Hitler’s Sputtering Austrian Anschluss: Opportunity Missed?

Excerpted from “Hitler’s ‘Tet Offensive’: Churchill and the Austrian Anschluss, 1938″ for the Hillsdale College Churchill Project. If you wish to read the whole thing full-strength, with more illustrations and endnotes, click here.

Better yet, join 60,000 readers of Hillsdale essays by the world’s best Churchill historians by subscribing. You will receive regular notices (“Weekly Winstons”) of new articles as published. Simply visit https://winstonchurchill.

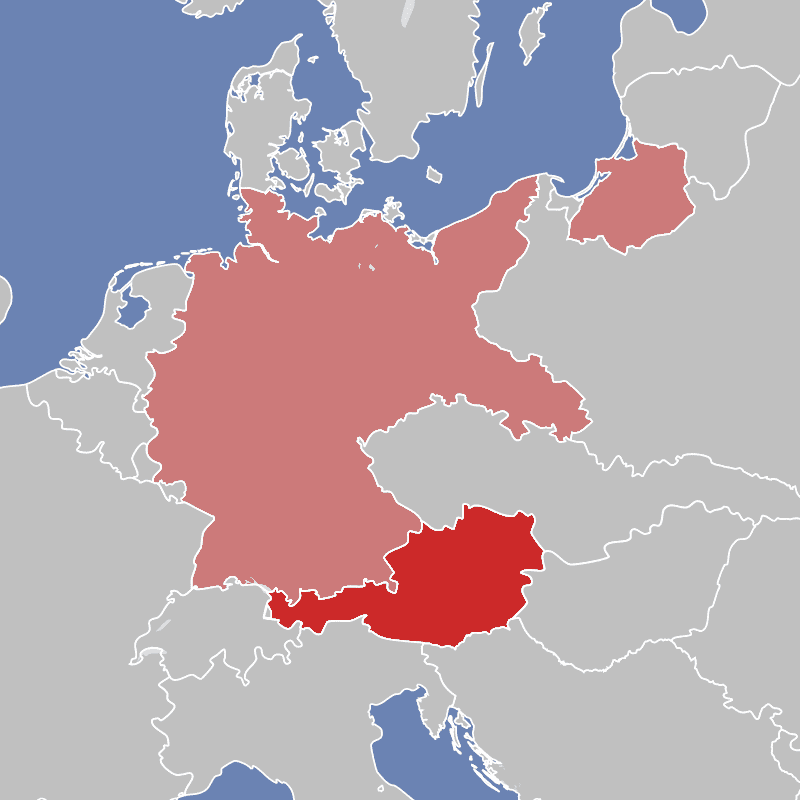

Austria and the Reich

“Don’t believe that anyone in the world will hinder me in my decisions! Italy? I am quite clear with Mussolini…. England? England will not lift a finger for Austria. —Adolf Hitler to Kurt von Schuschnigg, 12 February 1938, a month before Anschluss.

* * *

Versailles dismembered the vast sprawl of Austria-Hungary. The Allies placed priority on breaking up the Hapsburg Empire. To have merged Austria with Germany would have left a larger, more populous nation than in the Kaiser’s time, Churchill never denied Germany’s grievances over penalizing clauses in the Versailles Treaty, but he misunderstood how Austrians felt. There is little doubt that most wanted Anschluss—union with Germany—from the time of Versailles on. Churchill did not accept this, and he was wrong. He was not wrong, however, about the option of resistance.

Toward Anschluss

On 23 March 1931, without informing the League of Nations, Austria and Weimar Germany concluded a customs union, causing protests, but no action, by France and Britain.

In May 1935 Hitler declared that he had no evil intent toward anyone. The Reich had guaranteed French borders, he said, including Alsace-Lorraine. Germany “neither intends nor wishes to interfere in the internal affairs of Austria, to annex Austria, or to conclude an Anschluss.” The Times editor Geoffrey Dawson called Hitler’s speech “reasonable, straightforward and comprehensive…. [It] may fairly constitute the basis of a complete settlement with Germany.” As he wrote, Nazi street gangs were again active in Vienna. Ten months later Hitler marched into the Rhineland.

German approaches to Churchill

In early 1937, with Hitler’s approval, his ambassador to Britain von Ribbentrop invited Churchill to the German Embassy. He said he wanted to explain why the Reich was no threat to Britain. It is a mystery why Hitler approved his meeting with the Englishman he had refused to see in 1932, who was still politically powerless. But British hard-liners had begun to crystallize around Churchill, so muting him was worth a try.

Leading Churchill to a large wall map, Ribbentrop showed him Hitler’s desiderata. Adding Poland, Ukraine and Byelorussia, a “Greater German Reich” would span 760,000 square miles. (Germany was then 182,000, Britain 89,000.) In exchange for British acquiescence, “Germany would stand guard for the British Empire in all its greatness and extent.”

Had Churchill been the diehard imperialist as portrayed by modern media, one might expect he’d have gone along. Instead he said Britain would “never disinterest herself in the fortunes of the Continent.” Ribbentrop “turned abruptly away.” He then said, “In that case, war is inevitable. There is no way out. The Führer is resolved. Nothing will stop him and nothing will stop us….” Churchill with his vast memory recalled his reply:

When you talk of war, you must not underrate England. She is a curious country, and few foreigners can understand her mind. Do not judge by the attitude of the present Administration. Once a great cause is presented to the people, all kinds of unexpected actions might be taken by this very Government and by the British nation… If you plunge us all into another Great War she will bring the whole world against you, like last time.

Case Otto

Hitler’s preparations for Anschluss, “Case Otto,” were completed by 1938. On February 12th, Austrian Chancellor Kurt von Schuschnigg was summoned to Berchtesgaden. Hitler gretted him with threats of immediate invasion.

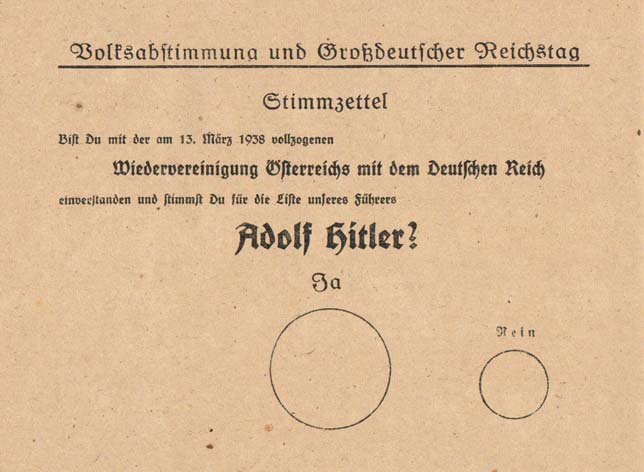

Schuschnigg was no democrat. As head of the right-wing Fatherland Front he ruled by decree, with anti-Semitic leanings similar to Hitler’s. Still, he was determined to preserve Austrian independence. Defying Hitler, he scheduled a plebiscite on March 13th, hoping to get a “no” vote by legalizing the outlawed socialists. Believing Austrian youth to be pro-Nazi, he raised the voting age to 24.

He was not given the chance. Austrian Nazis seized control of the government on March 11th, cancelling the referendum.

Annexation

Nazi troops entered the country and Hitler formally annexed Austria on March 12th. In a plebiscite a month later, 99.7% supposedly voted “Ja.”

Churchill argued that most Austrians opposed the Anschluss. His cousin, Unity Mitford, told him that the only Austrians against union were aristocrats: “Anschluss with the Reich was the great wish of the entire German population of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, long before the war and long before Hitler was even born, though the English press would make one believe that it was the Führer who invented the idea.”

Mitford was a Hitler sycophant, but in this case she was right. Yet from the standpoint of realpolitik, it mattered not what the Austrians wanted. The Anschluss was a clear violation of the Versailles Treaty. Resistance might have precluded much that followed.

Churchill’s Prescriptions

At the plenary level, the Anglo-French muted their reaction to the Anschluss. Mussolini, as Hitler predicted, said nothing. In Parliament Churchill recognized the implications:

Vienna is the center of all the communications of all the countries which formed the old Austro-Hungarian Empire…. A long stretch of the Danube is now in German hands. This mastery of Vienna gives to Nazi Germany military and economic control of the whole of the communications of south-eastern Europe, by road, by river, and by rail….the three countries of the Little Entente may be called Powers of the second rank, but they are very vigorous States, and united they are a Great Power…. Rumania has the oil; Yugoslavia has the minerals and raw materials. Both have large armies; both are mainly supplied with munitions from Czechoslovakia.

Only months later, Neville Chamberlain would refer to Czechoslovakia as “a far-away country…of whom we know nothing.” Churchill knew something. The Czech army was three times the size of Britain’s and the Czechs were major munitions producers. They were “a virile people; they have their treaty rights, they have a line of fortresses, and they have a strongly manifested will to live freely.”

Churchill did not propose military action. What he wanted was to confront Hitler with a union of powers: “What is there ridiculous about collective security? The only thing that is ridiculous about it is that we have not got it.”

“Nothing that France or we could do…”

But to Chamberlain, the idea was ridiculous:

…the plan of the “Grand Alliance,” as Winston calls it, had occurred to me long before he mentioned it…. It is a very attractive idea [but] you have only to look at the map to see that nothing that France or we could do could possibly save Czechoslovakia from being overrun by the Germans, if they wanted to do it…. I have therefore abandoned any idea of giving guarantees to Czechoslovakia, or the French in connection with her obligations to that country.

Basing so momentous decision on geography alone is incomprehensible. A mobilized Royal Navy and French Army, together with either Austria’s eighteen divisions and the Czech army dug in their border, might have given pause even to Hitler.

“Nahezu katastrophal”

Another reason favored resistance to Anschluss: the Wehrmacht was experiencing a mechanical breakdown rate of up to 30%. This was not its only problem, as Alexander Lassner wrote:

Officers and men arrived late to their posts…mis-assigned or simply untrained for their duties. Wagons and motorized vehicles were frequently missing, inadequate for their tasks or unusable. Indeed, the German VII Army Corps alone described its supplementary motorized vehicle situation as “nahezu katastrophal” (almost catastrophic), with approximately 2800 motorized vehicles which were either missing or unusable…. Poor discipline, lack of training, and outright incompetence worsened matters, as did mechanical breakdowns and lack of fuel…

Like some great malfunctioning clockwork, the Wehrmacht lurched and shuddered towards the Austrian capital. Only a few parts of it finally grated to a halt in the suburbs of Vienna one week later. Even this dismal performance was only possible due to vital and essential assistance rendered to the Wehrmacht by Austrian gas stations, and shipping and rail services. Without this help, Hitler’s victory parade on the Ringstraße would have been conspicuously devoid of German troops and armor.

Nevertheless, as with the North Vietnamese Tet Offensive thirty years later, operational disaster does not equal military disaster. The Nazi propaganda machine, parts of which were busy running down German soldiers in their rush to get to Vienna on 12 and 13 March, would prove as successful as it had ever been. (Alexander N. Lassner, “The Invasion of Austria in March 1938: Blitzkrieg or Pfusch?” in Günter Bishof & Anton Pelinka, eds., Contemporary Austrian Studies (Piscataway, N.J.: Transaction Publications, 2000), 447-87.)

Hitler’s “Tet Offensive”

Lassner’s likening of the invasion to the Tet Offensive is a striking comparison. Just as in 1968, the invaders’ unreadiness and lack of preparation went unseen. Just as ironically, German propaganda papered over the catastrophe. Like Tet, failure became triumph. Even Churchill did not comment at the time on this extraordinary display of military incompetence. Later Churchill understood, and he wrote:

A triumphal entry into Vienna had been the Austrian Corporal’s dream. Hitler himself, motoring through Linz, saw the traffic jam, and was infuriated…. He rated his generals, and they answered back. They reminded him of his refusal to listen to Fritsch and his warnings that Germany was not in a position to undertake the risk of a major conflict.”

The day before the Austrian Anschluss, Hermann Goering received the Czech Ambassador in Berlin: “I give you my word of honour,” he said affably, “that Czechoslovakia has nothing to fear from the Reich.”

One thought on “Hitler’s Sputtering Austrian Anschluss: Opportunity Missed?”

Readers might be interested to learn that in 1968, former President Dwight Eisenhower analyzed Tet too, as did Governor Ronald Reagan, who was running for president for the first time.

During my research for my book, Reagan’s 1968 Dress Rehearsal: Ike, RFK, and Reagan’s Emergence as a World Statesman, the Eisenhower Library granted me access to Ike’s post-presidential diary. In 1944 at the Battle of the Bulge, when Patton had asked Eisenhower for reinforcements to destroy the German Army, Ike immediately gave the order. But in 1968, when Ike had learned that General Westmoreland had the North Vietnamese Army and Vietcong trapped (the actual conclusion of the Tet Offensive) and asked President Johnson for reinforcements, LBJ refused and the North Vietnamese and Vietcong escaped. Eisenhower saw the clear parallels between the Bulge and Tet, and was furious at LBJ’s decision. During this time, Eisenhower had been mentoring candidate Reagan on world affairs, and Reagan then delivered a speech on Tet which attacked LBJ’s decision.

Comments are closed.