Garfield, “The Paladin” (or: Christoper Creighton’s Excellent Adventure)

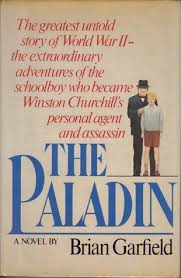

The Paladin, by Brian Garfield. New York: Simon & Schuster, 1979; London, Macmillan 1980; Book Club Associates 1981, several tarnslations, 350 pages. (Review updated 2019.)

Garfield’s gripping novel: fictional biography?

The late, prolific Brian Garfield wrote this book four decades ago, yet I am still asked about it—and whether it could be true.

The story Mr. Garfield tells seems impossible—fantastic. An eleven-year-old boy named Christopher Creighton leaps a garden wall in Kent one day. He finds himself face to face with the Right Honorable Winston Churchill, Member of Parliament. He will later know the great man by the code-name “Tigger.” It is 1935.

Christopher, who continues to invade Chartwell, impresses Churchill with his audacity and pluck. Four years later, aged fifteen, he is recruited into the British Secret Service by a pair of spy-masters known as “Owl” and “Winnie-the-Pooh.”

Christopher’s climacterics

Garfield’s young warrior then accomplishes a succession of what Churchill might call “climacterics.” He warns that Belgium plans to surrender to Hitler. (One book reviewer said “without a fight.”) Advance knowledge of the Belgian collapse enables the British to pull off a fighting retreat, saving 338,000 French and English soldiers at Dunkirk.

But Christopher is just getting warmed up. Next, he finds secret U-boat pens in Ireland and blows the Germans’ most strategic cover for Atlantic warfare. Then he sabotages a friendly Dutch submarine and sends its crew to the bottom after it reports the Japanese battle fleet en route to Pearl Harbor. Churchill has concluded the Americans must not be warned—lest it enable them to avoid war. Back in London, Christopher finishes the job by murdering the only cipher clerk who has read the Dutch sub’s message. And she turns out to be one of his lady friends.

He engineers the assassination of Vichy’s treacherous Admiral Darlan, and tips off the Nazis to the Dieppe raid so they will meet it in force, convincing the Americans that it is too soon for a cross-channel invasion. Finally, when the D-Day invasion really is on, he steers the Germans into defending Calais and not Normandy. By which time Christopher Creighton is a good deal older, wiser, sadder and bloodier. But war is a dirty business!

Counter-factuals

The Belgian scenario is quite contrary to history. The Belgians fought bravely against overwhelming odds for several weeks in May 1940. Also, King Leopold issued warnings of his impending surrender in advance. The Germans never had secret U-boat pens in Ireland. (See for example Warren Kimball’s article, “That Neutral Island.” Dieppe was a disaster, but not by plan: Terry Reardon has carefully catalogued the many errors in its planning and execution. (All three of these articles are published by the Hillsdale College Churchill Project.)

Numerous conspiracy theories attend Pearl Harbor. One says Roosevelt knew and let it happen to get Congress to declare war. Another says Churchill knew, and kept the news from Roosevelt, so the Americans would be dragged in. This is simply silly. No American president, especially a lover of the Navy, would allow his country’s military to be so badly damaged. No British prime minister would withhold advance warning. Surely, an alerted American fleet and aircraft would have engaged the Japanese, and war would have happened anyway.

Read for entertainment, however….

But Brian Garfield spun a great yarn. Although the imagination strains over many conspiracies engineered by a boy, The Paladin is gripping, well-written and plausible. The Churchill Garfield describes tallies closely with the best accounts of his contemporaries. The vivid scenes at the “hole in the ground” (Cabinet War Rooms) are painted with authority. Nazi Foreign Minister Joachim von Ribbentrop, the Belgians and French, the British and German agents, are entirely believable. Brian Garfield is as plausible than Len Deighton, as exciting as Ian Fleming. His novel is splendid entertainment, and you should definitely add a copy to your library of tall tales.

Garfield set tongues wagging back in 1980, when promoting his new book. “The hero is a real person,” he wrote. “He is now in his fifties. His name is not Christopher Creighton.”

I’ve often thought that the Churchill novels of Michael Dobbs are so well scripted, so faithful to the real-life characters in them—and that we would not be surprised to see Dobbs’s scenes described as truth by some careless future writer. Well, Brian Garfield had a twenty-year head start on Dobbs, and did him one better. In the 1990s, someone named “Christopher Creighton” surfaced, with a book about a secret raid on Berlin. We report, you decide.

3 thoughts on “Garfield, “The Paladin” (or: Christoper Creighton’s Excellent Adventure)”

Larry Kryske makes a good point. In the film “Darkest Hour” Churchill relied on the people riding the London Underground to prop him up. A totally fictitious scene and, as we know, WSC didn’t need propping up. He was the prod for others.

I think that’s open to question. Churchill himself had doubts (vide his remark to bodyguard Thompson on 10 May 1940: “All I hope is that it is not too late. I am very much afraid it is.” Until his noble fighting speech to the outer cabinet on the 28th, he had to ponder the very prevalent view, typified by Halifax, to seek a away out. Thus, on the 26th: “If we could get out of this jam by giving up Malta and Gibraltar and some African colonies I would jump at it.” (Cabinet Minutes, Confidential Annex, CAB 65/13). So I put down Dobbs’s “prop up” characters as a fiction author’s license. (Both quotes are in my book, Churchill by Himself, page 272.)

I disagree with your view of Michael Dobbs’s Churchill novels. Sure they are accurate with regard to setting. But in his first one, Winston’s War, Churchill needs Guy Burgess to prop him up and to be resolute. In the second, Churchill’s Triumph, WSC needs a German woman emigrant to prop him up. I don’t think Churchill needed anyone to prop him up. Same goes for James Hogan’s novel, Proteus Operation, about modern-day people going back in time in the 1930s to prop up Churchill.

Comments are closed.