Gallipoli Peninsula 1915: Failure is an Orphan

Excerpted from “The World Crisis (5)” on the Gallipoli Peninsula landings, written for the Hillsdale College Churchill Project. For the original article with more images and endnotes, click here. To subscribe to weekly articles from Hillsdale-Churchill, click here, scroll to bottom, and enter your email in the box “Stay in touch with us.” We never spam you and your identity remains a riddle wrapped in a mystery inside an enigma.

Hillsdale Dialogues: The World Crisis

The Hillsdale Dialogues are weekly broadcasts of discussions between Hillsdale College President Larry P. Arnn and commentator Hugh Hewitt. In 2023-24 they discuss Churchill’s The World Crisis, his classic memoir of the First World War. This essay addresses the operations on the Gallipoli Peninsula. To search for all World Crisis essays published to date, click here. For the accompanying audio discussion, refer to World Crisis World Crisis Dialogue 17, Failure at the Dardanelles and Gallipoli —RML

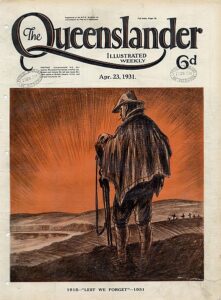

Approaching the 80th Anniversary of D-Day, we may reflect on an earlier seaborne expedition. The attempts to force the Dardanelles, and the opposed landing on Gallipoli, were abject failures. But many lessons were learned, not least by Winston Churchill. Continued from “Dardanelles Straits, 1915.”

Auspicious beginnings

Churchill’s hopes for Greek or Russian troop support had not materialized. Given Asquith’s declaration to “take” the Peninsula, Churchill logically asked whether there should army as well as navy action.

Again the War Minister, Lord Kitchener, insisted that no British land forces be used. Churchill asked for his dissent to be recorded. The Cabinet agreed to a purely naval attack. There was to be a “feint” at the Peninsula, but no actual landings.

The Anglo-French naval force began bombarding the outer forts of the Dardanelles on 19 February 1915. As Churchill expected, those forts were silenced and the entrance cleared of mines in less than a week. Marines landed to destroy the guns at Kum Kale (Asiatic north coast) and Sedd el Bahr (Gallipoli Peninsula), while ships’ guns trained further in toward Kephez.

Some Turkish batteries were mobile. They evaded the fleet’s guns and fired at a motley assortment of minesweepers manned by civilians (a bad mistake by the Admiralty). Still, as late as 4 March Admiral Sackville Carden, commanding, said his fleet would arrive off Constantinople in as little as two weeks.

“Admiral de Row-back”

Shortly after Carden’s optimistic forecast he fell ill, and resigned on March 15th. He was replaced by Admiral John de Robeck, who sailed into the straits on the 18 March. For awhile it was looking good. Eighteen battleships, with cruiser and destroyer support and minesweepers in the van, advanced to midway through the narrowest part of the straits, barely a mile wide. By 2 pm, according to the Turkish General Staff, “artillery fire of the defence had slackened considerably.”

Then misfortune struck. Mines sank the French battleship Bouvet and damaged three older British battleships. Some 650 sailors perished.

Other vessels were damaged, and the civilian minesweeper crews were terrified. Admiral de Robeck, believing he could not sustain further losses, issued a general recall.

Churchill was furious. In his original query to Carden he had emphasized: “Importance of results would justify severe loss.” Angrily he denounced the commander as “Admiral de Row-back.” But First Sea Lord Admiral Lord Fisher supported de Robeck and the fleet was withdrawn. It was never to return.

Peninsula landings

Churchill never gave up his belief that the Dardanelles could have been forced by a renewed attack. But Asquith and the cabinet blinked. Those fervent desk-warriors, once so sanguine about the Dardanelles, were suddenly timid. The naval attack, they decided, must not be renewed without a landing on the Gallipoli Peninsula—which Asquith had targeted without committing troops.

Churchill could not overrule his naval advisors or admirals—let alone Asquith and the Cabinet. Their attention was now on a plan for which Churchill was not responsible: an army assault on the Peninsula.

Landings began at the end of April, ultimately gaining little more than a foothold. In view of the disproportionate numbers often bandied about, the nationality of those brave soldiers needs enumeration. There were over 450,000 British (including Indians and Newfoundlanders) 80,000 French. Added to these were 50,000 Australians and about 15,000 New Zealanders. The Turks mustered 315,000. Casualties and losses were horrific: 250,000 among the Allies, a larger number of Turks.

“Mortal folly done and said”…

General Sir Ian Hamilton, commanding the Peninsula assault, pleaded in vain for Kitchener to send more artillery and better trained, regular army troops.

So many died unnecessarily that Churchill has come in for grave blame, especially in Australia and New Zealand. It is hard to understand this, since did not plan or direct the landing. Almost from the start of the war, he had cast around for ways to avoid using British and Empire ground forces in the Peninsula assault.

Nor was Churchill the sole author and advocate of the naval attack. It had a long genesis, dating back almost to the opening of the war, and was approved by high-level authorities up to Asquith and Kitchener.

Lord Fisher, at first all for the expedition, became increasingly hostile, and finally resigned in mid-May 1915. That cost Churchill his position as First Lord of the Admiralty, as Asquith was now pursuing a coalition government with the Conservatives.

Churchill’s anguished, handwritten letters to Asquith “poured out his inner feelings with intensity, holding back nothing, and risking the derision of the Prime Minister.” But the opposition Tories were adamant. The price of coalition was the First Lord’s head.. This became obvious when Asquith callously asked Churchill: “And what are we to do for you?”

The scapegoat

In his political interests Churchill should have resigned after the Cabinet refused to renew the naval attack. A lesser man would have, but resignation wasn’t in his makeup. It is valid to fault Churchill for failing to carry his First Sea Lord with him in advocating a renewed naval effort. But that raises the question of whether bringing back old Admiral Fisher was a good idea in the first place.

From the end of May to 12 November 1915, Churchill held a meaningless sinecure, Chancellor of the Duchy of Lancaster. His only task was the appointment of rural judges. Frustrated over the ongoing fiasco, he resigned in November to join his regiment on the Western Front.

“Like a sea-beast fished up from the depths, or a diver too suddenly hoisted,” he wrote, “my veins threatened to burst from the fall in pressure. I had great anxiety and no means of relieving it; I had vehement convictions and small power to give effect to them.… I was forced to remain a spectator of the tragedy, placed cruelly in a front seat.”

His wife Clementine had a more poignant remembrance: “When he left the Admiralty he thought he was finished.…I thought he would never get over the Dardanelles; I thought he would die of grief.”

Retrospectives and what-ifs

Clement Attlee, who fought on the Peninsula and later headed the 1945 Labour government, said the Dardanelles-Gallipoli operation was “the only imaginative concept of the war.”

Historians have long debated Attlee’s view. Jeffery Wallin, one of the few early authors to take Churchill’s side, argued that the concept was strategically sound and would have worked. When de Robeck broke off his attack, Wallin wrote, the Turkish forts were almost out ammunition.

Critics countered that the Turkish mobile batteries made up for the loss of fixed cannon, citing their efficiency against the minesweepers. But still others question how much ammunition even the mobile batteries had left. The minesweepers assigned were insufficient, and should not have been crewed by civilians. That detail mistake was the Admiralty’s, thus ultimately Churchill’s.

A further question which has never been answered is: What would have been the effect of the Allied fleet appearing, with guns trained, off Constantinople? Would Turkey have surrendered, as the British thought?

Christopher Harmon wrote that “few analysts, then or now, with the benefit of long hindsight, commit themselves to that assurance. Lord Kitchener, in charge of the War Office, and Churchill, in charge of the Royal Navy, both said at various times that ships alone could suffice. But at other times, each thought otherwise.”

Failures of high command

The record suggests that the immediate failures of the Dardanelles and Gallipoli were owed to gross errors by the commanders. De Robeck was wrong to break off the attack with fourteen of his eighteen battleships intact and some about to pass through the narrows. Hamilton was faulted for landing troops on the Peninsula with uncertain objectives. Professor Harmon summarizes:

Churchill correctly understood the futility of further offensives in the West until some new approach or technology could be ready. He was also correct to want to devote the somewhat inactive Royal Navy to this operation; and with or without troops, he suppoted the naval campaign.

But Kitchener, who offered, then withheld, then provided too late, the 29th Division from Egypt, made a shambles of Admiralty plans to transport the unit, and eliminated any chance of sufficient manpower to sweep away the Turks…. He should have seen that nothing was more important than that this new expedition not fail, not embarrass the Allies, and not waste precious lives of trained men.

Inquiry and conclusions

In 1917 a Commission of Inquiry into the Dardanelles and Gallipoli operations issued its preliminary report. Churchill, it concluded, was “carried away by his sanguine temperament and his firm belief in the success of the operation.” But its main criticism was of Asquith. The Prime Minister had held no War Council meetings from 19 March to 14 May. He fostered an “atmosphere of vagueness and want of precision.

Kitchener “did not sufficiently avail himself of the services of his General Staff, with the result that more work was undertaken by him than was possible for one man to do, and confusion and want of efficiency resulted.” Perhaps Kitchener might not have escaped so lightly, but he had become a martyr, drowning on his way to Russia in June 1916.

What a story! A prime minister unwilling to be prime; a war minister reluctant to make war; backbiting among colleagues; idle babble to outsiders and the press; daily changes of tune; dreaming about unrealistic spoils of war; unwillingness to hear those who understood the real needs.

It doesn’t sound so far removed from the criticism now thrown at Western governments who have inherited the mistakes of a generation, and are expected to mend them overnight.

More on Gallipoli

“Dardanelles Straits, 1915: Success Has a Thousand Fathers,” 2024.

“Get Ready for Churchill’s Anti-Sesquicentennial,” 2024.

“Dardanelles-Gallipoli Centenary,” 2015.

“Churchill’s Potent Political Nicknames: Admiral De Row-Back to Wuthering Height,” 2020.

Keara Gentry, “Lessons of the Dardanelles and Gallipoli,” Hillsdale College, 2024.