The Art of the Possible (2): Churchill, South Africa, Apartheid, Mandela

Excerpted from “Churchill, South Africa, Apartheid,” part 2 of an article for the Hillsdale College Churchill Project, June 2020. For the complete text with endnotes, please click here.

This article is dedicated to the memory of Nelson Mandela (1918-2013), below with François Pienaar after the Springboks won the 1995 Rugby World Cup. (See videos at end of article.) Not only did he support and integrate the national sport; he combined Nkosi Sikelel’ iAfrika and Die Stem van Suid-Afrika as a joint national anthem. His Churchillian magnanimity was a model for his time. And even more for ours.

“Almal sal regkom”

Continued from Part 1.

In 1994 President Nelson Mandela’s representatives asked me for the text of Churchill’s third speech to Congress. He was to address a Joint Session soon after ending Apartheid (racial segregation). I assumed he wanted the 1952 text because it was delivered (for once) in peacetime. There were no Churchill quotes in Mr. Mandela’s speech. But there was a certain echo—of which more anon.

The article prompting this essay argued that Churchill’s support of South African union helped deprive Africans of their rights. The truth is more complicated. Churchill had his faults, and some stemmed from his stubborn optimism. “Almal sal regkom,” he often remarked in Afrikaans: “All will come right.” Much has since come right in South Africa, and Churchill made his contribution.

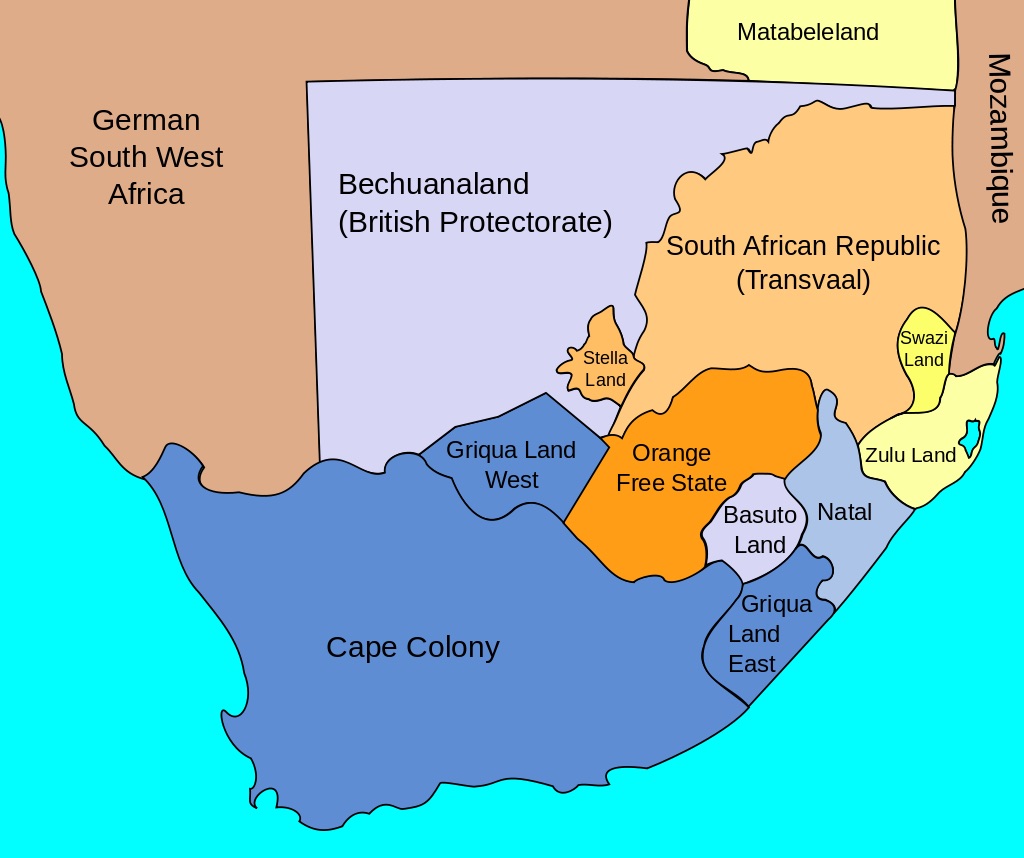

Apartheid did not begin when Britain united Natal, Cape Colony, the Transvaal and Orange Free State in 1910. It developed gradually, not taking legal form until 1949. Blacks were not everywhere disenfranchised. As Britain approved the Transvaal constitution in July 1906, Churchill and Colonial Secretary Lord Elgin strove to expand liberties against stubborn resistance.

“No cause for present apprehension”

Elgin and Churchill intended to lay the question of native rights before the cabinet. They faced several challenges. First, “nothing could be done for Africans involving the spending of British taxpayers’ money.” Second, there was the feeling: why rush? There was “no serious friction” between blacks and whites. “Each race goes its own way and lives its own life.” There was nothing like the racial animus in America, Britons told each other.

Elgin, with no experience of African Society didn’t share Churchill’s views on the rights of subjects of all colors. Natives could vote in Cape Colony, Elgin conceded. But that would end “when the whites begin to realise that political power is passing out of their hands.” Elgin thought Native councils should be established “to give them freedom to express their views.” How would those views matter? Elgin never addressed the question. “It is therefore all the more remarkable and impressive,” wrote Ronald Hyam, “that so much time was devoted to it.”

The protectorate issue

In April 1908 Lord Crewe replaced Lord Elgin as Colonial Secretary. Simultaneously, Churchill became President of the Board of Trade. This did not prevent Churchill from continuing to strive for native interests.

Churchill declared that a future South African state must concede “our right to be consulted effectively upon the native policy. I would not do anything for them without a sufficient return for the benefit of the native….” Nor should Britain jump to hand over the protectorates. What were these?

Within South Africa’s multiple components were three British protectorates. Basutoland (today’s Lesotho) and Bechuanaland (now Botswana) were established after the First Boer War (1880-81). Swaziland (renamed Eswatini in 2018) became a protectorate after the Second Boer War (1899-1902). All three, governed by native chiefs, proved a major bone of contention. For almost a century, South Africa would demand their annexation. Britain, including Churchill, found one excuse after another not to agree. Finally, in the heyday of Apartheid, Britain granted all three independence.

“Majestic, beneficent, far-reaching…”

The natives’ best security, Churchill told Crewe, was “our power to delay” handing over the protectorates. A few years would surely make a difference:

…the Government of United South Africa will take a broader and calmer view of native questions…. [And] the real security the natives are gaining in education, civilisation and influence so rapidly that they will be far more capable—apart from force altogether—of maintaining their rights, and making their own bargain…. [W]e should assert our intention to hand over the Protectorates…the more South Africa will swallow the better for House of Commons—and should then play steadily for time with all the cards in our hand. [Let us try] to get as much as we can for the natives…. The horse will draw the cart, if both are tied together. But do not let them get separated. Confront Parliament with a complete scheme, majestic, beneficent, far-reaching. Prove to them that you have done your best for the natives.

The drift toward Apartheid

On 31 May 1910 the Union of South Africa, united Cape Colony, Natal, the Transvaal and Orange Free State. Apartheid was not a word in use then. In the mainly British Cape and Natal, qualified males retained the vote regardless of race. Of course, “qualified” then required minimum income or property ownership. White women received the vote in 1930. By then, as Elgin had predicted, the black franchise in the Cape and Natal had dwindled. Successive governments of the white supremacist National Party (often known as “Nationalists”) chipped away at it, and few blacks or Cape Coloureds were still voting in the 1930s.

Two world wars kept Churchill far from South African affairs. There is no comment in his ‘tween-wars writings on the drift toward segregated societies. South Africa reasserted its claim to the protectorates. Natives should be consulted and their “full acquiescence sought,” answered Edwin Smith in 1938. “Would anyone seriously maintain that the people of this country should keep the one pledge and not the other? A promise given to Africans is just as sacred as a promise given to Afrikaners.”

Botha and Smuts

Marshal Sir Arthur Tedder (left) and Sir Alan Brooke. (War Office, Wikimedia Commons)

Churchill’s two best Afrikaner friends were former Boer enemies. Louis Botha (1869-1919), was the country’s first prime minister. Botha succeeded in making South Africa a self-governing Dominion. Prime Minister Jan Christian Smuts (1870-1950) became one of Churchill’s closest confidants.

Smuts was no egalitarian, but in his day he was considered moderate. He believed in the government by whites and “the inherent stability and good faith” of blacks. He resisted “breaking down their local tribal customs,” and opposed “the artificial half-baked white ideas we are foisting upon them.”

Malan and the Apartheid campaign

In 1946 the Fagan Commission on native laws recommended easing restrictions on natives in urban areas. It was self-serving, since it contemplated improving the supply of labor. Still, it was not Apartheid. It would have helped ease the poverty in which blacks were forced to live outside white urban areas. Smuts’s support for this reform outraged the National Party, led by Daniel François Malan, an ardent racialist. Malan fought the May 1948 election on color lines, and for the first time we heard the word Apartheid.

Smuts’s United Party ran in part on racial reconciliation—and lost. It was as surprising as Churchill’s defeat in 1945, and Smuts never got over it. He derided the Nationalists for calling his chosen successor Jan Hofmeyr a “kaffir boetie” and “gogga.” In grief and despair, he died two years later.

Smuts and Churchill

Churchill saw himself in Smuts’s defeat. “A great world statesman [was] cast aside by the country he led through so many perils and for whose independence he fought with such valour in bygone days, and for whose revival he worked with so much perseverance over long years, raising South Africa to a level of repute and influence in the world never known before.”

Malan’s drive for Apartheid depressed Smuts. The Population Registration Act of 1950 formalized identity cards specifying one’s race. The Group Areas Act ended mixed races living side by side, allotting each race its separate areas. The 1951 Prevention of Illegal Squatting Act demolished poor black neighborhoods within white enclaves. White employers had to pay for housing of any black workers allowed to reside in white cities. Laws proscribed mixed marriages. The 1953 Reservation of Separate Amenities Act reserved to whites such public facilities as beaches, buses, hospitals, schools and universities. “Whites only” signs appeared, even on park benches. Apartheid seemed at least as severe as American Jim Crow laws, which Britons once proudly claimed “don’t exist here.”

Smuts saw his country “moving into a dark period of totalitarian politics.” In 1950, Malan’s government disenfranchised Cape Coloured (mixed-race) citizens. Government bureaus ran non-white affairs. Malan, Smuts told Churchill, could not “control his republican extremists. [Their propaganda] will influence racial feeling here as no other issue can.”

Bantustans

Before he left office, Malan made another claim to the protectorates. Churchill was Prime Minister when it arrived in 1954, His response stood foursquare for justice:

There can be no question of Her Majesty’s Government agreeing at the present time to the transfer of Basutoland, Bechuanaland and Swaziland to the Union of South Africa. We are pledged, since the South Africa Act of 1909, not to transfer these Territories until their inhabitants have been consulted [and] wished it. [South Africa should] not needlessly press an issue on which we could not fall in with their views without failing in our trust.

Within fourteen years, Britain would grant all three protectorates independence. Today, Botswana is one of the most prosperous and democratic countries in Africa.

In 1958 Malan’s successor Hendrik Verwoerd set up twenty “bantustans” or black homelands, nominally independent, but recognized by no other government. Churchill had thought South Africa’s repudiating the Crown inconceivable. He was wrong. In 1961 Verwoerd proclaimed a republic, leaving a British Commonwealth increasingly critical of Apartheid.

“The oneness of the human race”

Back to Nelson Mandela’s speech to Congress. He did not quote Churchill. I preferred to think his request for Churchill’s speech meant that he shared the Churchillian spirit. There was an echo when he spoke of “the uneasy road to victory” for human rights…

Principal among these was, on the one hand, the willingness of the erstwhile minority rulers to concede political power without first resorting to such resistance as would reduce our country to a wasteland. On the other was the ability of the oppressed majority to forgive and accept a shared destiny with those who had enslaved them. That both black and white in our country can today say we are to one another brother and sister…constitutes a celebration of the oneness of the human race.

A half century before, Churchill told the House of Commons:

…when the ancient Athenians, on one occasion, overpowered a tribe in the Peloponnesus which had wrought them great injury by base, treacherous means, and when they had the hostile army herded on a beach naked for slaughter, they forgave them and set them free, and they said: “This was not because they were men; it was done because of the nature of Man.”

Ever since he asked for Churchill’s speech, I have regarded Nelson Mandela as a Churchillian. I am sure he would not approve of Churchill’s every act toward South Africa over the years. But I have no doubt that he shared two famous Churchill qualities: “In Victory, Magnanimity. In Peace, Goodwill.”

Reflections

Did everything come right in South Africa? An ex-pat friend says: “Not everything. The heady days of Mandela are long gone.” Corruption, crime and poverty still exist. “The best thing is that post-Apartheid it is not a racialistic country.” It is predominantly a two-party parliamentary system with open elections. The white population retains its economic power, but there are many black entrepreneurs, intellectuals and professionals. They are contributing much to the country.”

Was Churchill everywhere right on South Africa? No, but his efforts deserve consideration. Was his attitude paternalistic? “Of course, and you can quote Abraham Lincoln, and most of America’s founders, in precisely the same sense,” writes Hillsdale College’s President Larry Arnn:

The remarkable thing is that Lincoln, for the slaves, and Churchill, for the Empire, believed that people of all colors should enjoy the same rights, and that it was the mission of their country to protect those rights…. I do not think Churchill was typical of the age on this question, if the age was racist.

Another thing to remember is that Lincoln and Churchill were political men. Also they were democratic men. They needed, and thought it was right that they needed, the votes of a majority. If they lived in an age of prejudice (and every age is that) then of course they would be careful how they offended those prejudices.

Videos

South Africa’s dual national anthems, Rugby World Cup, 1995: Click here.

Springboks’ Captain François Pienaar looks back: Click here.