Winston S. Churchill’s Three Best War Books (Excerpt)

“Three Outstanding War Books” is Excerpted from an essay for the Hillsdale College Churchill Project. Why settle for the excerpt when you can read the whole thing full-strength? Click here.

Better yet, join 60,000 readers of Hillsdale essays by the world’s best Churchill historians by subscribing. You will receive regular notices (“Weekly Winstons”) of new articles as published. Simply visit https://winstonchurchill.

The Question

“What do you think are Churchill’s best books on war? Though he was a great peacemaker, his work there is eclipsed by the climacterics of war. What are his best?”

The River War

In 1885 the Sudan had been overrun by Dervish tribesman under their religious leader, the Mahdi (Muhammad Ahmad). Fourteen years later, London sent Lord Kitchener and an Anglo-Egyptian force (including Churchill) to reestablish sovereignty. Notwithstanding the superiority of British weapons and tactics, the obstacles presented by the Nile, the desert, the climate, cholera and a brave, fanatical Dervish army were formidable.

Churchill excitingly describes the British victory, culminating in the Battle of Omdurman in 1898. Yet he doesn’t hesitate to criticize the actions of his own side. He is particularly critical of Kitchener, whose treatment of the dead Mahdi was shameful, even barbaric. Far from accepting uncritically the superiority of British civilization, Churchill appreciates the longing for liberty among the indigenous Sudanese. But he finds their native regime defective in its disdain for the human rights of its inhabitants.

***

In 1902 for an abridged edition, Churchill excised one-fourth of the narrative, including his criticisms of Kitchener. By then he had entered Parliament, and was wary of burning bridges. He also added some material, so there are two texts: 1899 and 1902. A new and complete edition, prepared by Professor James Muller, containing both the original and 1902 texts has long been developing. It will be linked here when available. (For Dr. Muller’s video presentation at Hillsdale College, “Lessons from The River War, “ click here.)

Uncommonly for a Victorian, Churchill had words of praise for the Muslim warriors, while deploring their savagery toward other Muslims. There are in The River War many examples of Churchill praising Muslims. He considered his Dervish enemies “as brave men as ever walked the earth.” Years later he wrote with deep feeling of Muslim and Hindu soldiers of the Indian Army in the Second World War. Context matters.

For further reflections see Dr. Paul Rahe’s essay, “The Timeless Value of Winston Churchill’s The River War.”

The World Crisis

In 1905 Churchill hired a polymath who was to remain his literary assistant for thirty years. Edward Marsh was a classical scholar, a civil servant and a brilliant litterateur. From that time, Churchill stopped writing his books in longhand and began dictating to teams of secretaries. Marsh vetted the drafts for Churchill’s final approval. They made a marvelous team.

Marsh appears frequently in Churchill’s life. When he died in 1953 Churchill, who seemed to outlive everybody, waxed eloquent: “He was a master of literature and scholarship and a deeply instructed champion of the arts. All his long life was serene, and he left this world, I trust, without a pang, and I am sure without a fear.”

Marsh helped Churchill write The World Crisis, his memoir of World War I. Here Churchill began as First Lord of the Admiralty, fell disastrously from power and volunteered for the front. Then he returned to office as Minister of Munitions. He became Secretary of State for War ironically, just as the war ended. Perhaps not ironically, for the appointment was made by Prime Minister Lloyd George, who nursed a wry sense of humor.

“All about himself”

Whenever I’m asked to recommend a big book by Churchill, I always name The World Crisis. Like all of his war books it is highly personal. One of his friends called it, “Winston’s brilliant autobiography, disguised as a history of the Universe.” One of his enemies said, “Winston has written an enormous book all about himself and calls it The World Crisis.”

A thoughtful critic, Sir Robert Rhodes James, regarded The World Crisis as Churchill’s masterpiece. But he correctly noted that “one can never quite separate Churchill the orator from Churchill the writer.”

Even if you do not read war books you will be entranced by Churchill’s account of the awful, unfolding scene of the First World War. Readers learn of the great power rivalries that caused the war. We observe Churchill’s failed effort to break the deadlock on the Western Front by forcing the Dardanelles, knocking Turkey out of the war. We revisit the carnage of the Somme and Passchendaele. Finally we see Germany almost win and then lost the war in 1918. A fifth and final volume, The Eastern Front, relates the lesser-known horrors of the war in Russia and Austria-Hungary. In his fourth volume, The Aftermath, Churchill covers the decade after victory.

“Are you quite sure? It would be a pity to be wrong”

Two brief excerpts from The World Crisis. The first is a favorite of Colin Powell, who asked me to look it up when he was chairman of the Joint Chiefs. It tells us a lot about Powell, said to be the voice of caution before the 2003 invasion of Iraq.

In 1911, the Germans sent a gunboat to Agadir, Morocco, and almost went to war with France over it. Churchill here describes the exchange of diplomatic telegrams between Berlin, Paris and London as the Agadir Crisis deepened.

They sound so very cautious and correct, these deadly words. Soft, quiet voices purring, courteous, grave, exactly measured phrases in large peaceful rooms. But with less warning cannons had opened fire and nations had been struck down by this same Germany. So now the Admiralty wireless whispers through the ether to the tall masts of ships, and captains pace their decks absorbed in thought. It is nothing…less than nothing. It is too foolish, too fantastic to be thought of in the twentieth century….

No one would do such things. Civilization has climbed above such perils. The interdependence of nations in trade and traffic, the sense of public law, the Hague Convention, Liberal principles, the Labour Party, high finance, Christian charity, common sense have rendered such nightmares impossible. Are you quite sure? It would be a pity to be wrong. Such a mistake could only be made once—once for all.

“The King’s ships were at sea…”

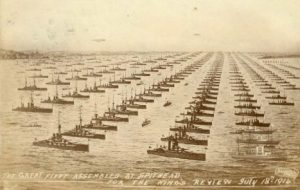

Of course, the mistakes were made, and the world plunged into war, with Churchill running the Royal Navy. In 1914 he did a prescient thing. In July Britain’s Grand Fleet had assembled for a Naval Review. On his own authority, Churchill ordered the Fleet not to disperse. Instead, it sailed in darkness through the English Channel to its war station at Scapa Flow in the Orkneys. Here is Churchill’s description of the passage of the armada:

We may now picture this great Fleet, with its flotillas and cruisers, steaming slowly out of Portland Harbour, squadron by squadron, scores of gigantic castles of steel wending their way across the misty, shining sea, like giants bowed in anxious thought. We may picture them again as darkness fell, eighteen miles of warships running at high speed and in absolute blackness through the narrow Straits, bearing with them into the broad waters of the North the safeguard of considerable affairs….

If war should come no one would know where to look for the British Fleet. Somewhere in that enormous waste of waters to the north of our islands, cruising now this way, now that, shrouded in storms and mists, dwelt this mighty organization. Yet from the Admiralty building we could speak to them at any moment if need arose. The King’s ships were at sea.

One has to look far and wide for writing like that. When he wrote it, our author was 49.

The Second World War

The first book New York Mayor Giuliani read after 9/11 was Churchill’s The Second World War. Anyone who wonders whether Winston Churchill remains relevant today need only consider it.

Consider the major criticisms of Churchill’s most famous work: It is not history. It is filled with grandiose prose, inflicted on an apathetic postwar public who only wanted peace and a quiet life. It is highly biased—the author never puts a foot wrong. He publishes hundreds of his own memoranda and directives, but few replies to them. It moralizes incessantly about dictators and their empires, but not the British Empire. It is vague on the impact of the war on Britain, or the details of Cabinet meetings. Churchill alone seems to confront the French, Hitler, the Soviets, the Americans.

In the words of Arthur Balfour, these complaints contain much that is trite and much that is true. But what’s true is trite, and what’s not trite is not true.

Perhaps one of the best descriptions is by Professor Manfred Weidhorn: “a record of history made rather than written….No other wartime leader in history has given us a work of two million words written only a few years after the events and filled with messages among world potentates which had so recently been heated and secret.”

Humor: his secret of survival

The Second World War is conducted like a symphony, Weidhorn continues—or a first class novel:

Such is the eerie sense of déjà vu and ubi sunt upon his return in 1939, as First Lord [of the Admiralty], to Scapa Flow, exactly a quarter of a century after having, at the start of the other world war, paid the same visit during the same season in the same capacity…. The collapse of the venerable and once mighty France and Churchill’s agony are beautifully rendered by the sensuous detail of the old gentlemen industriously carrying French archives on wheelbarrows to bonfires.

The end finds our hero in Berlin amid its “chaos of ruins.” Churchill walks Hitler’s shattered chancellery for “quite a long time.” The great duel is over; the victor stands where so much evil originated. “We were given the best first-hand accounts available at that time of what had happened in these final scenes.”

“Amid the pathos, humour bubbles,” writes Robert Pilpel. It is “as if Puck had escaped from A Midsummer Night’s Dream and infiltrated Paradise Lost.” There is Churchill’s desert conference with his Generals, “in a tent full of flies and important personages.” There is lunch with King Saud, whose religion forbids tobacco and alcohol—which Churchill says are mandated by his religion. In 1941 he sends a courtly letter to the Japanese Ambassador, signed “Your Obedient Servant.” He announces “with high consideration” that a state of war exists between their countries. (“When you have to kill a man, it costs nothing to be polite.”)

Prudence in statesmanship

What was it, I’ve wondered, that Mayor Giuliani paused over? I’m told he read Volume 2, Their Finest Hour, about Britain in the Blitz. I can only wish today’s leaders, who squabble over inconsequentia as danger mounts, read from Volume 1, The Gathering Storm:

When the situation was manageable it was neglected, and now that it is thoroughly out of hand we apply too late the remedies which might have effected a cure. There is nothing new in the story…. It falls into that long, dismal catalogue of the fruitlessness of experience and the confirmed unteachability of mankind. Want of foresight, unwillingness to act when action would be simple and effective, lack of clear thinking, confusion of counsel until the emergency comes, until self-preservation strikes its jarring gong. These are the features which constitute the endless repetition of history.

How often must we slide slowly down from invincibility, only to be reminded by sudden calamity that we have neglected the primary mission of the state: to provide for the common defense? Churchill wondered. In an unpublished passage for The Gathering Storm he wrote:

Some historians will urge that admiration should be given to a Government of honourable high minded men who bore provocation with exemplary forbearance…. I hope it will also be written how hard all this was upon the ordinary common folk who fill the casualty lists. Under-represented in Government and Parliamentary institutions, they confide their safety to the Ministers of the day.

The Second World War, a prose epic like The River War and The World Crisis, is in the first rank of Churchill’s books. Flaws and all, it is indispensable reading for anyone who seeks a true understanding.

Last thoughts

In the last few years of his life Churchill gave in to the pessimism he had always dodged before. In the late Fifties he told his private secretary, Anthony Montague Browne: “Yes, I have worked very hard and accomplished a great many things—only to accomplish nothing in the end.”

I ventured that Churchill was thinking of the “special relationship” with America, which never reached the closeness he sought. Then too, there was his failure to reach a “settlement” with Russia, although in 1949 he predicted communism would expire. “Yes,” said Sir Anthony, “It was very sad.”

Here anyway are three Churchill books that are must reading: The River War, The World Crisis and The Second World War. They represent an understanding of statesmanship in times of duress. And also, Manfred Weidhorn wrote, “fascinating products of the human spirit.”

They are “epic tales of the depravities, miseries, and glories of man.”

One thought on “Winston S. Churchill’s Three Best War Books (Excerpt)”

Could one make the argument that Marlborough: His Life and Times is a war book? Certainly it centrally presents military history in documenting Marlborough’s considerable achievements. And it does so impeccably well. Writing it also helped to forge the war leader Churchill was to become. To paraphrase from you and others, to understand the charismatic, commanding, defiant, inspiring and tactically bold Churchill of the Second World War, one MUST read Marlborough. David Starkey’s excellent documentary further argues that it was writing Marlborough that reinforced in Churchill the sense of Britain’s—and his own—destiny, sharpened his rhetoric and afforded him the tools with which to overcome the most formidable of foes, Adolf Hitler. So I would suggest that this book, spun round an epic 18th century conflict, qualifies as a war book and, in so doing, takes the gold medal! The World Crisis and The River War take silver and bronze respectively.

–

You are absolutely right that Marlborough is in part a war book, and a great one, probably Churchill’s single best title. But it is also much more than that, as the scholar Leo Strauss often told his students: “The greatest historical work written in our century, an inexhaustible mine of political wisdom and understanding, which should be required reading for every student of political science.” To consider it strictly a war book is what Henry Steele Commager did in 1968, when he controversially abridged the work for Scribners, leaving in most of the soldiering while trimming much of the politics. You are right too that only in Marlboroough can we find the root of the speeches that inspired Britain to stand when she had little else to stand with. It stands, in effect, on a higher rung than his memoirs of the three wars. It is in a class by itself. RML

Comments are closed.