“A Good House of Commons Man”: Robert Rhodes James

Excerpted from “Great Contemporaries: Sir Robert Rhodes James,” written for the Hillsdale College Churchill Project. For the original article and images, click here. To subscribe to weekly articles from Hillsdale-Churchill, click here, scroll to bottom, and fill in your email in the box entitled “Stay in touch with us.” Your email address is never given out and remains a riddle wrapped in a mystery inside an enigma.

Fair and balanced

In his best-known book, Robert Vidal Rhodes James said he aimed to prove that Winston Churchill was human. He was immediately asked: wasn’t that a superfluous mission? Sir Robert replied that Churchill had been almost completely deified—so it was high time someone brought him down to earth. Churchill: A Study in Failure (1970) was a comprehensive catalogue of the great man’s outrages, miscalculations and errors which left WSC, through the late 1930s, admired for his drive and brilliance and distrusted for his supposed lack of judgement. A Study in Failure was not a pioneering work, since critical books about Churchill had been appearing since the 1920s. But it was the best of them: carefully researched, deftly argued, elegantly written, a model.

The politician-writer

Like Churchill, Sir Robert was that rare combination, a politician-writer. Unlike many today, he didn’t make politics his sole career. He clerked in the House of Commons, returned to All Souls College as a research fellow, taught history at Stanford and the University of Sussex, and worked for the United Nations in New York. In 1976 he stood as a Conservative in a by-election for Cambridge, a marginal seat. He held it despite strong challenges until he retired in 1992.

Aside from A Study in Failure, Robert left a huge corpus for laborers in the Churchill vineyard. His first book, Lord Randolph Churchill (1959), was the first biography of Sir Winston’s father since WSC’s and Lord Rosebery’s early in the century. In 1964 he published a biography of Lord Rosebery himself.

Biographies followed on Prince Albert (1983) and Anthony Eden (1986). Like most of us, he was sometimes uneven. Bob Boothby (1991) bordered on hagiography. Boothby, Churchill’s Parliamentary Private Secretary in the 1920s, who later fell out over ethical lapses, hardly puts a foot wrong in that book, which etiolates Churchill. Perhaps this was because Robert and Boothby both liked to stir the political pot. But most of the time, like Churchill, Rhodes James was a skilled politician-writer.

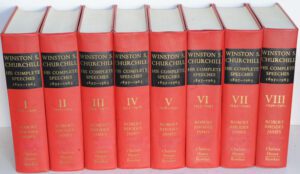

His greatest contribution was Winston S. Churchill: His Complete Speeches 1897-1963 (1974). It took up eight thick volumes, with two well-organized and comprehensive indexes. He shocked me once by confiding that he had been paid only £5000 for the whole job—55 pence per page. Out of that he had to pay his student researchers. It’s a safe bet that he derived little from the later abridged editions, such as Churchill Speaks. But he was proud of the effort, and smiled when told it’s among the most sought-after of the multi-volume Churchill works.

Rhodes James as I knew him

I met him in Washington in 1994, where he spoke at a symposium, later quantified in Churchill as Peacemaker (1997). He sniffed that his hotel room lacked the bottle of whisky he’d enjoyed at his last symposium in Texas. He was affronted by America’s no-smoking diktat, then almost universal: “In a few year’s time everything in your country will be illegal, except sex between consenting adults of the correct persuasion. I like smoking. Oh dear.” One evening the ebullient James Humes, after too good a dinner, introduced Lady Rhodes James as “an English rose.” Robert murmured, not quite sotto voce, “Who is that dreadful man?”

At our symposium he griped that speakers had to stand up, then took on Professor Manfred Weidhorn, who said Churchill objected to Hitler’s occupation of the Rhineland. Walking briskly to the podium after Manny’s presentation, Robert announced: “Churchill said nothing about the Rhineland, nothing at all. He was hoping to get into the Cabinet and so he kept his mouth shut.” Then bang, he sat down again. No questions, thanks very much.

Nevertheless we found Robert a grand personality, full of stories about Churchill and Parliament. Paul Addison remembered “what fun he was to be with. Such a warm and generous character—he sparkled with gossip and was full of enthusiasms.”

The Washington Post said Robert “could be a congenial companion to those he counted as his intellectual near-equals.” But he “never lost the superior manner commonly displayed by clerks of the House of Commons.” On balance Sir Robert remained pro-Churchill, and hoped to write a post-1939 volume entitled A Study in Success.

Tory Wet

I was sure that Robert and I weren’t destined to become chums. He was a “Tory wet” (think RINO Republican, conservative Democrat). He believed in Little Britain within the European Union, and regarded Margaret Thatcher as a rather nasty aberration. I was a right winger who had voted for Goldwater and Reagan and Steve Forbes, and would have voted Thatcher if I could, who believed that the EU was a globalist con-job for the benefit of the Franco-Germans. The best Great Britain could do was to revive Commonwealth Free Trade and join the North American Free Trade Association. (Oh dear, indeed.)

We disagreed about the Churchill Official Biography. Randolph Churchill had sacked Robert from his research team of “young gentlemen,” and Robert never forgave him (or his dislike of Eden). He always maintained that the O.B. was the same “case for the defence” Sir Winston had already made in his own books. Robert always said exactly what he believed—in the most forceful terms available to a gentleman. In an age of prevaricating phonies of Left and Right, such a character is rare. Winston Churchill would have loved him.

Flogged then forgiven

We tangled over the Rhineland issue, because Churchill did and said things about it which ought to be considered. Sweeping generalizations, I argued, have no place either in a biography or a seminar. Robert ended the discussion with a preemptory note. “I am one of Churchill’s strongest admirers, but I cannot accept claims that have no merit or justification. I see no point whatever in continuing this correspondence.”

And that, I thought, was that. Yet a year later he wrote to offer me a very good piece: “Myth-Shattering: An Actor Did NOT Give Churchill’s Speeches.” Instantly we renewed our correspondence, in which I was rewarded with a treasury of keen observations.

Robert’s shrewd thoughts on Churchill and politics, delivered ad hoc with an entre nous intimacy, were a privilege to read. (I share some below, all food for thought.) He even agreed to consider whatever I would write about Churchill and the Rhineland. I came to realize that here was a wise and opinionated Diogenes, to shed a kindly light over my own insignificant Churchill studies.

Alas the Rhineland piece was set aside, because like most of his friends and admirers I expected Robert would be with us a good while yet. Now if I write it, he will never read it, and then hammer me in cordial debate.** He died too young, of cancer on 20 May 1999, his second Churchill volume unpublished. I mourned the loss of a first class intellect and, as Churchill said on occasion, “a good House of Commons man.”

**See “Churchill and the Rhineland: ‘They Had Only to Act to Win.'”

Robert Rhodes James on Churchillians

From correspondence with the author, 1995-98.

Anthony Eden

“I do not think that WSC developed ‘a cold hatred’ for Eden; certainly their correspondence would belie this. But the abandonment of the Suez Canal base in 1956 angered Churchill, as did Eden’s manifest impatience with WSC’s procrastination about retiring.”

George VI

“The relationship between Churchill and the King during the war is important. It has been consistently underestimated, and even on occasion ignored. It began stickily but developed into the closest collaboration between monarch and prime minister in modern British history. The Queen Mother was very affectionately amusing about WSC, as was the King when Churchill’s letters became especially flowery. On one occasion WSC enthusiastically responded to a plea for help in preparing a broadcast by the King. He sent His Majesty a speech he had composed specially. Of course, it contained words and phrases the King could not get his tongue round. While splendidly Churchillian, was so out of character for the King that it was politely rejected. Sadly, his draft seems to have disappeared.”

Harold Nicolson

“His position was Parliamentary Secretary to the Ministry of Information between May 1940 and June 1941. This was a junior ministerial post in the Churchill Coalition Government. Alfred Duff Cooper was a disaster as Minister, and Harold’s career suffered thereby. But as his son Nigel has frankly admitted, ‘he was not a fit person to run a department in wartime.’ Indeed, much as I loved Harold, he was marvellously unfitted to administer or run anything. When WSC, who needed a Labour minister to balance the Coalition team, had to sack Harold, whom he greatly liked and respected, he made him a governor of the BBC. This was his true métier.”

Alfred Duff Cooper

“I too thought that John Charmley’s biography of Duff Cooper was much better than his Churchill book, though I thought he was unduly censorious about Duff’s drinking and womanizing. If his wife was tolerant of both, then I think we can be. I prefer red-blooded people to time-servers and sycophants. And Duff had real guts, in war and peace. And he wrote so wonderfully, gracefully and simply—particularly on a hot summer afternoon after a long lunch with beautiful women and plenty of champagne, good wine, and brandy. But this is now terribly unfashionable and non-PC!”

Lord Randolph Churchill

“I never believed the canard that he died of syphilis. When I was researching my Lord Randolph Churchill in the 1950s I discussed it with an eminent elderly specialist in the disease. He told me that, having looked at the symptoms, syphilis was the least likely cause of his decline and death. He was certainly treated for it, by a physician who was on public record as declaring that all nervous diseases were syphilitic. This, of course, we now know is nonsense. John Mather’s conclusion that the treatment only accelerated Lord Randolph’s mental collapse and death seems to me to be fully justified.

I am rather surprised that some of the Churchills told you they believed the story, although Randolph, ill-advised as usual, did. But the Churchills do like to tease. Clarissa Avon [WSC’s niece who married Eden] once told me that ‘of course’ her father Jack was illegitimate, knowing full well that this was nonsense, but rather chic. Jack’s son John was physically almost an exact replica of his Uncle Winston, and with an even more formidable capacity for alcohol. He lived to a much greater age than the modern Puritans deem possible, and was also a very good artist.”

The following, just resurfaced, were not in my original post but shed more light on the great character he was….

Churchill symposia

“I am glad your last Symposium went much better, and the style that I had advised was adopted. The great Austin Conference on WSC* was made memorable and enjoyable by the provision of the smoking room in the LBJ Library, and, by a stroke of added genius by Roger Louis, a bottle of bourbon for each participant. No wonder it was a triumph. And WSC would have greatly approved.” *Published as Churchill: A Major New Assessment of His Life in Peace and War, Lord Blake and William Roger Louis, editors (1993).

WSC’s grandsons?

“We had a fine dinner meeting of The Other Other Club in Madison. I cut down my contribution drastically, as the old boys were longing to get at their oysters and Pol Roger…. I did the same at the Anniversary meeting in Zurich, where I spoke from the same podium as WSC had in 1946. Alas the Swiss Foreign Minister gave an interminable and hardly relevant speech, Mine went well, and there were many requests afterwards for the full text. The Swiss Press got rather confused and described Nicholas Soames and me as WSC’s ‘two grandsons.’ This puzzled the multitude, as the physical resemblance is absolutely nil. Nicholas, of course, thought it hilarious.”

The weed

“If we have another Winston Churchill symposium it really must recognise that a non-smoking Churchill Conference is a contradiction in terms, almost as idiotic as a non-smoking Churchill Cabinet! Auberon Waugh has formed a club in London in which smoking is compulsory. This may be taking the counter-revolution rather too far, but he is making a point against the PC fanatics.”