Churchill, Troops & Strikers (1)

This is a time when we often question the actions of police forces. In America, governors occasionally call in the National Guard during riotous protests. Local residents are always the main victims of such events. Churchill’s experience with strikers is worthy of study, his magnanimity worthy of reflection.

Did WSC Send Troops Against Strikers?

For a century it has been part of socialist demonology that Churchill sent troops to attack strikers during a 1910 miners’ work stoppage in Tonypandy, Wales. In 1967 an Oxford undergraduate wrote that Churchill faced down strikers with tanks. This was very prescient of him, since tanks didn’t exist in 1910.

And for half a century Churchill’s defenders, beginning with his son and including this writer, insisted all this was a lie. Churchill, were said, deferred from using troops against the mineworker strikers and left law enforcement to the local constabulary.

Out of this has grown a considerable muddle, to which I have added my share. So this is to correct the record: Churchill did send troops to areas containing strikers and riots in 1910-11. He withheld their deployment in 1910, but in 1911 their presence at one location resulted in fatalities.

Now, as the traffic judge used to allow me to do in my leaded-footed days as a teenage driver, I shall plead on Churchill’s behalf: “Guilty with an explanation.”

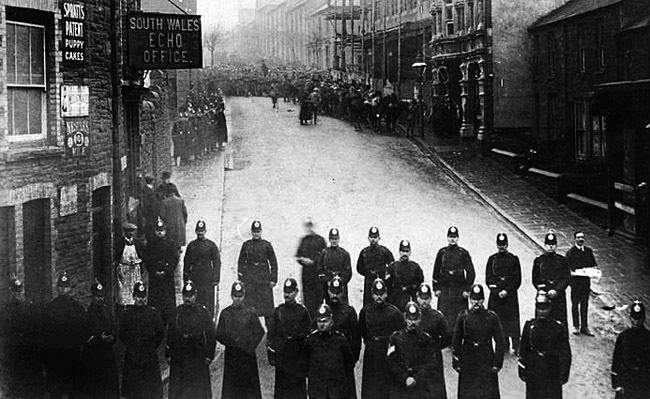

Tonypandy, Wales, November 1910

A coal miners’ strike grew out of disputes over wage differentials for working hard and soft seams. Up to 30,000 miners were involved, and local authorities appealed for troops to the Secretary of State for War, Richard Haldane, who consulted Churchill, then Home Secretary. They agreed to send police, but to station some troops nearby if worst came to worst.

Churchill reported to the King that he had restored peace without resort to soldiers. The Conservative press attacked. The Times said that he did not understand the need for “decisive handling.” The Liberal press defended him, a Liberal MP. “The brave course was also the wise one,” wrote the Manchester Guardian…“Instead of a score of cases for the hospital there might have been as many for the mortuary.”

Writing to David Lloyd George the following spring, Churchill expressed his wish to help the miners. The government, he said, should meet their requests for stronger safety regulations and inspections, given the highest death rates since mining statistics had begun—and finance the expense with a surcharge on mineowners’ royalties.

Llanelli, Wales, August 1911

Nine months later, a national railway strike broke out when rail operators refused to recognize the unions as negotiators. This time troops arrived at numerous scenes of disturbances around the country. Mostly they acted with caution, and when they did fire, they usually aimed over the heads of crowds.

Lloyd George settled the strike by convincing the railways to recognize the union negotiators. But in Llanelli, Wales—two days, ironically, after the strike had ended—the only fatalities from the use of troops occurred. Rioters held up a train and knocked the engine driver senseless. Soldiers attempted to clear the track but looting began, and they fired into the crowd, killing two or four rioters (accounts vary).

Troops left when the strike ended. On August 20th King George V telegraphed Churchill: “Glad the troops are to be sent back to their districts at once: this will reassure the public. Much regret unfortunate incident at Llanelli. Feel convinced that prompt measures taken by you prevented loss of life in different parts of the country.”

Randolph Churchill wrote in the official biography:

For all the criticism that came Churchill’s way from the Labour members of Parliament for his attitude to the use of troops during this strike, there is little doubt that the King’s telegram represented public opinion at the time. But Labour was not to forget….

Concluded in Part 2…