“Churchill’s Secret”: Worth a Look

Churchill’s Secret, co-produced by PBS Masterpiece and ITV (UK). Directed by Charles Sturridge, starring Michael Gambon as Sir Winston and Lindsay Duncan as Lady Churchill. To watch, click here.

Excerpted from a review for the Hillsdale College Churchill Project.

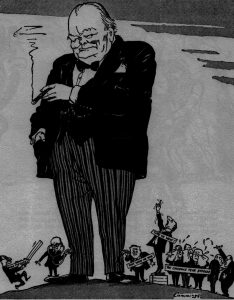

PBS and ITV have succeeded where many failed. They offer a Churchill documentary with a minimum of dramatic license, reasonably faithful to history (as much as we know of it). Churchill’s Secret limns the pathos, humor, hope and trauma of a little-known episode: Churchill’s stroke on 23 June 1953, and his miraculous recovery. For weeks afterward, his faithful lieutenants in secret ran the government. To paraphrase Dr. Johnson, the film is worth seeing, and worth going to see.

PBS and ITV have succeeded where many failed. They offer a Churchill documentary with a minimum of dramatic license, reasonably faithful to history (as much as we know of it). Churchill’s Secret limns the pathos, humor, hope and trauma of a little-known episode: Churchill’s stroke on 23 June 1953, and his miraculous recovery. For weeks afterward, his faithful lieutenants in secret ran the government. To paraphrase Dr. Johnson, the film is worth seeing, and worth going to see.

Sadness attends our mortality, death comes to us all. Sir Winston teetered in 1953; only his inner circle knew how close he had come. The “secret” has been public now for fifty years, since publication of his doctor’s diaries in 1966. But at the time it was a secret. Not a word leaked, thanks to family, staff, and three press barons—Beaverbrook, Bracken and Camrose. Private secretary John Colville wrote: “They achieved the all but incredible, and in peace-time possibly unique, success of gagging Fleet Street, something they would have done for nobody but Churchill.”

Secret Pathos

Exactly how ill the Prime Minister really was I leave to experts. At the time, many close to him thought he would die. Colville wrote: “he went downhill badly, losing the use of his left arm and left leg.” In the film Churchill’s doctor, Lord Moran (Bill Paterson), summoned to Downing Street, finds the PM singing incoherently: “I’m forever blowing bubbles.” Great heavens, I thought, they are going to link this to Marigold….

“Bubbles” was the favorite song of a 2 1/2-year-old daughter who died in 1921. Rarely mentioned, Marigold was buried in a corner of their hearts. With poignant flashbacks, the film unfolds their memories of the loss they still deeply felt. In a moving scene, Clementine tearfully recounts Marigold’s story to her husband’s nurse. As a device for portraying her and Winston’s humanity, this is a touch of genius.

The nurse, Millie Appleyard (Romola Garai) is the film’s only fictional character. She is meant to represent “the help”—too numerous to catalogue in the space of a short film. Millie has a Yorkshire accent but her father, she tells Churchill, was Welsh: “and no fan of yours.” (WSC once allowed deployment of troops during the Welsh miners strike in 1910.) Devoted to his recovery, but always her own woman, Millie sees the job through. Confronting all challengers, she’s a perfect foil for Churchill, his wife, and their sometimes obstreperous family.

Expert Casting

Critics who say PBS dotes on British drama forget that UK theatre offers unequalled depths of talent. There are so many exceptional actors that casting lookalikes for a historical film is a relative breeze. In Churchill’s Secret, the casting is superb.

Michael Gambon is an excellent Churchill: more drawn, less cherubic, but perfect in his mannerisms and bearing. Lindsay Duncan as Clementine is almost up to the standard set by Vanessa Redgrave, brilliant alongside Albert Finney’s Churchill in “The Gathering Storm” (2002)—and far superior to Sian Phillips, the great Robert Hardy’s opposite number in “The Wilderness Years” (1981).

Supporting actors are outstanding. Colville (Patrick Kennedy) and Christopher Soames (Christian McKay)—who bore the burden of state in those anxious days—could not be more lifelike. R.A. “Rab” Butler (Chris Larkin)—a Chamberlainite who had never liked and hoped to replace Churchill, whom he had hoped would retire since 1945—is the same weak reed he was in life. “I hope you don’t think of me as an enemy,” says Rab to a rapidly recovering Churchill in August. The Prime Minister replies: “I don’t think of you at all, Rab.”

The portrayal of the Churchill children, boozing and bickering (correctly excepting Mary), is over-emphasized. These scenes are admittedly fiction. No one alive knows what really happened at Chartwell in those secret weeks. The family and staff I talked to never mentioned rows during those weeks. The film strives however to represent how the three elder children must have felt, and certainly acted, at one time or another. They had grown up under a great shadow in trying times. As Moran (perhaps wise before the fact) is made to remark: “There’s a price to pay for greatness, but the great seldom pay it themselves.”

What Good’s a Constitution?

More time could have been spent on how Colville and Soames held the fort while the boss recovered. Churchill once wrote a famous article, “What Good’s a Constitution?” In 1953, they must have asked themselves that question.

Today it would be impossible to keep a lid on such a secret. What they did might indeed be thought unconstitutional. Yet the nation owed a debt to those responsible lieutenants, who acted only when they knew the PM would approve. As Colville remembered:

…the administration continued to function as if he were in full control. We realised that however well we knew his policy and the way his thoughts were likely to move. We had to be careful not to allow our own judgment to be given Prime Ministerial effect. To have done so, as we could without too great difficulty, would have been a constitutional outrage. It was an extraordinary, indeed perhaps an unprecedented, situation….Before the end of July the Prime Minister was sufficiently restored to take an intelligent interest in affairs of state and express his own decisive views. Christopher and I then returned to the fringes of power, having for a time been drawn perilously close to the centre.

K.B.O.

While the testimony of insiders certainly suggests a close call, many were confident that Churchill would recover. The morning after the stroke, wrote Mary Soames, he “amazingly presided at a Cabinet meeting, where none of his colleagues thought anything was amiss.” She quoted Harold Macmillan: “I certainly noticed nothing beyond the fact that he was very white. He spoke little, but quite distinctly.” By the time he arrived at Chartwell on the 25th, he was at rock bottom. Yet a month later he was well enough to be driven the three-hour journey to Chequers, the PM’s official country house, and was resuming his literary and political work.

Churchill’s Secret is replete with Sir Winston’s famous admonition in the face of misfortune, K.B.O. (Keep Buggering On.) Amid growing calls for his retirement, he was determined to stay—long enough at least for one more try at his final goal: a permanent peace. The film is not clear about how much time elapsed between the stroke and the “test” Churchill set for himself. That was the Conservative Party Conference at Margate. There on October 10th he would have to make a major, fifty-minute speech. It was do or die: We are rushed through the weeks to Margate, actually almost four months after he was stricken.

Of course he brought the house down. Jock Colville noted: “He had been nervous of the ordeal: his first public appearance since his stroke and a fifty-minute speech at that; but personally I had no fears as he always rises to occasions. In the event one could see but little difference, as far as his oratory went, since before his illness.”

“See them off, Winston”

Some observers have faulted the portrayal of Clementine in Churchill’s Secret—not for Lindsay Duncan’s skillful acting, but for the words the script has her say. To some she seems a whiny, self-centered neurotic, the very picture given in recent biography.

I honestly didn’t have that impression. At Margate Clementine tells him firmly: “See them off, Winston.” Their daughter told me Clementine had thought in June that his life was ending. The film suggests that Lady Churchill had many regrets; and she did. She genuinely believed—and had for a long time—that he had stayed too long. “Clementine bore the brunt of all this,” Mary wrote, “and her anxiety concerning his political intentions was great.”

The film establishes a reasonably accurate picture of Lady Churchill. “None of us would be here without him,” one of his children says, “And he wouldn’t be here without you.” Winston himself tells her: “I shall face anything with you, the Tories, the Russians—even death itself.”

Unlike certain frothy popular accounts, Churchill’s Secret makes it clear that come what may, Clementine was the rock on which he depended. As he said of her on many occasions: “Here firm, though all be drifting.”

One thought on ““Churchill’s Secret”: Worth a Look”

I saw this too 3 1/2 stars. Really movie quality. I loved the fact that the exteriors were shot at Chartwell (I have never been). It told a then virtually untold story to a mass audience. And like the “King’s Speech” it was sympathetic to Churchill. Of course, we who have read Moran’s diary have known the secret for years. But I had forgotten about Marigold. And this film showed the importance of a strong marital companion. I myself would not be half the man or half the father I am without mine.

Comments are closed.