Churchill, Wells, and Government by “Experts”

Excerpted from “Churchill and H.G. Wells Debate Government by Experts,” my essay for the Hillsdale College Churchill Project. To read the original article with endnotes, click here. To subscribe to weekly articles from the Churchill Project, click here, scroll to bottom, and fill in your email in the box entitled “Stay in touch with us.” Your email address is never given out and remains a riddle wrapped in a mystery inside an enigma.

Churchill to Wells, 1901-1931

“Change, even for the better, [man] accepts doubtfully & thanklessly; he knows science & civilisation will not give him Happiness… and he has no intention of putting himself in the hands of amiable but pitiless philosophers, to be regulated and informed as if he were a breed of short horns.” —Winston S. Churchill to H.G. Wells, 17 November 1901

“Projects undreamed-of by past generations will absorb our immediate descendants; forces terrific and devastating will be in their hands; comforts, activities, amenities, pleasures will crowd upon them, but their hearts will ache, their lives will be barren, if they have not a vision above material things.” —Winston S. Churchill, “Fifty Years Hence,” Strand Magazine, December 1931

Clubbable adversaries

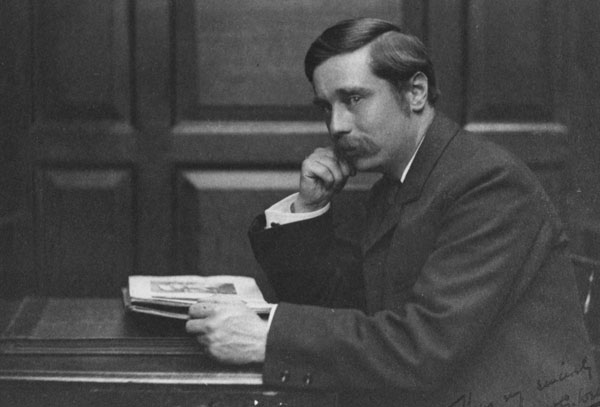

Churchill admired the great futurist H.G. Wells (1866-1946) as fervently as he disagreed with him. In youth they argued over the roles of experts in government. Their debate mirrors modern arguments over Anthony Fauci and the Regulatory State. But there is no attempt here to draw comparisons. The reader may decide what lessons the Wells-Churchill dialogue offers.

The two made contact in November 1901. Both were by then established authors. Their relationship lapsed during the First World War, for Wells held Churchill responsible for the Dardanelles debacle. Still, Wells was welcomed into The Other Club, whose “the pious founder” loved gifted literati.

Wells died in 1946, agreeing with Churchill about nuclear proliferation and Western unity. Our focus here, however, is their early debate over government by experts—when Churchill was only 23 and Wells 35. For Churchill’s and Wells’s later relationship, see Fred Glueckstein, “Great Contemporaries: Churchill and H.G. Wells, the Two Futurists” (2018).

Tory grandee and Fabian socialist

Jonathan Rose offers a comparison of Churchill and Wells at the time they met:

[Winwood Reade’s] The Martyrdom of Man, which looked forward to space travel and other technological marvels… was profoundly inspirational for both… even if they drew different lessons from it. They were both progressives but they had divergent conceptions of progress. For H.G. Wells, who would join the Fabian Socialists, it meant rigorous scientific planning by technocrats. For Churchill it meant muddling through by aristocrats, and he was far less willing to sacrifice human freedom for the sake of a better future.

Their chief correspondence concerns Wells’s books. In 1899, Wells’s When the Sleeper Wakes and Churchill’s Savrola both concerned democratic revolutions, although the former was set 200 years in the future, while Churchill focused on the present. But there is no indication in their letters that Wells had even read Savrola, much less critiqued it. Churchill, by contrast, gobbled everything of Wells that he could find.

“Good Lord deliver us”

In late 1901, the publisher sent Churchill a pre-publication copy of Anticipations, another Wells vision of the future. It anticipated a republic—later a “world state”—governed by “capable, rational men.” Their differences are interesting given the world we live in today, which in many ways seems to be governed by experts.

The precocious young Winston declared there was much in Anticipations “which I cannot accept”:

Nothing would be more fatal than for the government of States to get into the hands of the experts. Expert knowledge is limited knowledge: and the unlimited ignorance of the plain man who knows only what hurts is a safer guide, than any vigorous direction of a specialised character. Why should you assume that all except doctors, engineers etc., are drones or worse?

To manage men, to explain difficult things to simple people, to reconcile opposite interests, to weigh the evidence of disputing experts, to deal with the clamorous emergency of the hour; are not these things in themselves worth the consideration and labour of a lifetime? If the Ruler is to be an expert in anything he should be an expert in everything; and that is plainly impossible. Wherefore I say from the dominion of all specialists (particularly military specialists) good Lord deliver us.

“Easy to lead and hard to drive”

Churchill pressed Wells: “Human nature is a much more intractable and masterful thing than your speculations admit…. We shall not change so quickly as you think.” (His views hadn’t changed 30 years later when he wrote: “It is at once the safeguard and the glory of mankind that they are easy to lead and hard to drive.”)

“I too will most heartily join in the ‘God shall deliver us,’” replied the not-yet-quite-atheistic Wells. But the leaders he envisioned would be “educated not trained.” He thought Churchill prejudiced by his class:

If you could be transported by some magic into the Household of your ancestors of 1800, a week would make you at home with them…. But of the four grandparents who represented me in 1800 it’s highly probable two could not read and that any of them would find me and that I should find them as alien as contemporary Chinese. I really do not think that your people who gather in great country houses realize the pace of things.

While valid, this greatly underestimated Churchill. Even then he had a grasp of the problems of ordinary people that would soon drive him to the reforming Liberal Party. Nor could Wells quell the younger man’s passion for liberty. “You must not be too impatient with the politician,” Churchill told him. It was a politician’s duty “to protect millions of imperfect people who merely wish to remain comfortable against those who on the one hand would make them perfect…”

Bingo. But 12 decades later, do we still resist those who would make us perfect?

“Big sliders and new fissures”

Wells was not put off by Churchill’s challenges. “To me,” he wrote, “you are a particularly interesting and rather amiable figure….

Believing as I do that big sliders and new fissures are bound to come in the next few years…. I speculate whether you anticipate that when you are 60 you will be in or upon a Conservative Party with a Liberal opposition and an Irish Corner in a British or Imperial Parliament and if not—where you expect to be.

Churchill was a Conservative at 60, but the opposition was by then socialist, and the “Irish Corner” had vanished. Nor, at 60, was he where he expected to be.

Churchill shared Wells’s faith in science, but he never lost his reservations about experts. Four months after they met, he declared in Parliament: “It was a principle of our Constitution not to employ experts, whether business men or military men, in the highest affairs of State.”

Five months before Wells’s death he reiterated: “Expert knowledge, however indispensable, is no substitute for a generous and comprehending outlook upon the human story with all its sadness and with all its unquenchable hope.”

Parallel reading

“The Social Dilemma and Churchill’s ‘Mass Effects in Modern Life,'” 2021.

“How Churchill Saw the Future: Prescient Essays, 1924-1931,” 2018.

One thought on “Churchill, Wells, and Government by “Experts””

Five months before Wells’s death Churchill reiterated: “Expert knowledge, however indispensable, is no substitute for a generous and comprehending outlook upon the human story with all its sadness and with all its unquenchable hope.” GREAT QUOTE. Of course what Churchill is speaking of his not merely information or technology BUT WISDOM.

Comments are closed.