Present at the Creation: Randolph Churchill and the Official Biography (1)

“Randolph Churchill: Present at the Creation,” is taken from a lecture aboard the Regent Seven Seas Explorer on the 2019 Hillsdale College Cruise around Britain, 8 June 2019.

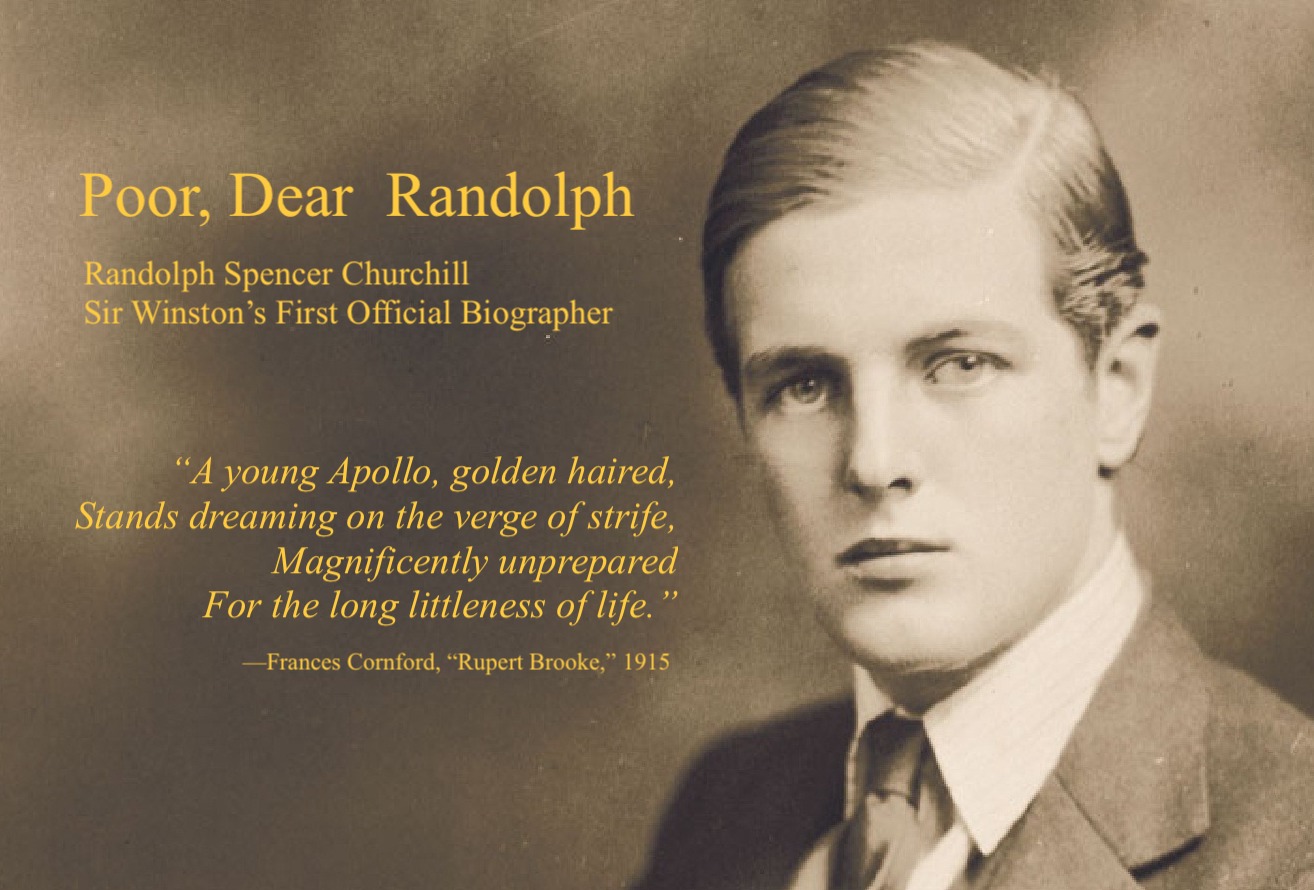

Most everybody has an inkling of who Winston Churchill was. But how many know of his son Randolph? How many British schoolchildren do you think have heard of him? Do they know that Arthur Conan Doyle created Sherlock Holmes, who some think was a real person? They should, Sir Arthur was a great writer. Like Randolph Churchill, who founded the longest biography ever written. In the words of Dean Acheson, he was “present at the creation.”

In his autobiography Randolph wrote, “I was born in London on 18 May 1911 at 33 Eccleston Square, of poor but honest parents. Born within sound of Bow Bells, I was a Cockney and, until I was forty, was destined to spend more than half my life in London.”

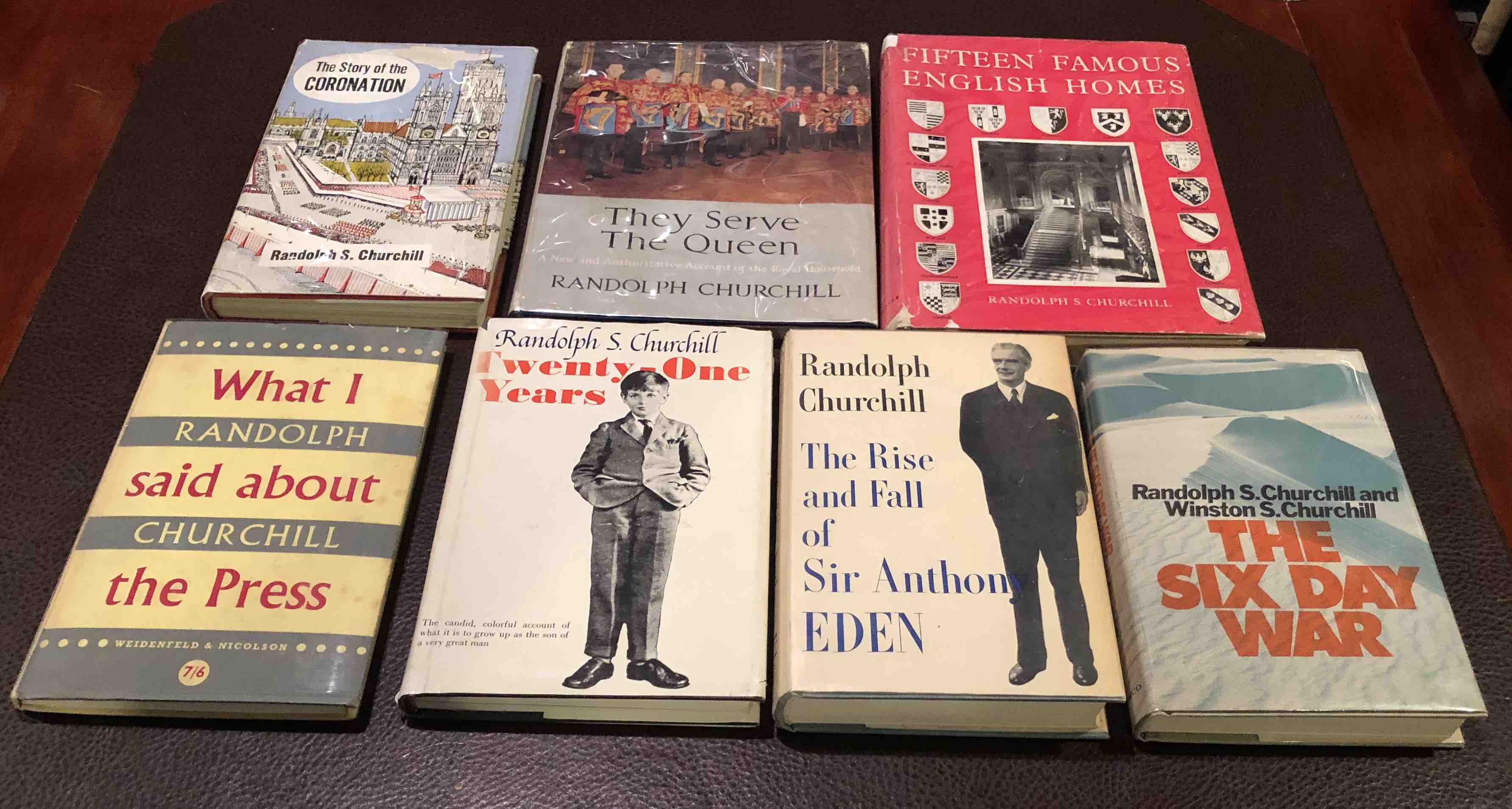

He was written off recently as “a violent drunk marred by scandals, divorces and infirmity of purpose.” In 1953 he was called a “paid hack.” He sued for libel, won, and published a book about it, What I Said about the Press. What he said about the press is interesting. He said they all had the same opinions, mouthed the same lines, and never criticized each other, because as he put it, “Dog don’t eat dog.” Does that sound familiar?

Randolph Churchill as writer

Paid hack and infirmity of purpose are not charges that stick. Randolph’s career in journalism lasted thirty-six years. He wrote hundreds of articles, edited seven volumes of his father’s speeches, and published fifteen books, including the first seven narrative and document volumes of Winston S. Churchill, the official biography.

Paid hack and infirmity of purpose are not charges that stick. Randolph’s career in journalism lasted thirty-six years. He wrote hundreds of articles, edited seven volumes of his father’s speeches, and published fifteen books, including the first seven narrative and document volumes of Winston S. Churchill, the official biography.

After the cruise, we celebrated Hillsdale College’s completion of what Randolph began long ago. He always called it “The Great Work.” If he were here, he would ask, “What took you so long?”

Randolph planned five narrative and perhaps ten document (“companion”) volumes. Sir Martin Gilbert, who joined his staff in 1962 and later succeeded him, found much more material—“lovely grub,” Randolph called it. Sir Martin published eighteen volumes through his death in 2015. Hillsdale College Press began republishing all prior volumes in 2006 and has now added six new document volumes edited by Larry Arnn, who long ago was Martin’s research assistant.

Randolph Churchill was the subject of four books. The first was collection of tributes, The Young Unpretender (The Grand Original in USA), compiled by Kay Halle, the Washington socialite most responsible for advancing Sir Winston’s honorary U.S. citizenship. It’s the kind of book you’d wish your friends would write about you. He is the subject of three biographies. The best is His Father’s Son, by Randolph’s son Winston, in 1996..

Breaking bad

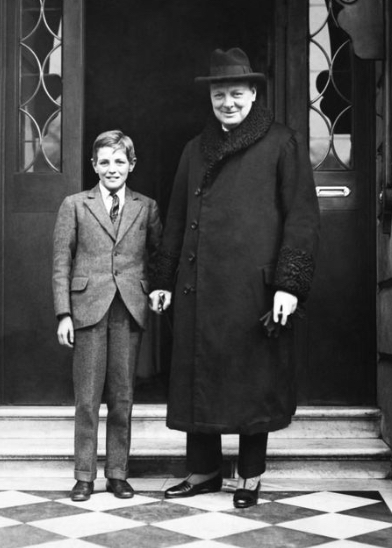

Randolph was what we parents describe as a handful. He went through several nannies, and was troublesome at Sandroyd School in Wiltshire, where he was sent in 1917. At home he was rambunctious. During a visit to Chartwell by Churchill’s friend Bernard “Barney” Baruch, Randolph, aged about 12, positioned a gramophone in an upper story window. As Baruch stepped from his car, Randolph let fly with a recording about a popular cartoon character, “Barney Google, with the Goo-Goo Googly Eyes.”

Baruch laughed, but Randolph’s father stormed up to his room, removed the offending platter, and broke it across his knee.

A friend wrote: “If [Winston] had not been a great man, he would have been a perfect father—building a tree house, helping Randolph with his homework, counseling and encouraging.” Winston spoiled him by inviting him to political dinners with the leading figures of the day. After dinner, Winston would hold up his famous cigar for silence while Randolph held forth.

Randolph thus became a superb extemporaneous speaker, quicker off the cuff than his father. But there was a down-side. He learned to drink hard, in the company of famous cronies like F.E. Smith, Lord Birkenhead. Much to his parents’ consternation, he was drinking double brandies at the age of 18. His father never drank spirits neat, but Randolph never practiced such moderation.

His outspoken, sarcastic and often boorish manner alienated his mother, and their relations were often frosty. Clementine Churchill lived for Winston and Winston was full-time work. Once she reprimanded Randolph for taking a fancy to an older woman. He shot back, “I don’t care…She’s maternal and you’re not.” What few appreciated, his cousin Anita Leslie wrote, was “Randolph’s craving for affection. He had to hide his sensitivity, not realizing either that others could be as sensitive as he.”

“Randolph, Hope and Glory”

At Eton, Randolph wrote, “I was lazy and unsuccessful…and unpopular.” At Oxford in 1929, he took little interest in studies. His father warned: “Your idle and lazy life is very offensive to me. You appear to be leading a perfectly useless existence…. do not value or profit by the opportunities Oxford offers…. You add an insolence toward men and things which is rapidly affecting your position outside Oxford and is certainly not sustained by effort or achievement.” This is a remarkable parallel to the demoralizing letter Winston’s father wrote him around the same age, warning that he was in danger of becoming a “social wastrel.”

Randolph apologized, promised to do better, and campaigned for his father in the May 1929 election. The Conservatives lost and Winston began his decade in the political wilderness. That summer Winston, his brother Jack and their sons Randolph and Johnny toured North America. There Randolph met more of the good and the great. Their Hollywood hosts included Charlie Chaplin, William Randolph Hearst and his mistress Marion Davies, Louis B. Mayer and Spencer Tracy.

In October 1930 Randolph quit Oxford and began a lecture tour of America, hoping to recoup his depleted finances. He began writing for the press and was apparently the first British journalist to warn about Hitler in print. In Munich in 1932, he tried to arrange for his father to meet Hitler—size up the enemy, so to speak. But that interesting prospect didn’t come off.

Aiming (very) high

Predicting in print that he would make a fortune and become prime minister, Randolph ran for Parliament as an independent Conservative in Wavertree, Liverpool in 1935. This embarrassed his father, for Randolph split the Tory vote and handed a safe seat to Labour. But Winston rarely let the sun go down upon his wrath, and when Randolph’s idleness ended in lectures, writing and more political campaigns, he lent encouragement.

Randolph was rebuffed twice more before getting in for Preston, Lancashire. Because of the wartime political truce he was unopposed, but in the 1945 election he lost decisively. After the war he was twice beaten by Labour’s Michael Foot, while practicing his father’s celebrated collegiality. The two candidates would fling invective at each other in public, then meet for a drink afterwards. Foot later told Martin Gilbert, “You and I belong to the most exclusive club in London: the friends of Randolph Churchill.”

Lady friends

With his good looks and affection, Randolph had many romances. He almost married Kay Halle, a lifelong friend who never doubted her decision to refuse him. His 1939 marriage to Pamela Digby, later Harriman, was a failure from their wedding night, when Randolph floored her by reading aloud from Gibbon’s Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire. He hoped to produce an heir before the war took him, and in 1940 Pamela gave birth to their only child, duly named Winston.

Few of his lady friends could handle him, but those who did, like Natalie Bevan, the last and greatest love of his life, were indispensable to him. Like Kay Halle, Mrs. Bevan never married him or lived with him, but they were very close in later years. Martin Gilbert wrote: “It was Natalie who, on so many occasions, raised both our spirits and his; or, in raising his, raised ours.”

I well remember the London launch of Martin’s last narrative volume of the official biography, in 1988. There was Natalie Bevan, still beautiful at 79, quietly enjoying Martin’s, and Randolph’s, triumph.

Second World War

World War II found Randolph in North Africa, performing sensitive intelligence assignments with skill and discretion. Like his father he was absolutely fearless. Anxious for combat, he talked his way into Fitzroy Maclean’s British mission to Tito. He parachuted into Nazi-occupied Yugoslavia, where his exploits were heralded.

In 1944 Randolph’s father met Tito in Naples, saying he was sorry he sorry he was too old to land by parachute; otherwise he would have been fighting with Tito’s partisans. Tito replied: “But you have sent us your son.” Tears glittered in Churchill’s eyes. He always declared a “deep animal love” for Randolph, while adding sadly: “every time we meet we seem to have a bloody row.”