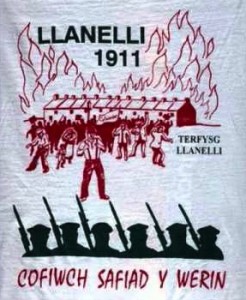

Churchill, Troops and Strikers (2): Llanelli, 1911

Llanelli in Context

Llanelli and the Railway Strike: concluded from Part 1…

Throughout the August 1911 railway strike, troops stood by. Their orders were to interfere only against threats to public security. But there was another reason why anxiety ran high at that time. A few weeks earlier, the Germans had sent a gunboat to Agadir, French Morocco. Rumors of war with Germany were rampant. David Lloyd George said the Agadir Crisis was a threat to peace. The Germans, he warned, “would not hesitate to use the [strike] paralysis,,,to attack Britain.” Paul Addison, in Churchill on the Home Front, described the public mood. A simultaneous national railways stoppage alarmed the nation. Fear of German subversion also worried Churchill:

He was also informed by Guy Granet, the general manager of the Midland Railways, of allegations that labour leaders were receiving payments from a German agent….Conservatives applauded him for taking decisive action. But there were loud protests from the Labour party and left-wing Liberals, who accused him of imposing the army on local authorities against their will, and introducing troops into peaceful and law-abiding districts.

“Guilty with an Explanation”

What Churchill’s critics could not see, Ted Morgan wrote, “was the number of saved, and the number of tragedies averted. In their drunken frenzy, the Llanelli rioters had wrought more havoc and shed more blood and produced more serious injury than all the fifty thousand soldiers all over the country.”

After the deaths at Llanelli, Churchill was roundly condemned and the Manchester Guardian, which had praised him after Tonypandy, now turned against him. Keir Hardie, founder of the Labour Party, accused Churchill and Prime Minister Asquith of “deliberately sending soldiers to shoot and kill strikers.” That exaggeration has endured for a century. Yet Churchill in August 1911 was clear in the House of Commons. “There can be no question of the military forces of the crown intervening in a labour dispute.”

After the deaths at Llanelli, Churchill was roundly condemned and the Manchester Guardian, which had praised him after Tonypandy, now turned against him. Keir Hardie, founder of the Labour Party, accused Churchill and Prime Minister Asquith of “deliberately sending soldiers to shoot and kill strikers.” That exaggeration has endured for a century. Yet Churchill in August 1911 was clear in the House of Commons. “There can be no question of the military forces of the crown intervening in a labour dispute.”

Why did they at Llanelli? Defending himself in a handwritten letter to a Manchester Liberal colleague, Churchill considered both sides of the argument:

The progress of a democratic country is bound up with the maintenance of order. The working classes would be almost the only sufferers from an outbreak of riot & a general strike if it c[oul]d be effective would fall upon them & their families with its fullest severity. At the same time the wages now paid are too low and the rise in the cost of living (due mainly to the increased gold supply) makes it absolutely necessary that they sh[oul]d be raised. a I believe the Government is now strong enough to secure an improvement in social conditions without failing in its primary duties.

Old Men Remember

Among those interviewed by the BBC fifty-five years later for their memories of Tonypandy was W.H. (Will) Mainwaring, one of the youngest militants in the South Wales coalfields, who was subsequently co-author of a famous pamphlet, The Miners’ Next Step. Over fifty years later he still spoke with pride of his record as a strike leader.

Of Churchill’s decision to send troops into the Rhondda in 1910, Mainwaring said on camera:

We never thought that Winston Churchill had exceeded his natural responsibility as Home Secretary. The military did not commit one single act that allows the slightest resentment by the strikers. On the contrary, we regarded the military as having come in the form of friends to modify the otherwise ruthless attitude of the police forces.

Sources:

BBC documentary: The Long Street: Road to Pandy Square (1965)

Paul Addison, Churchill on the Home Front 1900-1955 (London: Jonathan Cape, 1992), 250-52, and correspondence with the author, 2014.

Martin Gilbert, Churchill’s Political Philosophy (London: British Academy, 1981), 96.

Randolph S. Churchill, Winston S. Churchill, vol. 2, Young Statesman 1901-1914 (Hillsdale, Mich.: Hillsdale College Press, 2007), 385-86.

Ted Morgan, Churchill: The Rise to Failure 1874-1915 (London: Jonathan Cape, 1983), 328.

3 thoughts on “Churchill, Troops and Strikers (2): Llanelli, 1911”

Not used in 100 years, you both say? But what about those sent to the Battle of George Square in Glasgow in January 1919, to quell that strike?

–

They were not deployed against strikers. The facts are reprised here by Scottish historian Gordon Barclay, who writes:

It is true that Glasgow’s chief legal officer Alistair Mackenzie, Sheriff of Lanarkshire, called for troops when he was struck by a missile during rioting, but he called for them to stem a riot, not put down a strike. They stood about guarding things, and were certainly visible on the streets while they were there. Barclay also shows that Churchill, though it wasn’t his decision, warned against sending them, saying that

As Churchill said: “The truth is incontrovertible. Panic may resent it, ignorance may deride it, malice may distort it, but there it is.” RML

“National Guard” (in Part 1) refers to American terminology; I have amended the text to indicate. If in Britain regular or T.A. troops have not been used to quell a strike in 100 years, might we conclude the Llanelli was the last time?

We do not have a National Guard in the U.K. As far as I am aware in the past 100 years troops i.e.regular and /or T.A.(now Army Reserve) have only been used to maintain essential services e.g.firefighters.

Comments are closed.