Train-Spotting: Churchill’s Reputation in the First World War

Will Boris Johnson’s political career survive “Pinchergate” and “Partygate”? Will Donald Trump’s reputation outlast January 6th, 2021? Who knows? Mr. Johnson likes to channel Churchill, whose rehabilitation after the Great War took 20 years to complete. We should deprecate silly comparisons, but Churchill did make his share of comebacks: 1906, 1917, 1924, 1939, 1951…

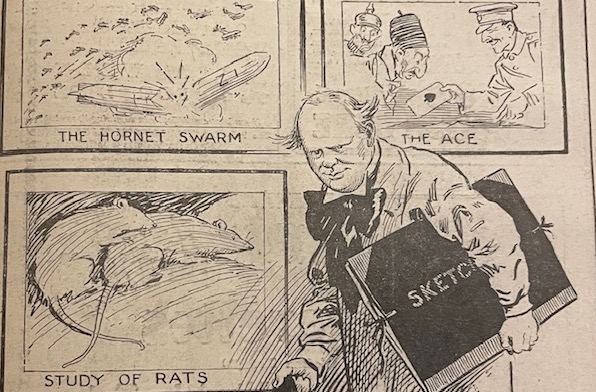

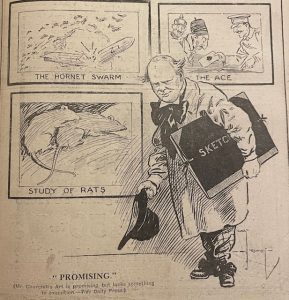

Tim Benson of the Political Cartoon Gallery asked for help puzzling out two obscure cartoons attacking Churchill’s reputation. Both are over 100 years old. The first was “Promising,” by Charles Crombie, published 30 October 1915. Churchill’s art, reads the caption, “lacks something in the execution.” Artist Churchill is shown with three sketches lampooning his pugnacious pronouncements and unwarranted optimism.Neither Tim nor I could at first grasp the point they were making. Andrew Roberts came to our rescue with key pointers.

This exercise is the kind of thing a critic of Churchillians once labelled as “train-spotting.” Who cares? It teaches things about how low a political reputation can sink and still come back. All this, yet he was prime minister by 1940.

“Study of Rats”

On 26 May 2015, betrayed by the resignation of First Sea Lord Admiral Fisher, Churchill was sacked from the Admiralty. One reason was the growing debacle of the Dardanelles and Gallipoli. Those operations were regarded, inaccurately, as Churchill’s inventions. He had been among their strongest advocates. His words, before and after his departure, attached to him like limpets.

Martin Gilbert wrote: “The criticisms levelled at Churchill covered, as he knew, every aspect of his work at the Admiralty; even the phrases which he had used in his speeches.” [1] An early example came in September 1914, when Churchill addressed a loud, partisan crowd in Liverpool:

The navy cannot fight while the enemy remains in port [laughter]—but despite this we are enjoying the command of the sea as fully as if the German navy had been destroyed. Although we hope that a decision at sea will be a feature of this war, although we hope that our men will have a chance of settling the question with the German fleet, yet if they do not come out and fight in time of war they will be dug out like rats in a hole. [2]

Pushback

Despite cheers from the audience, the Establishment thought his words undignified. Worse, the very next day, the Germans sank three British cruisers, HMS Aboukir, Hogue and Cressy, near the Dogger Bank. The King’s private secretary observed, “the rats came out of their own accord.” Churchill was blamed for the deaths of 1459 sailors. [3] Ironically, four days earlier, alarmed at the risk the old cruisers were taking, he had ordered their withdrawal. But the “mainstream media” of the time preferred to engage in “disinformation.” Nothing new under the sun….

By late 1915 Churchill’s reputation was already low over the Dardanelles and Gallipoli. So it was not hard to associate Crombie’s “Study of Rats” with WSC’s “rats” speech and the loss of the warships. But what about the other two Churchill sketches?

“The Hornet Swarm”

I searched for “hornets” in the Hillsdale College Churchill Project’s scans of Churchill’s words. By sheer chance, one of the first quotes associated hornets with Zeppelins—the German airships which began attacking London in 1915. Martin Gilbert explains that Churchill once referred to the British fighter pilots as hornets: “This description had subsequently been criticized as derogatory to the pilots.” [4] The criticism stuck to Churchill for years. In 1916 he was still defending himself:

My hon. Friend the Member for Brentford (Mr. Joynson-Hicks) has twitted me this afternoon with my phrase about “hornets.” I am very glad to come to the “hornets.” The main defence of England against Zeppelins has consisted since the War began in that formidable “swarm of hornets” of which I spoke in 1913—that is to say, aeroplanes with skilful pilots held ready with bombs and guns to attack any Zeppelin which approaches our shores. [5]

Churchill was angry that “Jix” had criticized his efforts to build up the Royal Naval Air Service, Zeppelin raids were only successful at night, he insisted, “because it has proved very difficult indeed, and almost impossible, to find the Zeppelin in the dark.” [6] During the war, 568 Britons were killed and over 1000 injured in Zeppelin raids. Then came the incendiary bullet, which pierced airship gasbags and ignited their hydrogen. Germany withdrew its airship bombers after June 1917. But Churchill, long blamed for the Dardanelles, was easy to criticize, despite his efforts to thwart the Zeppelins and even to bomb their base at Friedrichshafen.[7]

“The Ace”

Crombie’s third Churchill “sketch” was challenging. A British officer playing a winning card against a Turk, to the surprise of the German Kaiser? What could it mean? Andrew Roberts put us on track: “The card is the ace of spades—a key fort on the Gallipoli Peninsula….”

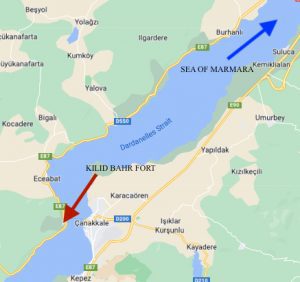

The Narrows of the Dardanelles were guarded by forts. On the European side was a fort at Kilid Bahr, known as the “Trefoil” or “Ace of Spades.” It was key to the Gallipoli invasion:

This was the plan: The British 29th Division, backed up by French troops, were to carry out the main landings at five beaches on Cape Helles, with the Kilid Bahr Plateau as their main objective. The plateau commanded the Kilid Bahr forts, overlooking the Narrows—the narrowest section of the Dardanelles. If they could silence those forts, the navy had a chance of clearing the remaining mines and getting through the Dardanelles, into the Sea of Marmara and on to Constantinople. This had, after all, been a naval operation right from the start. [8]

On 20 May 1915, the Allies did silence the “Ace of Spades” and other Narrows forts. Optimists including Churchill thought their capture might enable the Narrows to be cleared of mines for a naval breakthrough. [9] It was not to be, and the invasion languished with great losses for the ANZAC and British forces. Thus the cartoon: three Churchill “promises” that fell short in execution.

Ironically, Lord Fisher had already resigned when the “Ace of Spades” fell, and Churchill was sacked a week later. By October, Gallipoli was nearing evacuation. Churchill, his reputation shattered, would soon leave the cabinet and report to the front. We may understand why he saw events as snatching defeat from the jaws of victory.

“Taboo!”: Edward Tennyson Reed, 1917

This opened a rift that found Lloyd George excoriating Northcliffe’s “diseased vanity” in 1919. [10]

Lord Roberts adds that Churchill’s name was also mentioned for the Air Board, owing to his interest in and founding of the Royal Naval Air Service. (Eventually there was an Air Ministry, and in 1919 Churchill was appointed to head it.)

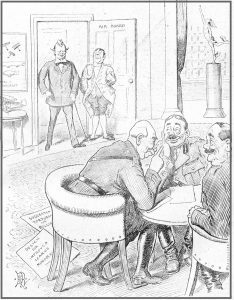

Thus the “warning cartoon” by E.T. Reed, well known for his many works in Punch. Air Board factotums warn each other not to mention rats or hornets—dog whistle pejoratives when applied to Churchill. And WSC was constantly accused of being a windbag.

Train-spotters to the rescue: Two obscure cartoons are deciphered. With thanks to Andrew Roberts and Tim Benson.

Endnotes

- Martin Gilbert, Winston S. Churchill, vol. 3, The Challenge of War 1914-1916 (Hillsdale, Mich.: Hillsdale College Press, 2008), 764.

- Winston S. Churchill (hereinafter WSC), “Rats in a Hole,” Tournament Hall, Liverpool, 21 September 1914, in Robert Rhodes James, ed, Winston S. Churchill: His Complete Speeches 1897-1963, 8 vols. (New York: Bowker, 1974), III: 2336-37.

- Gilbert, Challenge of War, 86.

- Ibid., 765.

- WSC, “An Air Ministry,” House of Commons, 17 May 1916, in Complete Speeches III: 2416.

- Ibid.

- In October 1914 Churchill smuggled Sir Osmond Brock into Germany to gather intelligence on the Friedrichshafen Zeppelin base. The information led to the world’s first strategic bombing mission, on 21 November. The damage was slight, but it did offer a propaganda coup. (Andrew Roberts points out that Churchill also referred to the Zeppelin sheds as “a nest of hornets.”)

- The Chronicle, Toowoomba, Queensland, 11 April 2015, accessed 30 July 2022 on the Australian Press Reader.

- “Allies Silence Kilid Bahr Fort: Important Dardanelles Defense Apparently Disabled…. Fall of Nagara Reported Imminent…. Fresh Allied Troops Disembarked at Kum Kale…. Turks Hurry Big Guns from Adrianople” The New York Times, 20 May 1915.

- “Alfred Harmsworth, First Viscount Northcliffe,” in Wikipedia, accessed 30 July 2022.