Irving Berlin, Isaiah Berlin: Churchill’s Mistaken Identity

Isaiah turned out to be Irving Berlin

My old friend and colleague, John Plumpton in Ontario, writes: “Have you written about Churchill’s confusion over the Berlins when Irving Berlin was invited for dinner? I am looking for an authentic version of the event. Trust you are well and thanks if you can help.”

As it happens the first source I turned up was John himself, writing in “Action This Day,” his “years-ago” column in Finest Hour, which continues under the capable editorship of Michael McMenamin. Here is what I sent John (starting with his own account) about Churchill’s amusing confusion.

John Plumpton, 1994

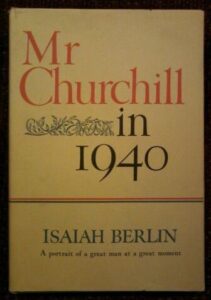

“Churchill had enquired who wrote the political summaries which arrived from the British Embassy in Washington. He was informed that it was Isaiah Berlin, Fellow of All Souls and Tutor of New College. (He subsequently wrote Mr. Churchill in 1940: A Portrait of a Great Man at a Great Moment).

“Churchill had enquired who wrote the political summaries which arrived from the British Embassy in Washington. He was informed that it was Isaiah Berlin, Fellow of All Souls and Tutor of New College. (He subsequently wrote Mr. Churchill in 1940: A Portrait of a Great Man at a Great Moment).“When the famous song writer Irving Berlin arrived to entertain the troops, the Prime Minister confused him with Isaiah and invited him to lunch. Churchill conversed with Irving as if he had been Isaiah, asking such questions as “What do you consider your best work?” Churchill was nonplussed when Berlin told him that it was White Christmas.

The Prime Minister was quite amused later when he learned of the mistaken identity. On meeting the true Isaiah Berlin, Churchill said: ‘I fear that you have learned of the grave solipsism I was so unfortunate to have perpetrated.'” —Finest Hour 82, First Quarter 1994

Rafal Heydel-Mankoo, 1997

John Colville, 1944:

Wednesday, 9 February— Lunched at No. 10 with the P.M. and Mrs. Churchill. The other guests were the Duchess of Buccleuch, Sir Alan and Lady Brooke, James Stuart, mother, Mr. Irving Berlin (the American songwriter and producer), and Juliet Henley. After lunch the P.M. forestalled Irving Berlin asking leading questions by himself addressing them to his potential interlocutor (e.g., “When do you think the war will end, Mr. Berlin?”). This I thought was ingenious technique.

Berlin said he thought Roosevelt would get in at the coming presidential election, and in this his name should help him because in all republican systems human nature triumphed over constitutional principle and the hereditary system came into its own. This also applied to our own Labour Party in which the wife or son of a well known MP was always in demand as a parliamentary candidate.

It later transpired that the reason why Mr. Irving Berlin had been bidden to lunch was a comic misunderstanding. There are sprightly, if somewhat over-vivid, political summaries telegraphed home every week from the Washington Embassy. The PM, inquiring who wrote them, had been told by me, “Mr. I. Berlin, Fellow of All Souls and Tutor of New College.” When Irving Berlin came over here to entertain the troops with his songs, the PM confused him with Isaiah and invited him to lunch—and conversed with him, to his embarrassment, as if he had been Isaiah. —Colville Diary

Jack Fishman, 1963

To be a Churchill luncheon or dinner guest is, very understandably, a much coveted honour. One famous American who can claim to have achieved this distinction is Mr. Irving Berlin. How he did it is a story worthy of one of his own musical comedies.

It happened that in the British Embassy in Washington worked a Mr. I. Berlin, whose regular appraisals of the American scene, sent on to the Foreign Office and subsequently passed to the Prime Minister, were much admired by Winston. He conceived the greatest respect for Mr. Berlin’s wit and political shrewdness.

One morning, in the course of his routine reading of all the newspapers, he noticed that a Mr. Irving Berlin had arrived in Britain from the United States. Having instructed a secretary to make the necessary contact, he informed Clementine: “We shall be having Mr. Berlin to lunch today.” He was too occupied with weightier matters to explain why.

Irving Berlin arrived, to be greeted by Clementine, and even more warmly by Winston. “You have written some wonderful things,” said the Prime Minister. “As you know, I have admired them greatly. Now what, of all that you wrote, do you consider was the best?”

“Well, Mr. Prime Minister,” said Irving Berlin, “I hardly know, but I guess I would say My Heart Stood Still.” [Reader note: A different version of what Berlin named; see note below.]

Winston laughed appreciatively at this apparent piece of wit.

“What’s going to happen in the Presidential election?” he inquired.

“Well, sir,” said Irving, “a lot of people think that Roosevelt will lose.”

“Do they?” said Winston.

“But on the other hand,” Irving continued, “a lot of people think Roosevelt will win.”

* * *

Winston stared at his guest long and hard. Then, suddenly excusing himself, he left the room. “Will you tell me,” he asked a secretary, “whom I am lunching with?”

“Yes, sir. Irving Berlin, the famous American songwriter.”

Clementine looked at Winston as he re-entered the room, trying to fathom his table conversation and his general behaviour. There was no more talk of politics when Winston resumed his seat at the head of the table. He conversed graciously about nothing in particular.

He insisted on joining Clementine in seeing their guest to the door when it was time for him to leave, and expressed the hope that he would come again.

Not until the door closed did he explain the comedy of errors to his puzzled wife. —My Darling Clementine, 88-89.

N.B.

N.B.

There is confusion about which work Irving Berlin told Churchill was his greatest. Since Fishman is the least reliable source among these four and White Christmas such a classic, I buy John Plumpton’s version.

Related content

“Songs Churchill Would Love: Willie McBride” by Eric Bogle, 2017.

“Churchill Anecdotes: Lilli Marlene,” by Hans Liep, 2023.