Dardanelles Straits 1915: Success Has a Thousand Fathers

Excerpted from “The World Crisis (4)” on forcing the Dardanelles Straits, written for the Hillsdale College Churchill Project. For the original article with more images and endnotes, click here. To subscribe to weekly articles from Hillsdale-Churchill, click here, scroll to bottom, and enter your email in the box “Stay in touch with us.” We never spam you and your identity remains a riddle wrapped in a mystery inside an enigma.

Hillsdale Dialogues: The World Crisis

The Hillsdale Dialogues are weekly broadcasts of discussions between Hillsdale College President Larry P. Arnn and commentator Hugh Hewitt. In 2023-24 they discuss Churchill’s The World Crisis, his classic memoir of the First World War. This essay addresses the question of who conceived and supported the attack on the Dardanelles. The answers still surprise some people. To search for all World Crisis essays published to date, click here. For the accompanying audio discussion, refer to World Crisis Dialogue 16, Turkey and the War —RML

Churchill and the Straits

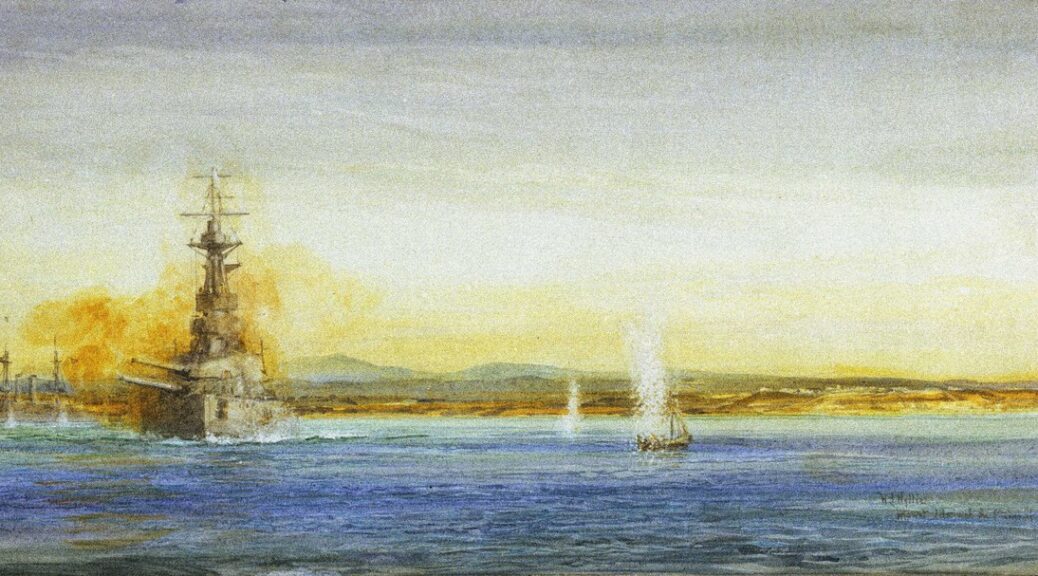

Approaching the 80th Anniversary of D-Day, we may reflect on an earlier seaborne expedition. The attempts to force the Dardanelles, and the opposed landing on Gallipoli, were abject failures. But many lessons were learned, not least by Winston Churchill.

The Allied attempt to force the Straits, and subsequently to land on Turkey’s Gallipoli Peninsula, was a tale of military and political failure at the highest level. It offers timeless examples of hypocrisy, skewed logic, wishful thinking and disloyalty. Winston Churchill observed that such problems often assail countries at war. Yet many historical accounts fix most of the blame on him.

Asquith, Fisher and Kitchener

Over a century later, we may wonder why Prime Minister H.H. Asquith wasn’t pushed aside sooner. Britain, then the superpower among nations, was fighting for survival. At crucial cabinet meetings, Asquith rarely opened his mouth. For almost two months he didn’t hold a war council. Privately he exchanged gossip with his lady friend Venetia Stanley. Most of what we know about his opinions at that time we know through their letters.

In cabinet, Asquith encouraged Churchill; behind his back he doubted and disparaged him. Nor was Lloyd George above criticizing the friend he had mentored. One of Churchill’s civil commissioners, Sir Francis Hopwood, carried slander to the King’s private secretary.

Churchill’s First Sea Lord, Admiral Fisher, military head of the navy, owed his prominence to Churchill. He threatened to resign every time he failed to get his way, and ultimately did so, abandoning his post.

Above all stood Lord Kitchener, Minister of War, enthusiastic for action but unwilling for a time to commit troops when they were first asked for. Vain and unyielding, Kitchener held a veto even over decisions of the Prime Minister. Yet all these people initially backed the Dardanelles naval operation—without reservation.

Getting around the slaughter

It is widely believed that Churchill proposed the Straits expedition to bypass the static slaughter in Europe’s trenches. While this is true in the abstract, the original plan was not his, nor was it hatched overnight.

Churchill and others first contemplated assaulting Germany and Austria-Hungary from the south. Churchill also proposed attacking Germany from the north, even as the Dardanelles operation was being approved by the War Cabinet.

By autumn 1914, Turkey seemed likely to join Central Powers, making Greece a potential British ally. Foreseeing this, Churchill offered the Royal Navy to support a Greek offensive against the Turks. On 4 September he cabled Captain Mark Kerr, on loan to the Greeks to command their navy, authorizing him to raise this possibility with the Athens government.

“The right and obvious method of attacking Turkey,” Churchill wrote Kerr, “is to strike immediately at the heart.” Churchill thought the Greeks could occupy the Gallipoli Peninsula by land, while an Anglo-Greek fleet forced the Dardanelles. This would link up with the Russians via the Bosphorus and Black Sea.

If the Greek plan didn’t work, Churchill offered an alternative: an invasion by Russian troops of European Turkey. Russian casualties might be heavy, but such an enterprise would mean “no more war with Turkey.” At this point he made no mention of British troops.

Hesitation and naïveté

No action was taken on Churchill’s ideas. Then, at the end of September, the Turks mined the Dardanelles, cutting off the Russians from their ice-free link to the Mediterranean. This focused fresh attention on the strategic waterway.

“British military supplies could no longer reach Russia except by the hazardous northern route to Archangel,” Martin Gilbert wrote. “Russian wheat, on which the Tsarist Exchequer depended for so much of its overseas income—and arms purchases—could no longer be exported to its world markets.”

On October 28th, Turkey formally joined the Central Powers. Two days later, Turkish warships began shelling Russian Black Sea ports. The British cabinet fretted over the effect on Russia, and whether the Turks might also attack Egypt.

Asquith wrote to Venetia Stanley: “Few things would give me greater pleasure than to see the Turkish Empire finally disappear from Europe…. Constantinople [might] become Russian (which I think is its proper destiny) or if that is impossible neutralised and become a free port.” These are certainly examples of vapid imaginings.

Admiral Carden eyes the Dardanelles

With the approval of First Sea Lord Fisher, Churchill ordered the Mediterranean commander Admiral Sackville Carden, “without risking any ships,” to bombard the forts at the Dardanelles entrance, at a safe distance from Turkish guns. Carden was instructed to retire “before fire from the forts becomes effective. Ships’ guns should outrange older guns mounted in the forts.”

Carden did so on November 3rd, reporting that the forts were vulnerable to naval bombardment. No allied ships were damaged. One shell hit the magazine of a fort at Sedd-el-Bahr (Gallipoli side of the Straits) which blew up with the loss of almost all its artillery. It was never repaired—nor did the Turks improve other Dardanelles defenses. They remained short of guns, mines and ammunition.

Genesis of the naval attack

The successful shelling of November 3rd caused many to consider Turkey vulnerable. “Like most other people,” Churchill wrote, “I had held the opinion that the days of forcing the Dardanelles were over.” Carden had demonstrated otherwise. The Admiralty War Group concurred.

Results nearby confirmed these views. In December the Mediterranean port of Alexandretta (now Iskerenderun) surrendered under the guns of a single British cruiser, HMS Doris. The Turks actually assisted in demolishing its defenses.

It seemed, Churchill testified, that “we were not dealing with a thoroughly efficient military power, and that it was quite possible that we could get into parley with them.” Characteristically, Churchill was looking for a chance to talk.

“By ships alone”

On 3 January 1915 Churchill, with Fisher’s approval, asked Carden if he thought the Dardanelles Straits could be forced “by the use of ships alone.” Churchill conceived of using a fleet of older British warships, superfluous to the Grand Fleet in home waters.

WSC added: “Importance of results would justify severe loss.” (Emphasis added.)

Carden replied that while he did not think the Straits could be “rushed,” they might be “forced by extended operations with a large number of ships.”

Critics later said Carden was “a second-rate officer who found himself unexpectedly in a sea command instead of in charge of Malta dockyard.” But Carden was the on-scene commander. One only wishes Churchill was blessed with such clear contemporary vision as his hindsight critics.

Churchill telegraphed again to Carden: “Your view is agreed with by high authorities here. Please telegraph in detail what you think could be done by extended operations, what force would be needed, and how you consider it should be used.”

The enthusiastic Admiral Fisher

It is important to note that Churchill’s top Admiralty commander was then still strongly behind the enterprise. Fisher even proposed to supplement Churchill’s older naval vessels with the new battleship HMS Queen Elizabeth. For practice!

The navy’s latest dreadnought, Queen Elizabeth was the first to mount 15-inch guns. She was about to leave for the Mediterranean for test firings. Why not, Fisher suggested, “use her practice shots on the Dardanelles etc. and the possibilities flowing from it.”

Carden said he would need twelve battleships, three battlecruisers, three light cruisers, a flotilla leader, sixteen destroyers, six submarines, eight seaplanes, twelve minesweepers and twenty other craft. Excepting Queen Elizabeth, all could be older, surplus vessels. All were still fit to fight because Churchill had devoted some of his prewar budget to maintaining them.

Carden proposed to start by bombarding the Turkish forts from a safe distance. Then, preceded by minesweepers, he would sail into the Straits, demolishing shore batteries as he found them. He proposed a feint at Gallipoli (Churchill had suggested this in November)—a bombardment but no landings.

Emerging into the Marmara, Carden would keep the Straits open by patrols in his wake. Weather and morale of the enemy were variables, he added, but he “might do it all in a month about.”

Almost total euphoria

The British War Council met on 13 January 1915. Every member was enthusiastic, Maurice Hankey wrote. They “turned eagerly from the dreary vista of a ‘slogging match’ on the Western Front…. The Navy, in whom everyone had implicit confidence, and whose opportunities so far had been few and far between, was to come into the front line.”

Asquith himself drew up the fateful minute. The War Council agreed to a man. Nobody seemed to notice one curious addition. The Admiralty, Asquith wrote, should “prepare for a naval expedition in February to bombard and take the Gallipoli Peninsula with Constantinople as its objective.”

Unanswered questions

How do you “take” a peninsula without troops? Did Asquith mean for sailors to land and march on Constantinople? In the general ardor, no one asked. All eyes were on sailing through the Straits. A fleet this size, appearing off Constantinople, would surely cow the Turks into surrender.

Churchill alone held out for an alternate: attacking the north German coast. Kitchener said there were no troops for that. (He was always short of troops, except to be slaughtered in Flanders.) Of the strictly naval enterprise he was fully supportive. Fisher did not demur.

The War Council waxed euphoric about the possibilities. Next, what about a naval attack up the Danube, landing at Salonika, and sending a fleet up the Adriatic? Colonial Secretary Lewis Harcourt wrote a paper entitled “The Spoils.” He envisioned the end of the Ottoman Empire and expansion of the British Empire as far as Palestine.

None of these naively optimistic visions were voiced by Winston Churchill.

Next: the Gallipoli landings.

More on the Dardanelles

“Dardanelles-Gallipoli Centenary,” 2015.

“Dardanelles Then, Afghanistan Now: Apples and Oranges,” 2009.

“Churchill’s Potent Political Nicknames: Admiral De Row-Back to Wuthering Height,” 2020.

One thought on “Dardanelles Straits 1915: Success Has a Thousand Fathers”

The Dardanelles remain to history as [one of] Churchill’s biggest faux pas. This article presents the “fog of war” and the role that weak and strong, paranoid and courageous, jealous and confident political and military leaders contribute to the “fog”.

Comments are closed.