in charge at the Admiralty, under direction of Prime Minister H.H. Asquith, before he set off. Asquith and Kitchener anxiously awaited Churchill’s report, Asquith with gusto: “I don’t know how fluent he is in French, but if he was able to do himself justice in a foreign tongue, the Belges will have listened to a discourse the like of which they have never heard before.”8

“Churchill’s Private Army”

Churchill did not prefer the “hotchpotch collections of naval personnel,” including recruits, that showed up at Antwerp. Kitchener had planned to send a “substantial” Antwerp relief force under the command of Sir Henry Rawlinson to take over the defense. They could not be sent immediately, so Kitchener accepted Churchill’s suggestion of the marine brigade, supplemented by two naval brigades from the Royal Naval Division: Churchill’s so-called “private army.”

Prime Minister Asquith knew the truth. He had explained to the King that in the present emergency, there were no other troops available to support Antwerp’s defense. Asquith also knew that

on October 4, in his telegram to Kitchener, Churchill had explicitly requested the Naval Brigades to be sent, “minus recruits“; all subsequent arrangements for the despatch of the brigades had been made at the Admiralty by Prince Louis…. The recruits could easily have been held back had Prince Louis or Asquith desired. When, on October 5, Churchill found that the brigades had come with their recruits, and were about to be exposed to the full weight of a German assault, he had given immediate orders for them to take up a less exposed, defensive position. (Emphasis added.)9

These facts were not made public at the time. Ever since, there have been venomous accounts of Churchill’s actions.

“Mon dieu! La Trinité?”

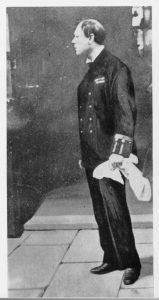

Churchill arrived in Antwerp at mid-day on 3 October, wearing the uniform of an Elder Brother of Trinity House (Britain’s lighthouse service had honored him with this title in 1911). It was distinguished by a naval cap with badge and pea jacket. A Belgian officer asked what this get-up signified. Churchill replied, in his lame French: “Moi, je suis un frère aîné de la Trinité.” The dumbfounded Belgian exclaimed: “Mon Dieu! La Trinité?”10 He had understood Churchill to have proclaimed himself divine. The story would not be lost on critics who believed Churchill thought of himself in precisely that way.

An eye-witness described the scene as Churchill drove out to inspect the defenses:

It was a chilly day and he [had changed into] a long black overcoat with broad astrakhan collar and his usual black top hat, and swung his silver-topped walking stick. In his customary manner, he completely ignored the enemy fire from howitzers, rifles and machine guns and astonished the Belgian troops by taking complete charge of the situation, criticizing the siting of guns and trenches and emphasizing his points by waving his stick or thumping the ground with it.

He then climbed back into his car, waiting impatiently to be driven to the next section of the front line. Later, when the reinforcing Royal Marines arrived and were settled in, Winston came along to inspect them, dressed suitably for this more maritime occasion. He was “enveloped in a cloak, and on his head wore a yachtsman’s cap,” observed an accompanying journalist. “He was tranquilly smoking a large cigar and looking at the progress of the battle under a rain of shrapnel which I can only call fearful.’”11

The Outcome

By 5 October neither the promised French or British troops, nor the designated commander, General Rawlinson, had shown up. There was no on-scene leader, save Churchill.

In what seemed to him an emergency, Churchill offered to resign from the Admiralty to conduct the defense of the city. Asquith saw this uncharitably. The Prime Minister, who should have had Churchill’s back, remarked privately: “Winston is an ex-Lieutenant of Hussars, and would if his proposal had been accepted, have been in command of two distinguished Major Generals, not to mention Brigadiers, Colonels etc: while the Navy were only contributing its little brigades.”12

Lieutenant of Hussars he may have been. But among Asquith’s cabinet, Churchill had had more first-line military experience than anyone else, and had thought more about the business than his colleagues. Asquith didn’t bother to add, Martin Gilbert noted, “that those ‘little brigades,’ whose role he minimized, were in fact the only British forces at that moment available for immediate despatch to Antwerp, and that one of them, the marine brigade, constituted at the time the only British force engaged in the city’s defense.”13

Betrayal and Incompetence

To Churchill’s face, Asquith was charm itself. He needed him. When would he return? The answer proved to be: when Rawlinson got to Antwerp. The General finally showed up late on the 6th, having taken three times as long to arrive as Churchill had. Ironically, Rawlinson left Antwerp shortly after Churchill, deciding that further defense was futile.

In the absence of promised French or British reinforcements the commanding officer, Major-General Archibald Paris, had only “hotchpotch” British defenders. Churchill had ordered him to continue the defense for as long as possible and to be ready to cross to the west bank rather than participate in a surrender. General Paris conducted a gallant defense for three more days. Antwerp formally surrendered on 10 October.14

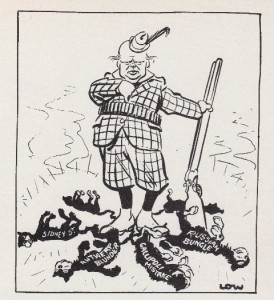

The Reaction

The First Lord returned home believing he had slowed the German advance and prevented the enemy from turning the Allied flank. Instead of a welcome, he faced an uproar. Typical was the editorial by H.A. Gwynne of the Morning Post, ironically a newspaper that had once lauded his contributions as a war correspondent. The government, Gwynne wrote, needed

to keep a tight hand upon their impulsive colleague [and] see that no more mischief of the sort is done…. The attempt to relieve Antwerp by a small force of Marines and Naval Volunteers was a costly blunder, for which Mr. W. Churchill [is] responsible…. It is not right or proper that Mr. Churchill should use his position as Civil Lord to press his tactical and strategical fancies upon unwilling experts….”15

The Reality

But facts are stubborn things, and facts say otherwise. In no case did Churchill advance “strategical fancies upon unwilling experts.” In no case did he deploy troops without approval of the cabinet and the responsible minister, Lord Kitchener. The object was not the relief of Antwerp. The object was to delay and harass the enemy, forestalling a greater disaster.

The Royal Naval Division brigades were closest and easiest to transport, and acquitted themselves well, with only fifty-seven deaths out of 8000. Kitchener and Rawlinson (in a foretaste of Gallipoli) had dawdled and failed to deliver. The French (in a foretaste of 1940) had failed utterly. Asquith, Kitchener and the Admiralty sent only recruits. Churchill had recommended against them.

King Albert Weighs In

As a government minister, Churchill could not reply to all this. He received no public defense from Asquith or Kitchener. Belatedly, the King of the Belgians revealed the truth. In a letter to General Paris in March 1918, which he later dictated as a memorandum, King Albert wrote:

You are wrong in considering the Royal Naval Division Expedition as a forlorn hope. In my opinion it rendered great service to us and those who deprecate it simply do not understand the history of the War in its early days. Only one man of all your people had the prevision of what the loss of Antwerp would entail and that man was Mr. Churchill….

Delaying an enemy is often of far greater service than the defeat of the enemy, and in the case of Antwerp the delay the Royal Naval Division caused to the enemy was of inestimable service to us. These three days allowed the French and British Armies to move North West. Otherwise our whole army might have been captured and the Northern French Ports secured by the enemy.

Moreover, the advent of the Royal Naval Division inspired our troops, and owing to your arrival, and holding out for three days, great quantities of supplies were enabled to be destroyed. You kept a large army employed, and I repeat the Royal Naval Division rendered a service we shall never forget.15

This article is Chapter 11 in…

…my new book, Winston Churchill, Myth and Reality: What He Actually Did and Said, available at a $15 discount from the Hillsdale College Bookstore. Also available in print and Kindle editions from Amazon.

Endnotes

1. Max Hastings, Catastrophe 1914: Europe Goes to War (New York: Random House, 2013, Vintage Books paperback 2014), 446–55.

2. Ibid.

3. “The British Army 1914–1918,” www.1914–1918. net/63div.htm, accessed 14 March 2016.

4. Martin Gilbert, Winston S. Churchill, vol. 3, The Challenge of War 1914-1916 (Hillsdale Mich.: Hillsdale College Press, 2008), 48.

5. See Winston S. Churchill, “Military Aspects of the Continental Problem,” in The World Crisis 1911–1914 (London: Thornton Butterworth, 1923), 60–64.

6. Gilbert, Challenge of War, 104.

7. Ibid.

8. H.H. Asquith, Memories and Reflections, two vols. (Boston: Little Brown, 1928) II 41.

9. Gilbert, Challenge of War, 131.

10. Richard M. Langworth, ed., Churchill by Himself (New York: Public Affairs, 2008), 524.

11. Richard Hough, Winston and Clementine (London: Bantam, 1990), 288.

12. Henry Pelling, Winston Churchill, 1974. Revised and extended softbound edition. (Ware, Herts.: Wordsworth Editions, 1999), 184.

13. Gilbert, Challenge of War, 113–14.

14. J.E. Edmonds, Military Operations France and Belgium, 1914: Mons, the Retreat to the Seine, the Marne and the Aisne August–October 1914. History of the Great War Based on Official Documents by direction of the Historical Section of the Committee of Imperial Defence I, 2nd ed. (London: Macmillan, 1926), 46–48.

15. H.A. Gwynne, “The Antwerp Blunder,” Morning Post, London, 13 October 1914, in Gilbert, Challenge of War, 125–26.

16. Ibid., 125.