In Defense of Churchill (4): Questions and Answers

Text of my Zoom address to the Chartwell Society of Portland, Oregon on 10 May 2021, 81st anniversary of Churchill taking office as Prime Minister. “Questions and Answers” are part of an iTunes audio file. For a copy, please email [email protected].

Questions and Answers (continued from Part 3)

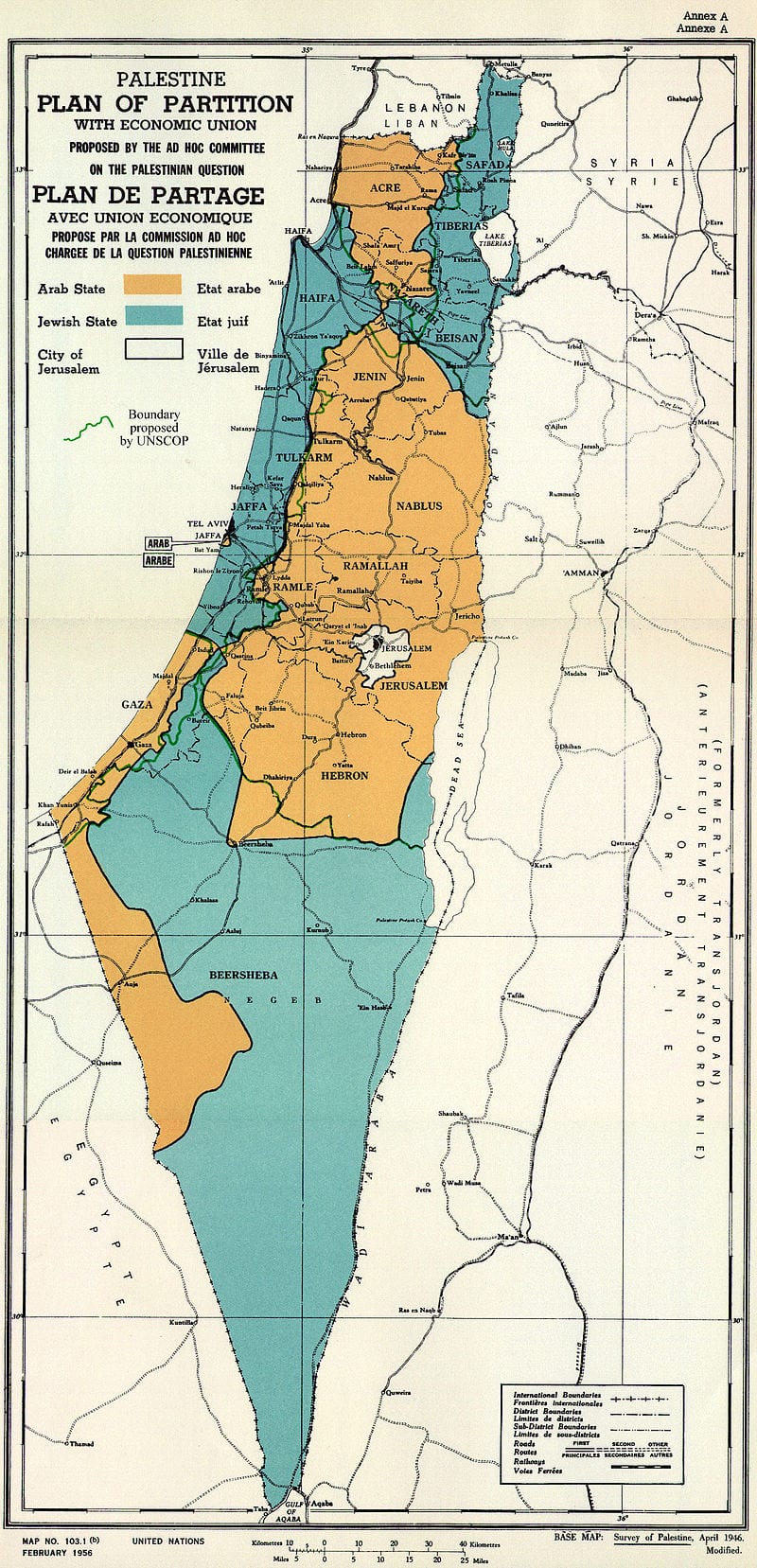

From Senator Bob Packwood (who recalls shelling peas with you on a pleasant former occasion): Everybody asks what Churchill’s position would be today on the Middle East. It appears that he wanted to do right by everybody—guarantee the Jews a homeland but respect the rights of the Arabs. If that view of his is correct. would he be something closer to a pro-Zionist today or a supporter of the PLO? Did Churchill personally support The United Nations partition of Palestine in the 1940s?

Palestine and Israel

Churchill knew the Palestine Mandate (which in 1921 comprised Jordan as well as Israel) posed difficult demographic questions. Yet he was an eternal optimist, less cynical than most. He actually believed, in 1921, that Jews and Arabs could coexist for mutual benefit. That’s why he spoke then of a Jewish homeland, but not a Jewish state. But he did become resigned to the partition, and later the state.

Faced with intransigence, as we have been with the PLO, he always looked for ways to go around the problem—thus the Dardanelles to bypass the stalemate on the western front. But he tended not to support thugs. So I think he would try to go round the PLO by sponsoring Arab treaties of peace with Israel. It is ironic that two U.S. presidents who probably don’t agree on anything else did this successfully: Jimmy Carter in 1978, Donald Trump in 2020.

Here’s what Churchill said in 1958, long after he’d left office:

The Middle East is one of the hardest-hearted areas in the world. It has always been fought over, and peace has only reigned when a major power has established firm influence and shown that it would maintain its will. Your friends must be supported with every vigour and if necessary they must be avenged. Force, or perhaps force and bribery, are the only things that will be respected. It is very sad, but we had all better recognise it. At present our friendship is not valued, and our enmity is not feared.

100 years on?

From Andrew Roberts (who needs no further introduction): Do you think the statue of Winston Churchill will be standing in Parliament Square in 100 years’ time?

Trust Andrew to toss me a spanner! I don’t even know if Parliament will be standing in 100 years’ time. After all, Orwell made London the capital of Oceania in “1984,” remember?

The job of Orwell’s hero, Winston Smith (we know where he got that name) was constantly to rewrite history to suit the party line. Everything proscribed by Big Brother was put into something called the Memory Hole and never heard of again. Statues too, I suppose. The best we can hope for is what Churchill said in 1954:

For myself I am an optimist—it does not seem to be much use being anything else—and I cannot believe that the human race will not find its way through the problems that confront it, although they are separated by a measureless gulf from any they have known before….

If he proves right, Parliament and the statue will endure.

Churchill vs. the Appeasers

Reading Britain At Bay, by Alan Allport, I was struck by just how much hung in the balance early in the war. What personality traits did Churchill possess that made him able to rally a nation and lead so effectively? How were they shaped during his life and how did he draw on them? How do those traits contrast with those of Mr. Chamberlain, whom Allport characterizes as vain, boring, spiteful, friendless, and lacking intellectual curiosity?

There’s a good review of Allport by Professor Raymond Callahan on our website. We also offer an annotated bibliography of works about Churchill. There are now over 1150….18 in 2020 alone.

You have to remember that Chamberlain and many of the appeasers, like Stanley Baldwin, started as businessmen. They had no experience of war, except that it interfered with business. Andrew Roberts makes this point. Hardly any leading appeasers—Chamberlain, Baldwin, Sam Hoare, Horace Wilson, fought in the First World War. (Halifax, who fought with distinction, was the chief exception.) Yet all the leading advocates for defying Hitler were veterans—Churchill, Eden, Macmillan, Louis Spears, Roger Keyes, Alfred Duff Cooper.

Ask yourself why that was. I think those who had fought knew what war would be like. So they wanted to stop Hitler before it came to that. The appeasers thought they could make deals with him, like any other businessman.

When war did come, it required someone with will to see it through. Churchill had that quality. Even Baldwin knew it. I’ll prevent war by accommodating Hitler, he thought, or pit him against the Russians. Baldwin had no place for Churchill in his cabinet. But he also said—and this is a direct quote: “Anything [Winston] undertakes he puts his heart and soul into. If there is going to be war—and no one can say that there is not —we must keep him fresh to be our war Prime Minister.”* That was the difference between them.

*Baldwin to J.C.C. Davidson, quoted in Martin Gilbert, Winston S. Churchill, vol. 5, Prophet of Truth 1922-1939 (Hillsdale, Mich.: Hillsdale College Press, 2009), 687.

“Love me, love my dog”

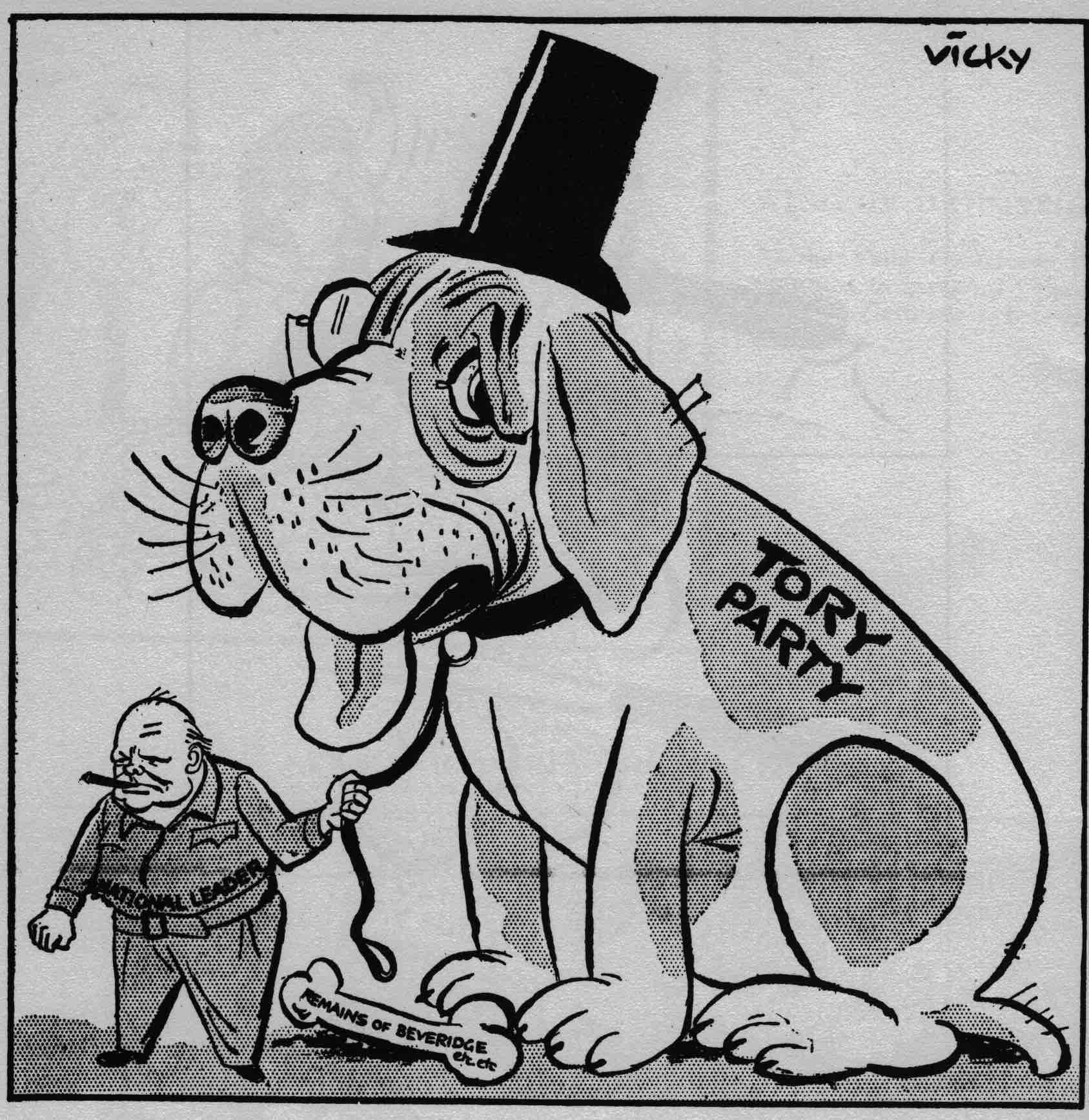

Why did Churchill and his Conservative Party lose the general election and, thus, control of the government, in 1945?

This is among the most frequent questions. Churchill himself didn’t lose. He was reelected by a wider margin than in 1935. His party lost because their history was the war, and the depression before that—and because the Labour Party seemed to promise a brave new world. But after ten years the Conservatives were deeply unpopular.

There’s a funny cartoon showing Churchill before the election, holding the leash to an enormous beagle wearing a top hat, with his tongue hanging out, labeled “Tory Party.” The caption says, “Love me, love my dog.” The voters didn’t love the dog.

Best books

What three books by and about Churchill would you recommend to a new Churchill student? What three books about (not by) Churchill must you take to the Gulag?

That presumes the masters of the Gulag will permit any Churchill books!

This has as many answers as questions, but here’s a try. Among his own books, first read My Early Life. Sure it’s full of inaccuracies and special pleading. But it’s a wonderful read, full of insight into his development.

Then read Marlborough, his greatest biography. In the 1960s it was abridged by Henry Steele Commager, who ruined it. He took out the politics and left only the military. Who cares who won the Battle of Ramillies? In the original you can read all of Churchill’s political philosophy, and see the great war speeches aborning. The scholar Leo Strauss called it “the greatest historical work written in our century, an inexhaustible mine of political wisdom and understanding, which should be required reading for every student of political science.”

Third, The Second World War. Again, it’s biased and one sided, but as he said, “this not history, this is my case.” More important, Churchill describes the war that made us what we are today. So it’s more important than The World Crisis, although The World Crisis is better written. (See “Churchill’s War Accounts: History or Memoirs?“)

About Churchill: I mentioned Andrew Roberts’ Walking with Destiny. Next the Official Biography, because you get to take 31 volumes—you’ll never run out. Third, Mary Soames’s Speaking for Themselves: The Personal Letters of Winston and Clementine Churchill. Because this tells us what they were really thinking—a true revelation of their persona.

“Thou shalt not say…”

What would Churchill do/have done about North Korea’s escalating development of nuclear bombs and missiles, which continues as unabated under the present U.S. administration as it did under the previous one?

This raises the Mary Soames Commandment: “Thou shalt not say what Papa would do about any modern situation. After all, how do you know?” History doesn’t repeat, Mark Twain said, but it sometimes rhymes. I think we can get an idea from Churchill, but not the answer. After all, in 1940 the French fleet posed an existential threat, and he didn’t hesitate to take it out. But the French fleet was not a nuclear arsenal, and France was already defeated. It was not the same situation.

Cancel Culture and Free Speech

What would Churchill’s speech be to the Commons on Cancel Culture and Big Tech Censorship?

I don’t know, but what I’ve said about Cancel Culture is based on his thought. We can learn from it. For instance, in 1933, he spoke about much the same impulses in British life:

The worst difficulties from which we suffer do not come from without. They come from within…. They come from a peculiar type of brainy people always found in our country, who, if they add something to its culture, take much from its strength. Our difficulties come from the mood of unwarrantable self-abasement into which we have been cast by a powerful section of our own intellectuals. They come from the acceptance of defeatist doctrines by a large proportion of our politicians.…Nothing can save England if she will not save herself. If we lose faith in ourselves, in our capacity to guide and govern, if we lose our will to live, then indeed our story is told.

As to censorship, he would say what he said in 1952: “Free speech carries with it the evil of all foolish, unpleasant and venomous things that are said; but on the whole we would rather lump them than do away with it.”

Of course he never met up with social media. That presents a real problem. Umberto Eco said: “Social media gives legions of idiots the right to speak when they once only spoke at a bar after a glass of wine, without harming the community … but now they have the same right to speak as a Nobel Prize winner. It’s the invasion of the idiots.” I don’t know what Churchill would say about that. But he would not censor anybody.

Russia and Ukraine

What do you believe Sir Winston’s view would be today respecting Russia’s military presence on its border with Ukraine? Do you believe he would have perceived parallels with 1937-39 continental Europe?

I take refuge in the Mary Soames Commandment. We cannot say what Papa would do today. We can guess—keeping his principles in mind. He was a great proponent of coalitions, domestic and international. He would want to bring the forces of liberty together on such threats. That suggests what he preached in the 1930s: collective security. Today we have NATO, which he praised. (Do we still have NATO? I think so.) But Ukraine is not part of NATO. So this is the place for inspired diplomacy with nations, NATO or not, whose interests are involved.

Another Churchill?

Is there a Churchill available today? Perhaps in view of your admiration for President Macron?

It’s an incidental admiration, because I don’t admire many of his political ideas. I admire his courage and principle over the statues issue. He was adopting Mark Steyn’s precept: Unless you are prepared to surrender everything, surrender nothing.

I don’t think he’s another Churchill. I don’t see anyone out there who is, really. Do you? Remember too that Churchills only come along when the chips are down. The chips are not quite down, although they seem to be getting there.

2 thoughts on “In Defense of Churchill (4): Questions and Answers”

The Churchill quote you bring nicely addresses the complexities of the Middle East. Perhaps the following statement, to President Eisenhower, reflects Churchill’s personal bias: “I am, of course, a Zionist, and have been ever since the Balfour Declaration.” 295, Churchill and the Jews: A Lifelong Friendship, Martin Gilbert, 2007. Would be delighted to hear your thoughts.

=

I believe he was a Zionist much earlier, but there are probably as many gradients to the meaning of the term as there are political parties in Israel. To Churchill it meant favoring a Jewish National Home, as he called it, as opposed to not favoring one. He was also biased in favor of peaceful solutions—condemning, for example, the Stern Gang assassination of Lord Moyne in Cairo. It is hard to think of him as biased against Arabs, since he parceled off 6/7ths of the Palestine Mandate to what became Jordan. See “Churchill Not a Zionist?” RML

J.M. writes: “You pointed out that the people who advocated stopping Hitler had all fought and seen the horrors of war first hand. On the other side, the appeasers advocated doing everything possible—even giving in to Hitler—to prevent war. This seems a little odd to me. I would have thought it would be the other way around. That is, the people who had seen first hand what war was really like would have been the appeasers while the other faction would have looked upon war as a chance to make money.”

=

That’s a good question. I asked Andrew Roberts, who first made this point in The Holy Fox, his biography of Halifax. Dr. Roberts writes: “The explanation is that having seen the horrors up close snd losing so many friends, they weren’t going to let the Germans win the fruits of a victory they had done so much to deny them last time, without a struggle.”

Alfred Duff Cooper resigned from the Admiralty over Munich, saying it marked the “end of all decency in public affairs.” In his resignation speech he said: “The Prime Minister has believed in addressing Herr Hitler through the language of sweet reasonableness. I have believed that he was more open to the language of the mailed fist.”

Churchill and the anti-Appeasers took this view. Also, having fought them, they weren’t as overawed by the German military as the ex-businessmen. Some may have noticed the way the Wehrmacht clanked into Austria six months before Munich. In the end, Duff and the rest just weren’t content to let the barbarian have whatever he wanted. A lesson we seem to have to learn over and over. RML

Comments are closed.