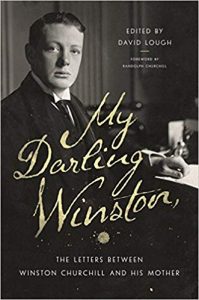

His Mother’s Son: “My Darling Winston,” David Lough, Ed.

David Lough, editor, My Darling Winston: The Letters Between Winston Churchill and His Mother. London: Pegasus, 610 pages, $35, Amazon $33.25, Kindle $15.49. Reprinted from a review for the Hillsdale College Churchill Project. For Hillsdale reviews of Churchill works since 2014, click here. For a list and synopses of books about Churchill since 1905, visit Hillsdale’s annotated bibliography.

See also my tribute to Lee Remick as “Jennie.” and Part 1 of the film.

David Lough…

…added significantly to our knowledge with No More Champagne (2015), his study of Churchill’s finances. Now he fills another gap in the saga with this comprehensive collection of Churchill’s exchanges with his mother Jennie, Lady Randolph Churchill. They range from Winston age seven to the very last letters before Jennie’s death, aged 67, in June 1921.

On the surface it may seem an easy task. Most of the letters are at the Churchill Archives in Cambridge. What could be simpler than digitalizing and publishing the lot? Not so fast. To publish them all would overwhelm the reader, not to mention the publisher. David Lough had to eliminate (or insert ellipses in) many of Winston’s letters from school, for example. This was acceptable, especially for the mandatory weekly “letter home.” Repeatedly those ask for money or parental visits, or offer exaggerated tales of prowess at sport or lessons. Lough offers “a representative but not exhaustive sample.”

On the surface it may seem an easy task. Most of the letters are at the Churchill Archives in Cambridge. What could be simpler than digitalizing and publishing the lot? Not so fast. To publish them all would overwhelm the reader, not to mention the publisher. David Lough had to eliminate (or insert ellipses in) many of Winston’s letters from school, for example. This was acceptable, especially for the mandatory weekly “letter home.” Repeatedly those ask for money or parental visits, or offer exaggerated tales of prowess at sport or lessons. Lough offers “a representative but not exhaustive sample.”

Jennie was much better at keeping Winston’s letters than he hers. As a result, “connecting tissue” is often required from the editor to explain the context. The dearth of Jennie’s letters requires familiarity with her own story. At this Mr. Lough excels, providing us with just enough narrative, without taking over and distracting the reader from his subjects. He also provides excellent maps and uncommon photographs.

“You are in danger of becoming a prig!”

Having David Lough as narrator is like having a skilled tutor guiding us through the four-decade relationship between mother and son. He never falls short. “If we accept that Jennie ‘forgot’ about Winston during his schooldays,” Lough writes, “the ease with which they took up the striking intimacy of their correspondence after Winston left school suggests that she must have forged a stronger bond in his pre-school years than was typical of Victorian parents.” She certainly did—witness her own diaries, and her loyal support of Winston when rebuked by his father. Do well in your grades, she wrote him, and it will eclipse your father’s low view of your prospects. Yet she didn’t hesitate to criticize. Once, finding him adopting a “pompous style,” she warned: “You are in danger of becoming a prig!” For the most part, though, she took joy in his letters.

There are early examples of Churchill’s wry wit and powers of observation. Take Calcutta—please: “A very great city and at night with a grey fog and cold wind—I shall always [be] glad to have seen it—for the same reason Papa gave for being glad to have seen Lisbon—namely ‘that it will be unnecessary ever to see it again.’” On his grandmother Frances, 7th Duchess of Marlborough: “Old age is sufficiently ugly and unpleasing without its too frequent accompaniments, capriciousness and malevolence.” Ouch.

Once commissioned, Winston was desperate for action: “scenes of adventure and excitement,” where he could “gain experience and derive advantage.” He felt hampered in “tedious” India, denied both “the pleasures of peace and the chances of war.” Before long, he was yearning for Crete. Why? Because, Lough explains, he hoped for assignment as a war correspondent during the Greek revolt against Ottoman rule. In a paragraph, Lough explains how this promising fracas was resolved, much to young Winston’s frustration. Yet India would soon provide plenty of war’s chances with the Malakand Field Force. It was the grist for Churchill’s first book.

“Your political career will lead you to big things”

Throughout his letters, notably in his soldier years, we see how Churchill planned his course, always aiming toward politics. “My soldiering prospects are a present very good,” he wrote Jennie from India. “I should continue in the army for two years more. Those two years could not be better spent on active service.” He would ride fame into Parliament. And he did. Politically, his mother’s predictions were more accurate than his. Winston was sure the Conservatives would lose power by 1902, for example. As Jennie expected, they hung on for another four years. Yet, with the sense of timing for which he was renowned, Winston managed to bolt to the Liberals in time for the 1906 election.

Jennie “did nothing to discourage a switch of careers,” David Lough tells us. Indeed his “political ambitions excited her after the premature end of her husband’s ministerial career.” This is exemplary of Lough’s penetrating observations. It is often overlooked that Lord Randolph’s precipitate political fall greatly depressed Jennie, more even than his death. Their son revived her hopes, especially after his hair-raising Boer War adventures: “I am sure you are sick of the war,” she wrote. Now “you will be able to make a decent living out of writings, & your political career will lead you to big things.” She was right again. He was also safer—relatively. In politics you can be killed many times, he later observed; but in war only once.

Separated as they were by oceans and continents, two-thirds of their letters span the years before Churchill entered politics. The rest are largely from early in his political career. There is much more than politics, including details of his romances. He broke up with Pamela Plowden, whom Jennie was sure he would marry, writing his mother in 1901: “We had no painful discussions, but there is no doubt in my mind that she is the only woman I could ever live happily with…” (Not quite.)

Disappointingly, there are no Jennie letters about Lord Randolph’s death. We have no inkling of what she thought: relief, grief, both? Neither will the prurient find the oft-rumored, unsubstantiated, Jennie letters about Clementine Hozier, another woman with whom Winston soon found he could live happily. Jennie had reintroduced them in 1908, after a bad start four years earlier. A long, happy marriage began that year. A fine coda to their early relationship is Winston’s letter to his mother a few days after she ceased being the most important woman in his life: “Clemmy v[er]y happy & beautiful…. You were a great comfort & support to me at a critical time in my emotional development. We have never been so near together so often in a short time.”

“I might have known that 50 miles behind the line was not your particular style…”

Nor do we find revealing letters at critical junctures to come: Churchill’s appointment to the Admiralty, the outbreak of the Great War, his abrupt fall from power. Only after he has resigned to join his regiment do we find him in Jennie’s thoughts again: “I might have known that 50 miles behind the line was not your particular style….It is no use my saying ‘be careful.’ It is all in the hands of God. I can only pray & hope for the best.”

God granted her prayer and he was soon back in the thick of politics. But they never indulged much in political exchanges, as Winston did with Clementine. Jennie’s few letters now were filled with family things: pride in grandchildren, happiness at Winston’s political success, her 1918 marriage to Montagu Porch. His step-father was actually three years younger than Winston, but the marriage worked somehow. Moreover, his mother was happy, and that was what mattered to her son.

This is quite a wonderful collection, shedding bright light on the youthful Churchill’s hopes and dreams, while revealing the worldly, solicitous, loving influence of his American mother. No son could wish for more. For those of us similarly blessed in our lives, David Lough conveys an understanding of why a man is fortunate if he is his mother’s son. As Jennie would write to him often, as our mothers wrote to us: “God bless you my darling and keep you safe.”